You're standing in front of the rack, staring at the knurling, and wondering if you should sit back or stay upright. Most people treat the front squat box squat debate like it’s a simple choice between "quads" or "glutes." Honestly, it’s a lot more nuanced than that. If you're chasing a bigger total or just trying to keep your knees from exploding, you've got to understand how these two movements interact with your specific anatomy.

The reality is that these lifts aren't competitors. They are specialized tools. One forces you into a brutal upright posture that demands insane core stability, while the other teaches you how to produce massive force from a dead stop. You can't just swap one for the other and expect the same results.

The Front Squat Box Squat Technical Divide

Let’s talk about the front squat first. It’s uncomfortable. There is no way around the fact that having a heavy barbell resting on your deltoids feels like it’s trying to choke you. But that discomfort is exactly why it works. By shifting the center of mass forward, the front squat forces your quads to take the brunt of the load. It’s a quad-dominant monster. Because the bar is in front, if your upper back collapses even an inch, the bar is going on the floor.

Contrast that with the box squat. Popularized largely by Louie Simmons and the crew at Westside Barbell, the box squat is the king of posterior chain development. You aren't just squatting to a box; you’re sitting back, breaking the eccentric-concentric chain, and then exploding upward. It’s a wide-stance movement usually, focusing on the hips, hamstrings, and glutes.

✨ Don't miss: Cocaine: Stimulant or Depressant? Sorting Out the Science and the Myths

Why the Box Changes Everything

When you do a standard squat, you use the "stretch reflex." Think of your muscles like a rubber band that snaps back. The box squat kills that. By pausing on the box—not just tapping it, but actually sitting and releasing the hip flexors while keeping the core tight—you force your body to recruit more motor units to get moving again. It’s pure starting strength.

I've seen lifters with massive back squats get absolutely humbled by a box squat because they've relied on momentum for years. If you can’t get off the box, you’ve got a "static-to-dynamic" weakness. You're basically all snap and no raw power.

