You’re walking down the sidewalk. It’s a normal day. Suddenly, you hit a patch of black ice, and your feet fly out from under you like a cartoon character. In that split second of panic, you’re experiencing a world without enough grip. That’s physics, basically. But if you want the technical answer to what is the definition of friction, you have to look at it as a resistance movement. It’s the force that fights back whenever two surfaces try to slide across each other.

It’s everywhere.

Without it, you couldn’t hold a coffee mug. Your car tires would just spin in place like they’re on a treadmill. Even the air you’re breathing creates a tiny bit of it against your skin as you move.

🔗 Read more: Last Image From Cassini: What Really Happened to Saturn's Lone Explorer

The Nitty-Gritty of How Surfaces Interact

At a microscopic level, nothing is actually smooth. Even a polished glass tabletop looks like a jagged mountain range if you zoom in far enough. When two objects touch, these tiny peaks and valleys—physicists call them "asperities"—interlock and get snagged on each other.

Think of it like trying to rub two pieces of extremely coarse sandpaper together. They don't want to move. To get them sliding, you have to apply enough force to either lift the top layer over the bumps of the bottom layer or literally snap those microscopic mountain peaks off. This interaction is the core of friction. It isn't just one thing; it’s a combination of surface roughness and chemical bonding between atoms. Sometimes, those atoms get so close they actually form temporary "cold welds," sticking to each other for a fraction of a second before being ripped apart by movement.

We usually measure this using the coefficient of friction, which is basically just a ratio. It tells us how "sticky" or "slippery" a relationship between two materials is.

$$f = \mu N$$

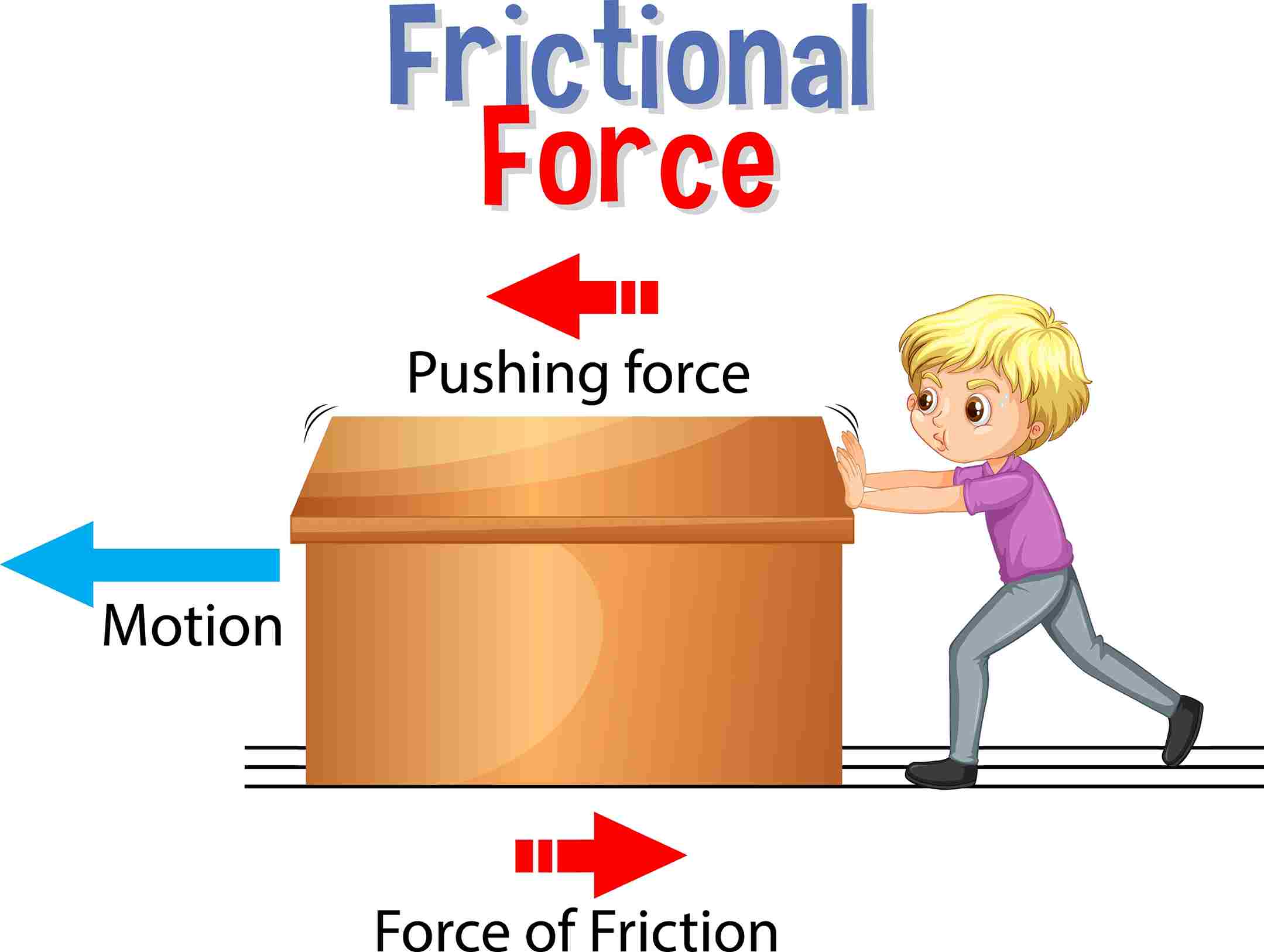

In this equation, $f$ is the force of friction, $\mu$ is that coefficient (the stickiness factor), and $N$ is the normal force—basically how hard the two things are being pressed together. If you push down harder on a box while sliding it, the friction goes up. Simple as that.

