If you walked through the streets of Paris in 1789, you wouldn't just hear the screaming or smell the bread riots. You’d see the walls plastered with paper. Cheap, hand-colored, and incredibly mean. These weren’t "art" in the way we think of the Louvre. A French Revolution political cartoon was a weapon, plain and simple. It was the 18th-century version of a viral meme, but with much higher stakes. If you drew the wrong thing, you didn't just get ratioed on Twitter; you got your head chopped off.

Most people think the Revolution was all about lofty philosophy and guys like Robespierre giving long-winded speeches. Honestly? That’s only half the story. The real revolution happened in the gutters and the print shops. Most of the French population couldn't read Rousseau's The Social Contract. But they could definitely understand a drawing of a fat priest and a wealthy nobleman riding on the back of a starving peasant.

The Three Estates and the Art of the Roast

The social structure of pre-revolutionary France was basically a pyramid scheme. You had the First Estate (the clergy), the Second Estate (the nobility), and the Third Estate (everyone else). About 98% of the people were in that third group, paying all the taxes while the other 2% threw parties.

Artists leaned into this hard. One of the most famous cartoons from 1789 shows an elderly man crawling on all fours, literally carrying a preening count and a bishop on his shoulders. It’s visceral. You don’t need a PhD in political science to feel the unfairness in that image. These prints were produced by the thousands in shops around the Palais-Royal. They were cheap because they used etching or engraving, and they were often colored by hand in assembly lines.

Historians like Lynn Hunt and Robert Darnton have pointed out that these images did something text couldn't: they "desacralized" the monarchy. For centuries, the King was seen as a semi-divine figure chosen by God. A few years of nasty cartoons changed that. Once you’ve seen a drawing of Marie Antoinette as a harpy or Louis XVI as a literal pig, it’s hard to go back to bowing and scraping. The aura of majesty just evaporates.

Why These Drawings Were Gory and Gross

The humor wasn't subtle. It was scatological, violent, and frequently pornographic. If you look at the archives in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, you’ll find images that would make a modern editor blush. Why was it so graphic? Because the revolutionaries wanted to show that the "untouchable" elites were just bodies. Gross, fallible, human bodies.

Take the "Great Rosary of the Third Estate." It’s a series of prints that shows the "patriotic" way to handle enemies of the state. It’s not pretty. The French Revolution political cartoon shifted from being a critique of policy to a demand for blood. By the time 1792 rolled around, the imagery shifted. The "sans-culottes"—the radical working-class partisans—became the heroes. They were depicted as rugged, honest men with pikes, often standing over the defeated remains of the "aristocracy."

The Evolution of the Symbolism

- The Phrygian Cap: That red floppy hat you see everywhere? It was the symbol of a freed slave in Rome. Putting it on a cartoon character was a direct signal of liberation.

- The Guillotine: Eventually, the machine itself became a character. It was called "the national razor." Cartoons showed it "trimming" the excess of the state.

- The National Cockade: Red, white, and blue ribbons. Wearing one in a drawing meant you were a "citoyen." Not wearing one? Well, that was a death sentence in print.

Marie Antoinette: The Favorite Target

If there’s one person who bore the brunt of the propaganda machine, it was Marie Antoinette. The "Austrian woman." The cartoons about her were devastatingly cruel. They accused her of everything from bankrupting the country on diamonds to having affairs with every man (and woman) in the court.

These weren't just "mean girls" behavior. They were calculated political hits. By painting the Queen as a degenerate "other," the revolutionaries made it easier to justify her execution. It’s a dark reminder of how media can be used to dehumanize someone before the physical violence even starts. Scholars like Annie Duprat have researched how these specific images were used to alienate the royal family from the common people. It worked. By 1793, the woman who was once the fashion icon of Europe was being dragged to the scaffold while people cheered.

