Gabriel García Márquez didn't just wake up one day and decide to write a story about a girl with hair like a copper waterfall. It started with a hole in the ground. Back in 1949, when Gabo was a young reporter in Cartagena, he was sent to cover the emptying of the burial crypts at the Convent of Santa Clara. While the laborers were smashing open the tombs, they found the remains of a young girl named Sierva María de Todos los Ángeles. Her skeleton was unremarkable, but her hair wasn't. It measured twenty-two meters and eleven centimeters long.

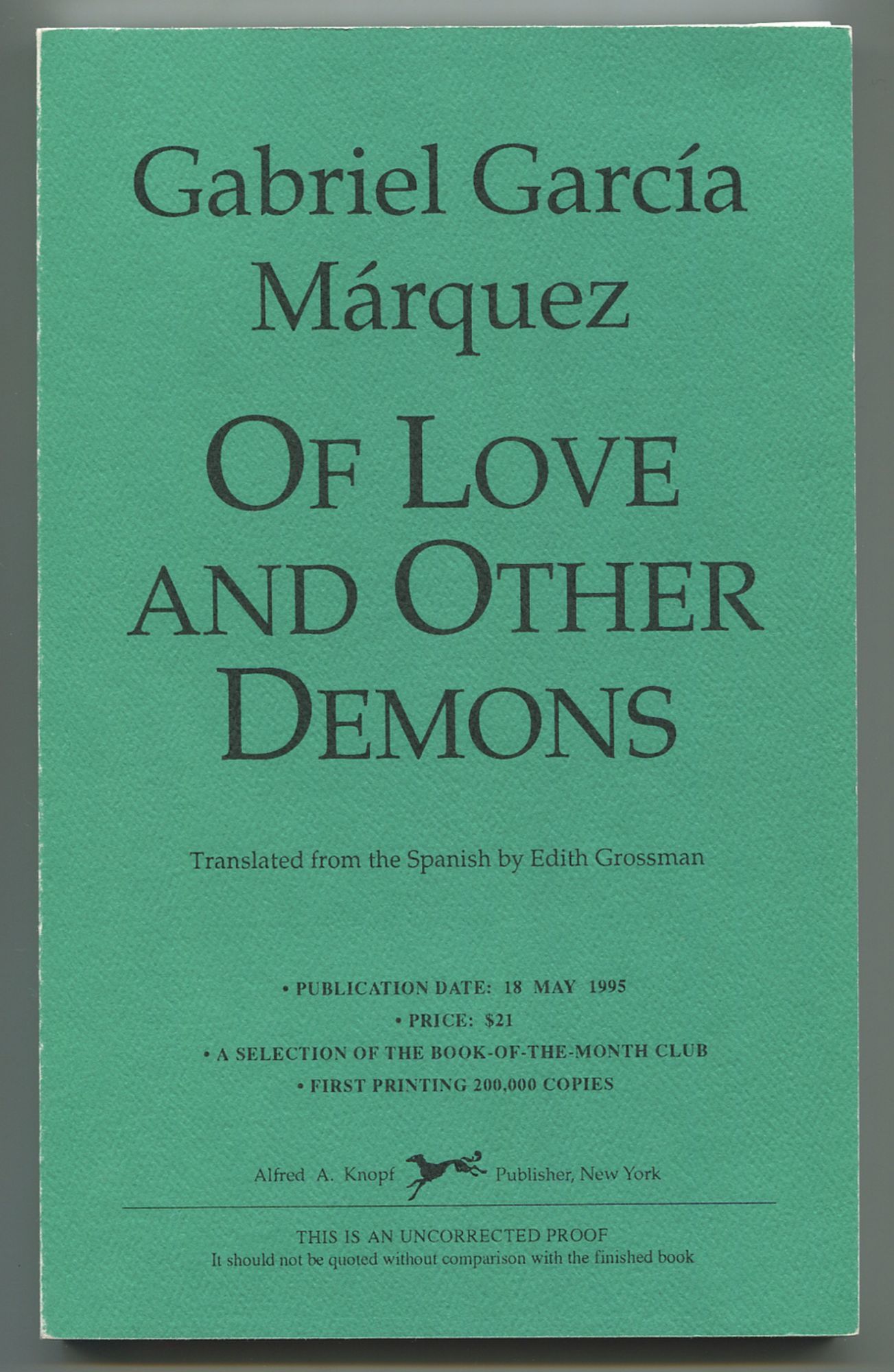

That image stayed with him for decades. Honestly, it’s the kind of thing that would haunt anyone. He eventually turned that journalistic memory into Of Love and Other Demons, a novel that feels less like a book and more like a fever dream. It’s a short read, barely 200 pages, but it packs a heavier punch than many 800-page epics. It tackles the intersection of colonial rot, religious hysteria, and the absolute messiness of human desire. If you think you're getting a romance, you're in for a rough ride.

The Brutal Reality Behind Sierva María

The story follows Sierva María, a twelve-year-old girl born to a useless marquis and a resentful mother. She’s basically raised in the slave quarters of the house. She speaks Yoruba. She dances like the people who actually raised her. She’s an outcast in her own skin. Everything goes south when she gets bitten by a rabid dog in the market.

