Imagine standing in a packed hall in Rochester, New York, in 1852. The air is thick. It’s hot. You’re there to celebrate the nation’s 76th birthday. Then, a man walks up to the podium. He doesn't start with fireworks or flags. Instead, he asks a question that basically sucks the oxygen out of the room: "What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?"

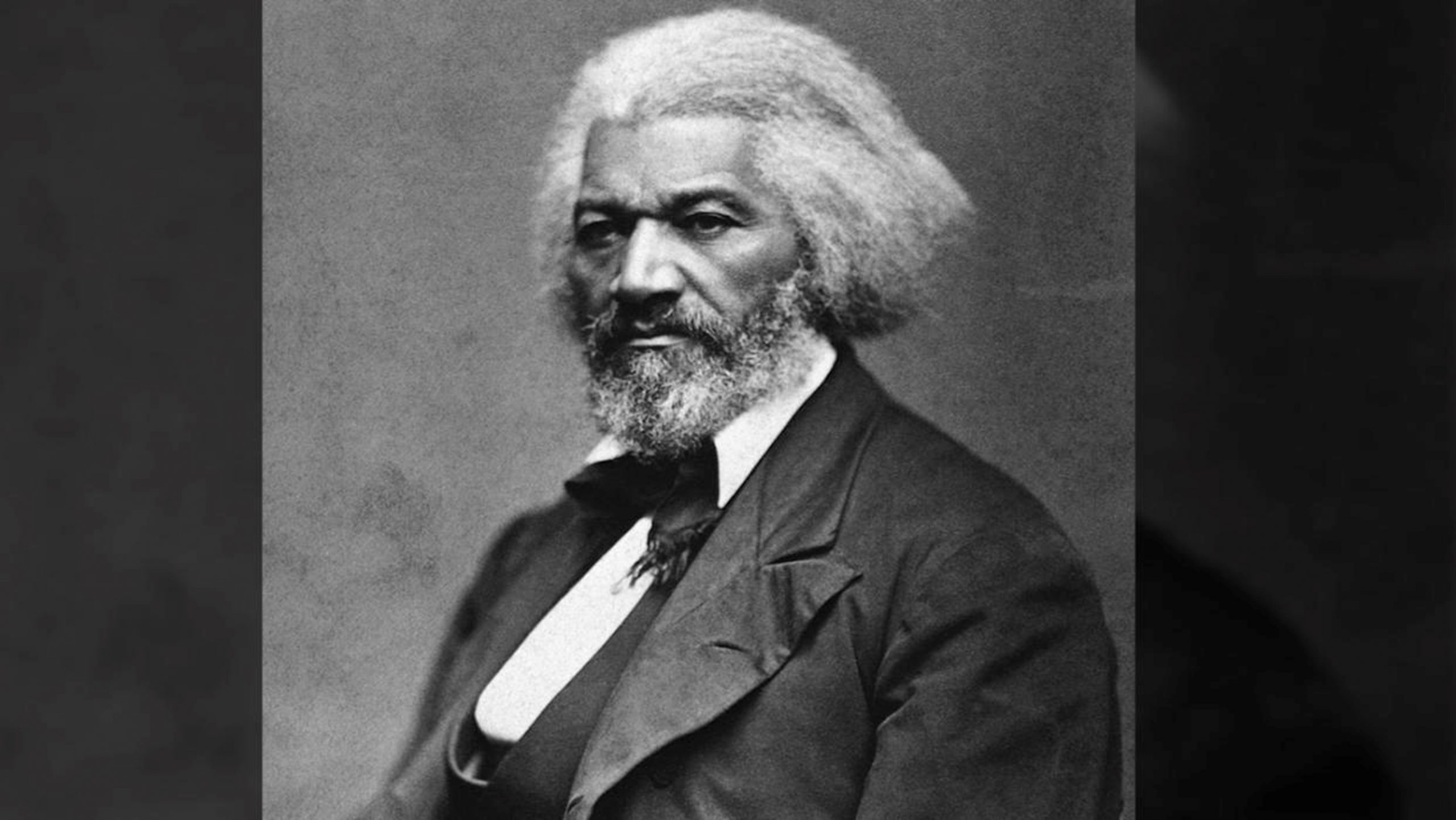

That man was Frederick Douglass. His Frederick Douglass Fourth of July speech—properly titled "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?"—is arguably the most blistering piece of oratory in American history. People today often treat it like a generic patriotic quote on a social media graphic. Honestly? That’s a mistake. This wasn't a "happy birthday America" card. It was a forensic takedown of a country's soul.

The Setup: Why July 5th?