Why Static Friction is a Stubborn Beast

Have you ever tried to move a heavy couch? The hardest part is always that first inch. You push and push, face turning red, and nothing happens. Then, finally, it "breaks" free and starts moving.

📖 Related: Cable Box Not Working? How to Fix Your TV Before You Call Tech Support

That initial resistance is static friction.

Static friction is the force that keeps an object at rest. It’s reactive. If you push the couch with 10 pounds of force and it doesn’t move, the static friction is exactly 10 pounds in the opposite direction. If you push with 50 pounds and it still sits there, the friction has scaled up to 50 pounds. It has a limit, though. Once you surpass that "limit of proportionality," the bonds break.

The weird part? Once the object is moving, it actually takes less force to keep it going than it did to start it. This is kinetic friction. Because the surfaces are already gliding, those microscopic "mountain peaks" don't have time to fully settle into the valleys of the other surface. They sort of skip along the top. This is why slamming on your brakes and skidding is actually less effective than "threshold braking" where the tires are still rotating—once you start sliding, you’ve lost that higher grip of static friction.

Fluid Friction and the Invisible Drag

We usually think of friction as two solid things rubbing together, like hands warming up in winter. But fluids—which include both liquids and gases—have their own version.

If you've ever tried to run through waist-deep water, you’ve felt fluid friction. It's thick. It pushes back. In the world of aerodynamics, we call this "drag." When an airplane flies, the air molecules aren't just getting out of the way; they’re rubbing against the wings and fuselage. Engineers spend millions of dollars trying to minimize this by making shapes "streamline."

It’s all about viscosity, really. Honey has high internal friction (it’s viscous), so it flows slowly. Water has low internal friction, so it splashes easily. Even the oil in your car engine is designed specifically to manage friction. It sits between the moving metal parts, replacing harsh solid-on-solid contact with much smoother fluid-on-solid contact. Without that thin layer of lubricant, your engine would heat up and weld itself shut in minutes.

The Good, The Bad, and The Heat

Friction gets a bad rap because it wears things out. It ruins your favorite pair of sneakers and eats away at brake pads. But honestly? We’d be dead without it.

- Fire: Early humans figured out that rubbing two sticks together generates enough heat to start a fire. That’s kinetic energy turning into thermal energy via friction.

- Walking: Your shoes need to "bite" into the ground. On a rainy day, a layer of water gets between your shoe and the pavement, reducing friction and turning your walk into a balancing act.

- Music: A violin bow works because of a "stick-slip" phenomenon. The rosin on the bow hair creates enough friction to grab the string, pull it, and then let it go, creating vibrations.

- Satellites: When a spacecraft re-enters the atmosphere, it’s not just "falling." It’s slamming into air molecules so fast that the friction creates temperatures over 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

There’s also rolling friction, which is what happens with wheels. It’s way weaker than sliding friction, which is why the invention of the wheel was such a big deal. Instead of dragging a heavy stone, you let it roll on logs. You're still dealing with friction where the log touches the ground, but it's much easier to overcome.

Real-World Engineering: Controlling the Grip

In the world of professional racing, like Formula 1, friction is the only thing that matters. Tires are designed to be "sticky." They actually want high friction. These tires are made of soft rubber compounds that essentially melt slightly and mold into the tiny pores of the asphalt. When a commentator talks about "track temperature," they’re talking about how it affects the friction coefficient of the tires.

On the flip side, look at the Maglev trains in Japan. They use magnets to levitate the train above the tracks. Why? To eliminate rolling friction entirely. By removing the physical contact, the only thing the train has to fight is air resistance. This allows them to hit speeds over 370 mph.

What People Get Wrong About Friction

Most people think friction depends on the surface area. It seems logical, right? A bigger box should have more friction than a smaller one of the same weight.

🔗 Read more: Mobile Telephone Numbers UK: What Most People Get Wrong About 07s

Except, it usually doesn't.

Amontons' Second Law of Friction (yep, there are laws for this) states that the force of friction is independent of the apparent area of contact. If you tip a brick on its side or its end, the friction stays the same. Why? Because while the area changes, the pressure changes in the opposite way. A smaller area has more pressure per square inch, squishing those microscopic bumps together harder. It balances out.

Now, this doesn't perfectly apply to soft things like rubber tires—which is why wider tires do help in racing—but for most solid objects, size doesn't matter as much as weight and material.

Managing Friction in Your Daily Life

You’re constantly manipulating friction without thinking about it. You put salt on an icy porch to create a gritty surface (increasing friction). You put WD-40 on a squeaky door hinge (decreasing friction). You wear gloves to get a better grip on a heavy box.

If you’re looking to optimize your own surroundings, consider these moves:

- Check your tires: If the tread is low, you’ve lost the ability to channel water away, which causes "hydroplaning"—a total loss of friction between your car and the road.

- Tool maintenance: If you use garden shears or saws, sap and dirt buildup increases friction, making your muscles work twice as hard. Keep them clean and oiled.

- Ergonomics: Use a mousepad. They are specifically textured to provide just the right amount of "tracking" friction for optical sensors.

- Footwear: If you're a runner, understand that different shoes are "tuned" for different surfaces. Trail shoes have deep lugs to create mechanical friction in dirt, while road shoes focus on surface contact area for pavement.

Understanding friction isn't just about passing a physics test. It’s about realizing that every single movement you make is a negotiation with the surfaces around you. You are constantly pushing against the world, and the world is pushing back. That resistance is what makes movement possible in the first place.

Instead of fighting it, learn where you need it to stick and where you need it to slide. Whether you're seasoning a cast-iron skillet to make it "non-stick" (filling in those microscopic pores with carbonized oil) or chalking your hands at the gym, you're a friction engineer. Act accordingly.