The Counter-Revolution Fights Back

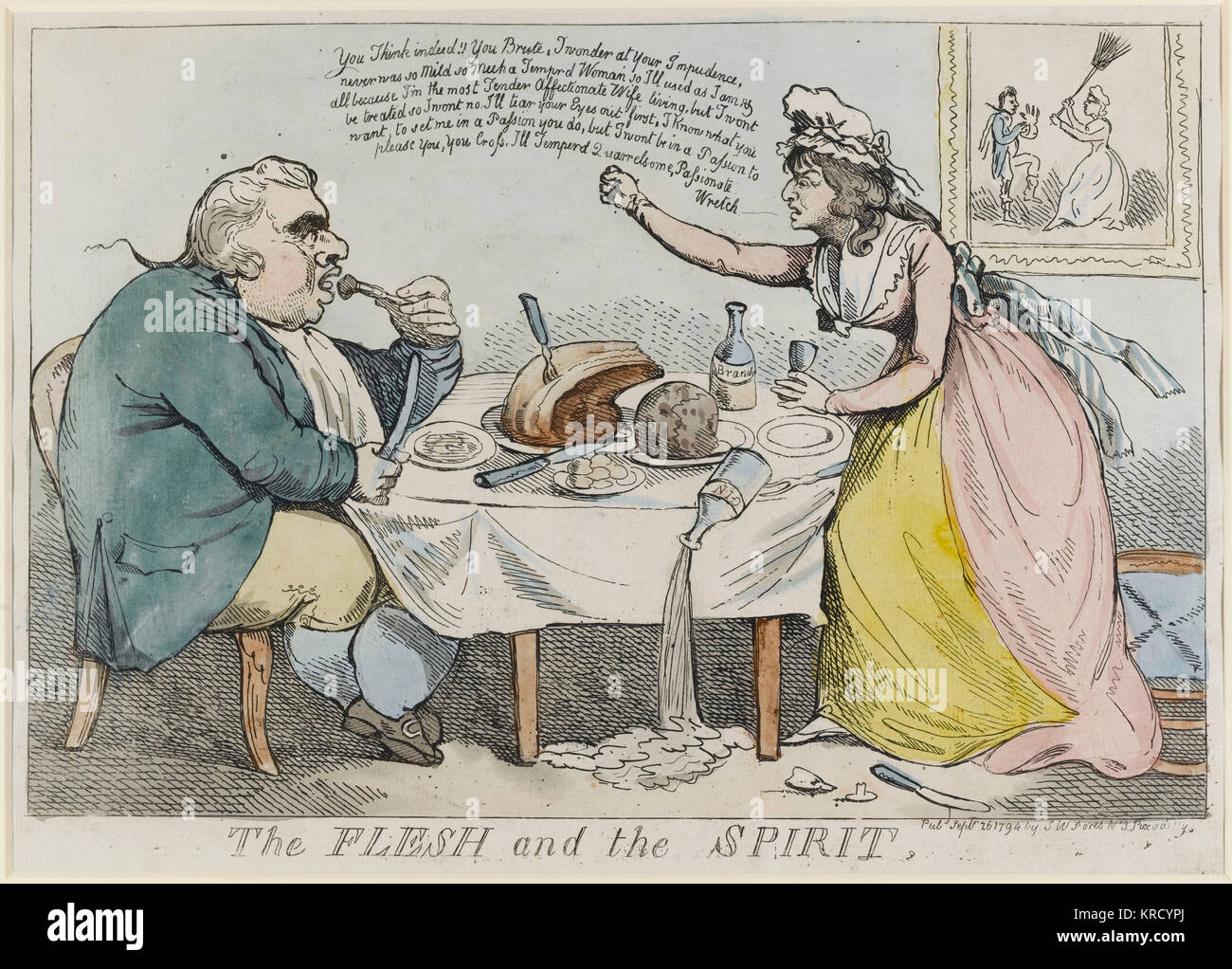

It wasn't a one-way street, though. The Royalists had their own artists. They tried to flip the script by showing the revolutionaries as literal demons or drunken mobs. Some of the most technically impressive cartoons came from English artists like James Gillray.

Gillray was a master of the craft. He sat across the English Channel and drew the French revolutionaries as "sans-culottes" (literally "without breeches") eating human heads or dancing in blood. His work, like The Zenith of French Glory, shows a world turned upside down. To the British, the French Revolution wasn't about "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity." It was about chaos and the breakdown of civilization.

This back-and-forth created a pan-European "war of images." It’s honestly the first time in history we see a truly global media war. Prints were smuggled across borders. They were copied, pirated, and re-captioned in different languages.

👉 See also: Is there a typhoon in Taiwan today? Real-time updates and what you actually need to know

How to Analyze a French Revolution Political Cartoon Yourself

If you’re looking at one of these today, maybe in a museum or an online archive, don't just look at the central figure. Look at the corners. The symbolism is dense.

- Check the lighting. Usually, the "good guys" are bathed in a weird, divine light coming from a "Triangle of Reason."

- Look at the feet. Is someone stepping on a scroll? That scroll usually represents a law or a treaty they're "violating."

- Animal imagery. Is the King a lion? A pig? A helpless sheep? The animal chosen tells you exactly what the artist thought of his power level at that moment.

The colors matter too. Because hand-coloring was expensive, the use of the "tricolor" (red, white, and blue) was a deliberate statement of loyalty to the new Republic. If a cartoon is mostly dark or uses the "fleur-de-lis" (the lily symbol of the monarchy), you’re likely looking at a piece of pro-Royalist propaganda.

The Lasting Impact on Modern Media

You can see the DNA of these 18th-century sketches in every political meme on your phone today. The goal is the same: take a complex, messy political situation and boil it down into one image that makes people feel something. Anger. Superiority. Hope.

The French Revolution political cartoon taught us that images are more "sticky" than text. You might forget a speech, but you won't forget the image of a King's head being held up to a cheering crowd. These artists were the pioneers of psychological warfare. They proved that if you can control the visual narrative, you can topple a throne that has stood for a thousand years.

How to Explore This History Further

If you're actually interested in seeing these for yourself, you don't have to fly to Paris.

- Visit the Digital Archives: The Stanford University Libraries have a massive "French Revolution Digital Archive" where you can zoom in on these prints.

- Check out the British Museum: They have an incredible collection of the satirical prints from the British perspective.

- Read "Citizens" by Simon Schama: He’s a historian who writes like a novelist and pays a ton of attention to the culture and "vibe" of the era, including the art.

- Search for "The Petit Journal": While a bit later, it shows the evolution of French mass-media illustration that started during the Revolution.

To really get a feel for the era, try to find "The Awakening of the Third Estate." It’s a print that shows a member of the commoners breaking his chains while the nobility and clergy recoil in horror. It captures that exact moment where the world shifted. It’s not just a drawing; it’s the sound of an old world breaking.

Next time you see a political meme, just remember—the French were doing it first, they were doing it with more ink, and they were doing it while the guillotine was literally waiting around the corner.

👉 See also: Survivor Stories From 9/11: What We Still Haven’t Learned From Those Who Made It Out

Actionable Insights for Students and History Buffs:

- Look for the "Leveling" motif: Many cartoons show the "Level" (a mason's tool), symbolizing the revolutionary goal of making everyone equal in height—usually by removing heads.

- Identify the "Two-Faced" character: Many prints depict politicians with two faces to show their perceived treachery as they shifted between supporting the King and the Republic.

- Pay attention to the background: Often, the most radical messages are hidden in small details, like a distant building on fire or a specific person hanging from a lamp post (the "lanterne").