Quadriceps versus Posterior Chain Realities

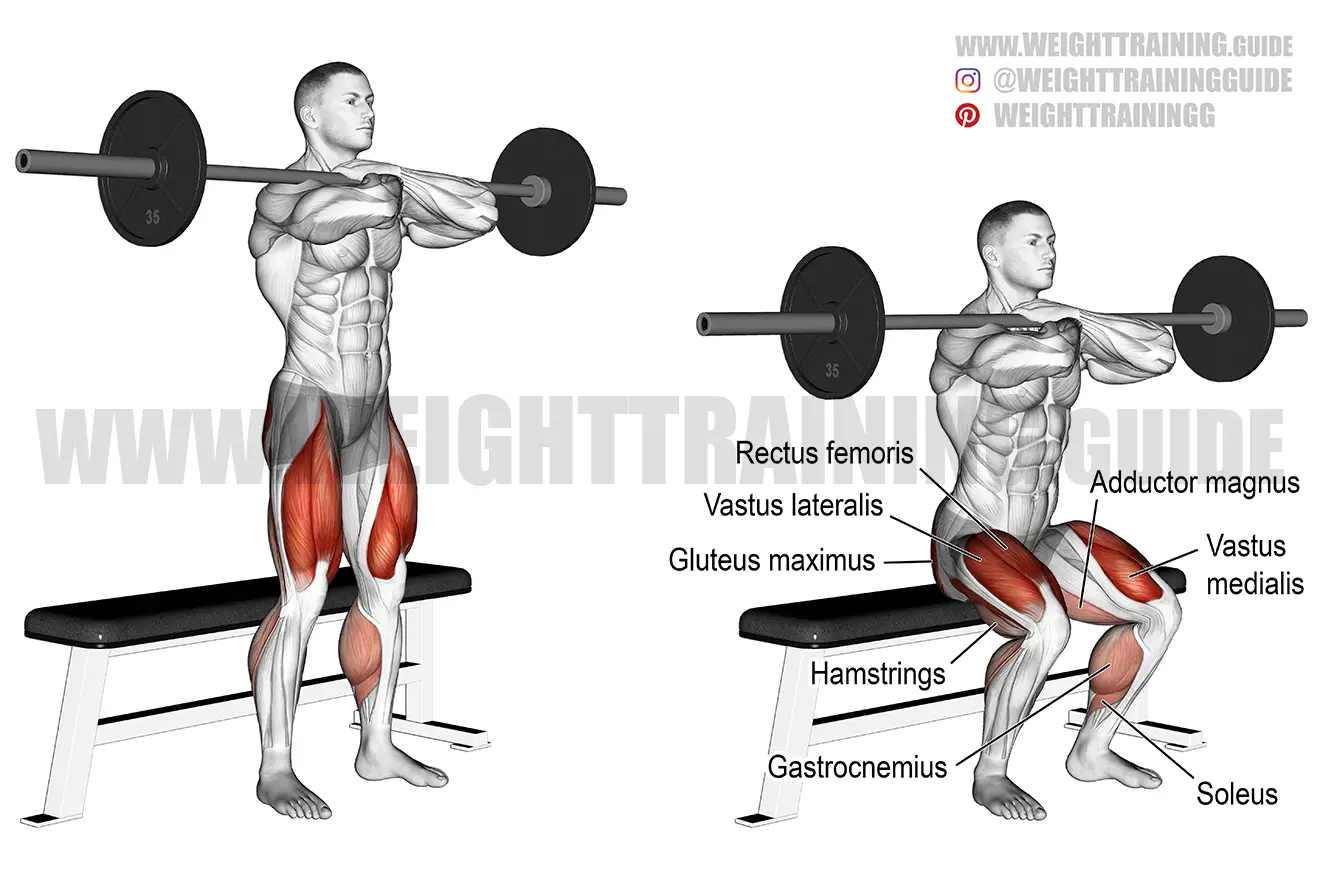

If you look at the EMG data—and there's plenty from guys like Bret Contreras—the front squat consistently shows higher activation in the vastus lateralis and the rectus femoris. It’s a knee-dominant movement. If you have "long levers" (a long femur relative to your torso), the front squat is often your best friend because it allows you to stay more vertical than a traditional back squat ever would.

The box squat, however, is a different beast for your joints. Because your shins stay vertical (or even past vertical) when sitting back onto a box, there is significantly less shear force on the knee. For athletes with patellar tendonitis or general "cranky knees," the box squat is a godsend. You’re moving the stress from the knee joint to the hip joint. Hips are big, beefy, and built to handle that load. Knees are... well, they’re fragile hinges.

The Core Stability Paradox

Everyone says "squats build your core." Sure. But the front squat box squat comparison shows two very different types of stability.

💡 You might also like: Bring Sally Up Challenge: Why This Song Still Kills Your Legs

In the front squat, your erector spinae are working overtime to prevent your thoracic spine from rounding. It’s an anti-flexion battle. If you want a back like a silverback gorilla, front squat. The demand on the anterior core (your abs) is also significantly higher because the weight is trying to pull you forward.

The box squat requires "bracing under duration." You have to hold that internal pressure (the Valsalva maneuver) while you sit, wait, and then drive. If you lose your brace on the box, your spine is going to take a hit the second you try to stand up. It’s a lesson in tension that carries over to every other lift you do.

Which One Should You Program?

Honestly? It depends on your "weak link."

- Case A: You're a powerlifter who struggles with the "hole." You get stuck at the bottom of your squat and your hips shoot up first. Verdict: Box squats. You need to learn to drive from a dead stop and strengthen your glutes to keep your hips under the bar.

- Case B: You're an Olympic weightlifter or a Crossfitter who needs to catch cleans. Verdict: Front squats. You need that upright posture and quad drive to recover from a heavy clean.

- Case C: You just want big legs and have lower back pain. Verdict: Front squats (lower absolute load on the spine) or high-box squats to limit ROM while keeping the shins vertical.

Common Blunders That Kill Progress

Most people treat the box like a trampoline. They bounce off it. If you're bouncing, you aren't box squatting; you're just doing a restricted-range squat with a safety net. You need to come to a complete stop. Your weight should stay on your heels and mid-foot.

On the flip side, the biggest front squat mistake is the "California Grip" (crossing your arms) if you have the mobility to do a full rack. The full rack position—fingertips under the bar, elbows high—creates a much more stable shelf. If your elbows drop, the bar rolls. If the bar rolls, the set is over. If you lack wrist mobility, use straps looped around the bar to create "handles," but for the love of all things holy, keep those elbows up.

Real World Application and Loading

You can't load these the same. Most people can box squat significantly more than they can front squat. Often, a front squat will be about 80% of your back squat, while a box squat might actually exceed your raw back squat if you’re using a wide stance and a suit (though for raw lifters, it’s usually slightly less due to the loss of the stretch reflex).

✨ Don't miss: Mount Sinai Primary & Specialty Care Sunny Isles Beach: What You Should Know Before Your Visit

If you're training for general athleticism, mixing these is smart. I like a 2:1 ratio of front squats to box squats for athletes who need to jump, and the inverse for those who just want to move a house.

Practical Implementation

Don't just throw these in at random.

- Assess your sticking point. Do you fail because your back rounds or because your legs give out?

- Cycle them. Try 4 weeks of heavy box squats (sets of 3-5) to build raw horsepower. Follow that with 4 weeks of front squats (sets of 5-8) to build hypertrophy and postural strength.

- Check your ego. You will lift less weight on a front squat. Accept it. The Carryover to your "big" lifts is what matters, not the number on the bar today.

- Height matters. For box squats, "parallel" is the gold standard, but don't be afraid to go two inches below parallel to build true depth strength, or two inches above to overload the central nervous system.

- Focus on the "Drive." In both lifts, the first inch of movement from the bottom is where the magic happens. In the front squat, drive your elbows up first. In the box squat, drive your traps back into the bar.

Mastering the front squat box squat dynamic isn't about picking a side. It’s about recognizing that your body is a system of levers. Sometimes those levers need a vertical push, and sometimes they need a posterior pull. Stop thinking like a bodybuilder and start thinking like a mechanic. Fix the weak link, and the whole machine runs better.

Focus on your bracing tonight. Tomorrow, pick the lift that scares you the most. Usually, that’s the one you need.