First off, a bit of trivia that usually gets missed: Douglass didn't actually give the speech on July 4th. He gave it on July 5th.

Why? Because for Black Americans in the 1850s, the Fourth was a day of mourning, not celebration. While white families were out shooting off cannons, Black communities often stayed indoors to avoid the "celebratory" violence that tended to spill over into their neighborhoods. By speaking on the 5th, Douglass was already making a point before he even opened his mouth.

He was invited by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. There were about 600 people in Corinthian Hall. Most were sympathetic abolitionists, but Douglass didn't go easy on them. He started with this deep, almost painful humility. He talked about how he "quailed" before them. He called the Founding Fathers "brave men."

It was a total head-fake.

He lured the audience in by agreeing that the Declaration of Independence was a masterpiece. He called it the "ring-bolt" of the nation's destiny. But then, he pivoted. Hard. He moved from "your" fathers to "your" Fourth of July. He made it clear he wasn't included in the "we" of the American experiment.

The Heart of the Frederick Douglass Fourth of July Speech

When Douglass finally answered his own question, he didn't use flowery metaphors. He used a hammer.

🔗 Read more: Security Breach: What Really Happened When Masked Burglars Broke Into Windsor Castle

"I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim."

He called the celebration a sham. He called the nation's "boasted liberty" an unholy license. To Douglass, the sounds of rejoicing were "empty and heartless."

He wasn't just being moody. He was pointing out a literal, legal contradiction. At the time, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was in full effect. This law basically turned the entire North into a hunting ground for slave catchers. Even in "free" New York, a Black person could be snatched off the street and sent South without a real trial. Douglass pointed out the insanity: Americans would celebrate their escape from British "tyranny" (which was basically just taxes) while literally shackling human beings in the basement of the capital.

The Prescience of Globalization

One part of the speech that people rarely talk about is how Douglass mentioned technology. He talked about how the steam engine and the telegraph were "annihilating" space. He believed that because the world was becoming more connected, America couldn't hide its sins anymore. "Thoughts expressed on one side of the Atlantic are distinctly heard on the other," he said. He was basically predicting the internet's ability to expose human rights abuses in real-time.

Was He Anti-American?

This is where things get nuanced. A lot of people hear this speech and think Douglass hated the U.S.

Actually, the opposite is true.

Douglass was a "Constitutional optimist." His rival, William Lloyd Garrison, thought the Constitution was a "covenant with death" and should be burned. Douglass disagreed. In the final third of his speech, he argued that the Constitution is actually a "GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT."

He challenged anyone to find the word "slave" or "slavery" in it. (Spoiler: You can't). He believed that if the country just actually followed its own rules, slavery would have to die. He wasn't trying to tear down the house; he was demanding the owners actually live up to the lease they signed in 1776.

💡 You might also like: Was Trump Accused of Rape? What Really Happened (Simply)

Why It Hits Different Today

We still struggle with the "Two Americas" concept Douglass laid out. He spoke about the "measurable distance" between the platform he stood on and the slave plantation.

In 2026, we see this in the wealth gap, in the justice system, and in how history is taught in schools. When Douglass said, "It is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle shower, but thunder," he was calling for a radical honesty that most people still find uncomfortable.

Actionable Takeaways for Modern Readers

If you're looking to actually engage with the Frederick Douglass Fourth of July speech beyond just a quote, here’s how to do it:

- Read the full text: Most excerpts cut out the first 20 minutes where he praises the Founders. Without that context, you miss the "scorching irony" he was building.

- Study the 1850 context: Look up the Fugitive Slave Act. It makes his anger feel much more immediate and justified.

- Apply the "Transparency" test: Douglass used the "interconnected world" to argue for accountability. Ask yourself: If the whole world is watching our current actions, would we be proud or scrambling for excuses?

- Check the Constitution: Read it like Douglass did—looking for what isn't there. It changes how you view the "original intent" debate.

Frederick Douglass didn't leave his audience with despair. He ended with hope. He believed "the doom of slavery is certain." He saw the progress of the world and the "arm of the Lord" as forces that couldn't be stopped. He was right, though it took a bloody Civil War to prove it.

Next time July rolls around, remember that for Douglass, patriotism wasn't about ignoring the ugly parts of the country. It was about having enough faith in the "saving principles" of the nation to demand they actually apply to everyone.

To get the most out of this historical moment, you should compare the 1852 speech with his later 1875 address. In the latter, he started asking what "peace among the whites" would mean for Black liberty—a hauntingly accurate preview of the end of Reconstruction. Follow the trajectory of his hope; it’s the most honest map of the American spirit we have.