Now, here is where Márquez gets really sharp. The "demons" in the title aren't literal spirits. They're the superstitions of the Spanish elite and the Catholic Church. Because Sierva María doesn't act like a "proper" Spanish lady, the authorities decide she isn't sick with rabies; she’s possessed. This is the central tragedy. The girl is perfectly fine—or at least, she isn't foaming at the mouth—but the world around her is terrified of what she represents.

I’ve always found it interesting how Gabo treats the Marquis de Casalduero. He’s not a villain in the mustache-twirling sense. He’s just weak. He loves his daughter in a way that is far too late to matter. By the time he hands her over to the Convent of Santa Clara for exorcism, he’s already surrendered his soul to the Bishop. It’s a grim look at how institutional power crushes the individual, especially the vulnerable.

💡 You might also like: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Why Of Love and Other Demons Hits Different in the 21st Century

You might wonder why a book written in 1994 about the 18th century matters now. It matters because we still do this. We still pathologize things we don’t understand. In the book, the "demon" is a stand-in for anything "other"—African culture, female independence, or even just physical illness.

Father Cayetano Delaura is the guy sent to exorcise her. He’s a scholar, a man of books, and someone who thinks he has a handle on his faith. Then he sees her. He falls in love, or at least he falls into an obsession that he calls love. It’s uncomfortable to read. Márquez doesn't give us a "Romeo and Juliet" moment. He gives us a 36-year-old priest losing his mind over a 12-year-old girl who is being tortured by the Inquisition.

It’s messy. It’s supposed to be.

Gabo uses his trademark magical realism, but it’s muted here. The magic isn't in flying carpets; it’s in the impossible length of the hair and the suffocating atmosphere of the convent. The prose is lean. Unlike the sprawling sentences of One Hundred Years of Solitude, Of Love and Other Demons is sharp. It cuts.

📖 Related: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

The Conflict of Belief Systems

There are three distinct worlds colliding in this thin volume:

- The dying Spanish aristocracy, clinging to titles and decaying mansions.

- The Catholic Church, obsessed with sin and the devil.

- The vibrant, resilient culture of the enslaved Africans who actually provide the only warmth Sierva María ever knows.

When Delaura tries to "save" her, he’s trying to bring her into a world that has already rejected her. He recites Garcilaso de la Vega’s poetry to her. It’s beautiful, sure, but it’s useless against the iron bars of a cell and the ignorance of a Bishop who sees the devil in every shadow.

The Symbolism of the Rabid Dog

Let’s talk about that dog. It’s an ash-colored greyhound with a white spot on its forehead. It bites several people, but Sierva María is the one who carries the weight of it. In the medical reality of the time, rabies was a death sentence. But in the narrative reality, the bite is just an excuse.

The dog is a catalyst. It forces the characters to reveal who they actually are. The mother, Bernarda, retreats into her addictions. The father retreats into his guilt. The Church moves in like a predator. It’s a masterclass in how a single event can unravel an entire social structure.

👉 See also: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

What Most Readers Get Wrong

A lot of people try to frame this as a dark romance. That’s a mistake. It’s a critique. If you walk away thinking Delaura is a hero, you’ve missed the point Gabo was making about the destructive nature of colonial obsession. Delaura isn't saving her; he’s just another person consuming her.

The ending is one of the most haunting things in literature. No spoilers here, but it circles back to that journalistic discovery in 1949. It connects the fiction to the bone and hair found in that crypt. It makes the tragedy feel permanent.

Essential Takeaways for Your Next Read

If you’re planning to dive into Of Love and Other Demons, keep a few things in mind to get the most out of it.

- Look at the dates. The story is set in the 1700s, a time when the Enlightenment was happening in Europe, but the Spanish colonies were stuck in a medieval mindset.

- Pay attention to the scents. Márquez is famous for using smells to set a scene—rotting citrus, sea salt, the stench of the convent. It’s a sensory experience.

- Don't expect a happy ending. This isn't that kind of book. It’s a study of how beauty is often destroyed by those who claim to want to protect it.

To really understand the weight of this work, compare it to Márquez's other famous "love" story, Love in the Time of Cholera. Where that book is expansive and somewhat optimistic about the persistence of time, this one is claustrophobic and cynical about the persistence of dogma.

Actionable Next Steps for Readers:

- Read the Foreword: Do not skip the introduction where Márquez explains the 1949 excavation. It provides the factual anchor for the entire narrative.

- Contextualize the Religion: Research the role of the Spanish Inquisition in the Caribbean during the 18th century. It makes the Bishop’s actions much more terrifying when you realize they were based on real historical precedents.

- Cross-Reference with Garcilaso: Look up the poetry of Garcilaso de la Vega. Since Delaura quotes him constantly, knowing the verses adds a layer of irony to his "courtship" of Sierva María.

- Visit the Site: If you ever find yourself in Cartagena, Colombia, you can visit the building that was once the Convent of Santa Clara. It’s now a luxury hotel, which is an irony Gabo probably would have found hilarious and tragic at the same time.