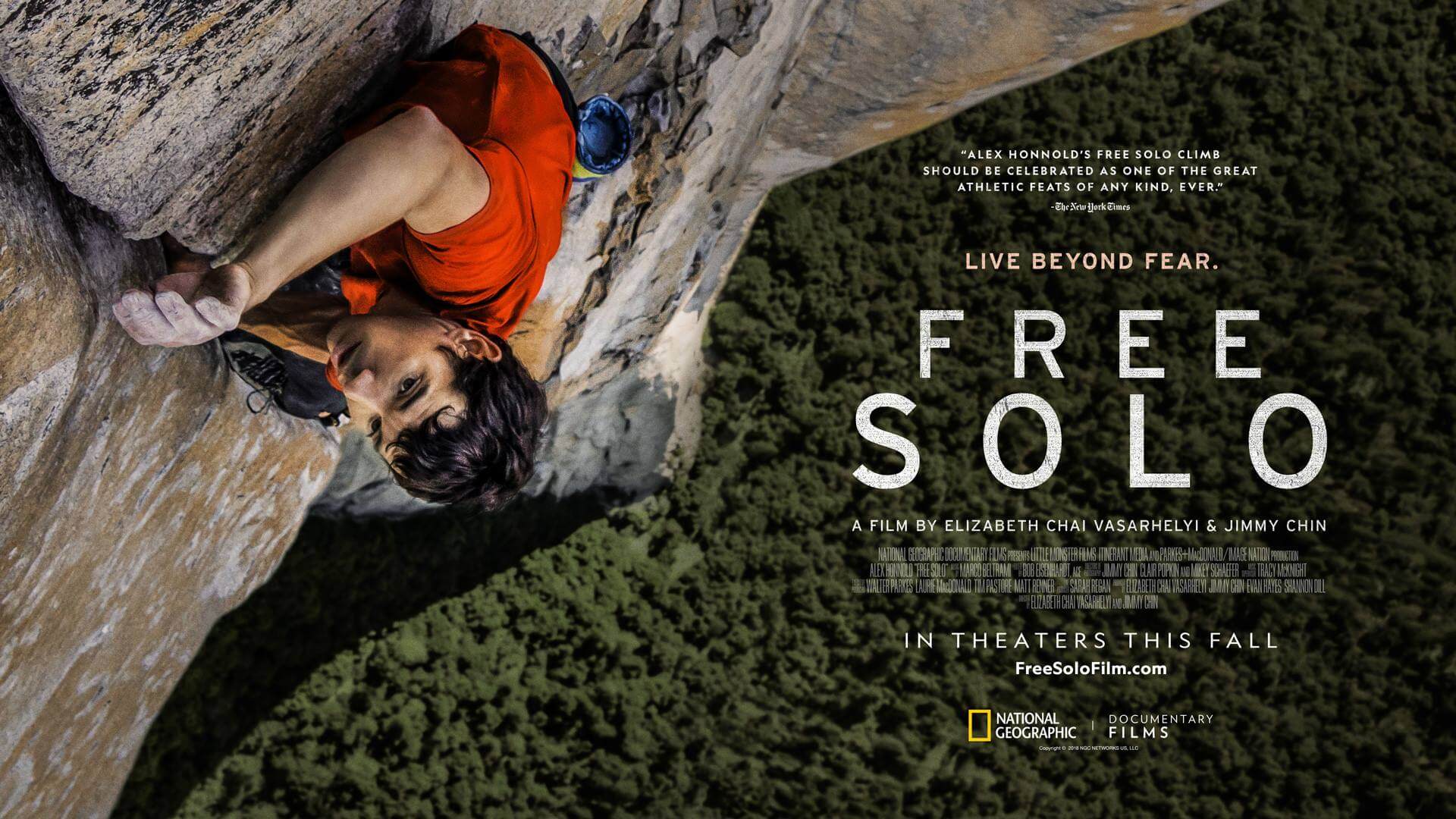

Most people think they understand the gravity of it. They’ve seen the Oscar-winning documentary. They’ve seen the vertigo-inducing wide shots of a tiny human speck against 3,000 feet of sheer granite. But honestly, the actual reality of Alex Honnold’s free solo El Capitan is even weirder and more stressful than the movie makes it out to be.

It isn't just about "not falling."

When you’re standing at the base of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, the wall looks like a physical impossibility. It’s a monolith. It’s the Everest of rock climbing. For decades, the best climbers in the world used hundreds of pounds of gear, bolts, and ropes to reach the top. Then, on June 3, 2017, Honnold walked up to the base with nothing but a pair of sticky rubber shoes and a chalk bag. No backup. No safety net. If his foot slipped a quarter of an inch, he was dead.

That’s the part we struggle to wrap our heads around. It wasn't a stunt. It was the culmination of a decade-long obsession that nearly broke him several times before he even started the climb.

The Freerider Route and Why It’s Terrifying

Free soloing El Capitan isn't just one long ladder climb. Honnold chose the Freerider route, which is a 5.13a graded climb. For non-climbers, that basically means the holds are sometimes no bigger than the edge of a dime. You aren't grabbing onto handles; you're pressing your fingertips against microscopic ripples in the stone and hoping friction holds.

The Freerider has several "cruxes"—the hardest parts of the climb.

First, there’s the Freeblast. It’s a slab section early on where the rock is smooth as glass. You don't "hold" anything here. You just balance. You lean your body weight precisely over your feet and pray the rubber on your shoes bonds with the granite. Honnold actually backed off a previous attempt because the Freeblast felt "too slippery" in his head.

Then comes the Boulder Problem. This is the one everyone remembers from the film. It involves a "karate kick" maneuver. You have to reach your left leg out across a gap to a tiny foothold while your hands are basically useless. If you miss the kick, you’re gone. It’s a move that professional climbers fail on all the time when they have ropes. Honnold had to do it with the certain knowledge that failure meant a 2,000-foot drop.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Risk

People call Alex a "daredevil."

He hates that. To him, daredevils take chances. He spent years removing the chance. He climbed the Freerider over 50 times with ropes. He memorized every single handhold. He knew exactly which finger went where, how much pressure to apply, and where the "greasy" spots were that might get slippery in the sun.

He didn't go up there hoping to survive. He went up there knowing he would.

But even with that preparation, the margin for error is microscopic. Environmental factors are the real killers in the world of free soloing. A bird flies out of a crack and startles you. A piece of granite flakes off—granite is generally solid, but it’s still nature. A sudden gust of wind in the "Hollow Flake" section could theoretically push a climber off balance. This is why many elite climbers, like Tommy Caldwell, were openly terrified for Alex. They knew that no matter how good you are, you can't control the mountain.

The Mental Game: Amygdala and Fear

There was a famous study where neuroscientists put Honnold in an fMRI machine. They showed him gruesome, high-arousal images—things that would make a normal person’s heart race and their amygdala (the brain’s fear center) light up like a Christmas tree.

His amygdala barely twitched.

Some people think he’s a "biological freak" who doesn't feel fear. That's a bit of a simplification. Honnold describes it more like a muscle he’s trained. He feels the fear, but he’s categorized it so deeply that it doesn't translate into physical panic. On free solo El Capitan, panic is the literal death sentence. If your heart rate spikes, your muscles tense. If your muscles tense, you lose the fluid motion needed for "smearing" your shoes against the rock. You start to shake—what climbers call "sewing machine leg."

He climbed for 3 hours and 56 minutes. Think about that. Nearly four hours of absolute, flawless physical execution where a single momentary lapse in focus results in total annihilation.

The Ethical Debate Nobody Talks About

While the world cheered, the climbing community was deeply conflicted.

Free soloing has a dark history. Many of the legends who pioneered the sport are dead. Derek Hersey, John Bachar, Dan Osman—all gone. When Honnold completed his ascent, there was a sense of relief, but also a lingering fear of the "Honnold Effect." Would younger, less experienced climbers try to mimic him for Instagram likes?

Fortunately, El Capitan is its own deterrent. It is so big, so intimidating, and so technically difficult that very few people have the ego to think they can just show up and solo it. It requires a level of mastery that takes decades to build.

The cameras were another issue. Jimmy Chin, the director of Free Solo, struggled with the ethics of filming. If Alex fell while the cameras were rolling, the crew would have essentially participated in a snuff film. They had to hide their faces and look away during the Boulder Problem. The pressure on Alex was immense; not only did he have to climb for his life, but he had to do it while knowing his friends were watching him through long-distance lenses, potentially witnessing his end.

📖 Related: Finding the Real-Time Score to the Auburn Game Right Now

The Gear That Actually Matters

Even though he used no ropes, the gear he did use was specific.

- Shoes: He used La Sportiva TC Pros. These are high-top climbing shoes designed by Tommy Caldwell specifically for the technical granite of Yosemite. They have stiff soles to support the foot on tiny edges.

- Chalk: Friction is everything. He used a standard chalk bag to keep his hands dry. Moisture (sweat) is the enemy of granite climbing.

- The "Tag" Line: In some sections, he actually had to be careful not to get his clothes caught. Everything was streamlined.

Beyond the Achievement: What’s Next?

After the climb, Honnold basically ate some vegan chili in his van and went for a hike. He didn't retire. He didn't stop. But he hasn't tried to "top" El Capitan because, frankly, there isn't much left to top in terms of sheer iconic status.

The feat changed how we view human potential. It proved that the "impossible" is often just a matter of extreme, almost pathological preparation. If you want to understand the spirit of the climb, you have to look past the danger and see the craftsmanship. It was a physical performance as precise as a world-class violinist playing a concerto, just with much higher stakes.

Practical Takeaways for Aspiring Climbers

If you're inspired by the story of free solo El Capitan, don't go out and ditch your rope. Use that inspiration to improve your technical skills.

- Master Your Footwork: Slab climbing in Yosemite is 90% footwork. Practice "smearing" on low-angle rock at your local crag. Trusting your rubber is a skill that takes years to develop.

- Focus on Endurance: Honnold’s ability to stay focused for four hours is what saved him. Long, slow climbs on moderate terrain can help build the mental stamina required for big walls.

- Read the Source Material: Pick up a copy of The Push by Tommy Caldwell or Alone on the Wall by Alex Honnold. These books provide a much deeper dive into the technicalities of the Freerider route and the history of Yosemite climbing.

- Visit Yosemite: You don't have to climb El Cap to appreciate it. Seeing the "Big Wall" from the meadow gives you a perspective that no 4K video ever can. Look for the tiny headlamps of climbers sleeping on portaledges halfway up the face at night.

The legacy of the climb isn't about the risk—it's about the discipline. Alex Honnold didn't conquer the mountain; he conquered his own biology to become a part of it for a few hours. That kind of mastery is available to anyone, regardless of the field, if they're willing to put in the decades of "boring" work that leads to the "extraordinary" moment.