Frank Sinatra turned fifty and the world expected a party. Instead, they got a wake. Well, maybe not a wake, but a long, slow look in the mirror that most superstars would have been too terrified to share. When September of My Years dropped in 1965, it didn't just capture a moment in time; it basically invented the "concept album" for the grown-up set. Honestly, it’s the sound of a man realizing that the "wee small hours" aren't just for drinking anymore—they're for counting up what's left.

You've heard the hits. You know the swagger. But this record is something else entirely. It’s vulnerable. It’s a bit dusty. It’s Frank Sinatra admitting, in front of a live microphone and a full orchestra, that he’s getting old.

The 1965 Gamble: Sinatra at Fifty

Most people think of 1965 as the year of Beatlemania or the rise of the Rolling Stones. Rock and roll was eating the world. For a "saloon singer" like Sinatra, the easy move would have been to pivot toward the kids or just keep churning out the brassy, finger-snapping anthems that made him the Chairman of the Board. Instead, he teamed up with Gordon Jenkins.

If Nelson Riddle was the guy who made Sinatra swing, Gordon Jenkins was the guy who made him cry. Jenkins loved strings. Lush, weeping, unapologetic strings. He didn't care about a "beat" in the traditional sense. He cared about atmosphere.

Recording started in April 1965 at United Western Recorders in Hollywood. Sinatra was about to hit that big 5-0 milestone in December. You can hear it in the sessions. His voice had changed. The velvet was getting a little frayed around the edges, moving into a rich, oaken baritone that carried more weight. It wasn't about hitting the high notes anymore. It was about the "acting" of the song.

Why "It Was a Very Good Year" Almost Didn't Happen

It’s the centerpiece. The one everyone knows. But "It Was a Very Good Year" wasn't written for Sinatra. Ervin Drake wrote it in 1961 for The Kingston Trio. Think about that for a second. A folk group.

When Sinatra heard it, he saw the blueprint for his entire life. The song follows a man through his teens, his twenties, his thirties, and finally into the "autumn" of his life. Jenkins’ arrangement is a masterclass in storytelling. The way the woodwinds flutter during the "seventeen" verse, mimicking the flightiness of youth, versus the heavy, somber strings of the finale.

Sinatra's delivery of the line "it's ripe and it's mellow" isn't just singing. It's a statement of fact. He’s comparing his life to vintage wine, and even if the bottle is nearly empty, the taste is still worth the price.

The Tracks That Nobody Talks About (But Should)

Everyone focuses on the hits, but the deep cuts on September of My Years are where the real ghosts live. Take "Hello, Young Lovers." It’s a Rodgers and Hammerstein tune from The King and I. Usually, it’s sung with a sort of wistful encouragement. Sinatra turns it into something almost ghostly. He’s looking at the "young lovers" from a distance, acknowledging their joy while making it clear he can no longer join them. It’s heartbreaking.

Then there’s "Last Night When We Were Young."

Sinatra had recorded this before, but the 1965 version is the definitive one. It’s slow. Painfully slow. He lingers on the words. It’s the sound of a man realizing that "last night" was actually twenty years ago. The technical term for what he's doing here is rubato—stretching the tempo, pulling at the phrases like they’re pieces of taffy. He’s not following the conductor; the conductor is following him.

The Stan Cornyn Liner Notes

You can't talk about this album without mentioning the packaging. Stan Cornyn wrote the liner notes, and they won a Grammy for a reason. He described Sinatra in the studio: "He stands there, feet apart, shoulders slightly hunched, his hands in his pockets, his eyes closed. He’s not just singing; he’s remembering."

That’s the vibe. It’s not a performance for an audience. It’s a private confession that we just happen to be eavesdropping on.

The Technical Shift: From Swing to Soliloquy

Musically, this album broke the rules of the mid-sixties. While everyone else was turning up the volume, Sinatra turned it down.

- The Range: His voice sits lower in the mix.

- The Breath: You can hear him breathe. It’s intimate.

- The Pace: Most tracks are ballads. There is zero "swing" here.

- The Instrumentation: Heavy on the cellos and violas, light on the brass.

It was a risky move. In the business world, this is what you’d call a "brand pivot." He went from being the guy every man wanted to be and every woman wanted to be with, to being the guy who reminded you that your time is running out.

And it worked. The album won Album of the Year at the 1966 Grammys. It beat out the Beatles' Help! and The Sound of Music soundtrack. Let that sink in. In the height of the British Invasion, a 50-year-old guy singing about his "declining years" was the biggest thing in music.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Melancholy

There’s a common misconception that September of My Years is a depressing record. I don't buy that. Sorta the opposite, actually.

It’s an album about acceptance.

There’s a difference between being sad about getting old and being honest about it. Sinatra sounds resolved. In "September Song," when he sings about the days dwindling down to a "precious few," there’s a sense of urgency. It’s a reminder to live while you can. It’s not a funeral march; it’s a toast.

He was also dealing with his own personal chaos at the time. His marriage to Mia Farrow was on the horizon (they married in '66), and he was constantly hounded by the press. The studio was his only sanctuary. When he sang "The Man in the Looking Glass," he was literally staring at his own reflection in the vocal booth glass.

The Legacy of the "September" Sound

You can see the DNA of this album in almost every "late-career" masterpiece that followed.

When Johnny Cash did the American Recordings with Rick Rubin, he was pulling from the Sinatra playbook. When Bob Dylan released Shadows in the Night (his own tribute to Sinatra), he was chasing this exact atmosphere. Even modern artists like Adele or Lana Del Rey use that "cinematic melancholy" that Jenkins and Sinatra perfected here.

It taught the industry that you don't have to stay young to stay relevant. You just have to be real.

The Best Way to Experience the Record

Don't shuffle it. Please.

This is a front-to-back experience. You need the transition from the opening title track into "How Old Am I?" to understand the emotional arc. Put it on when the sun is going down. Grab a drink—bourbon, if you want to be authentic—and just sit there.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Listener

If you’re just diving into the Sinatra catalog or you’re a longtime fan who usually skips the "slow stuff," here is how to actually digest September of My Years:

📖 Related: Why Characters With Black Bobs Still Rule Pop Culture

- Listen for the "Acting": Ignore the melody for a second and just listen to how he says the words. Sinatra was a frustrated actor as much as he was a singer. Notice where he pauses.

- Compare the Versions: Listen to his 1940s or 50s versions of these songs. The difference in vocal texture tells the story of a human life.

- Check the Credits: Look up Gordon Jenkins. If you like this album, check out Nat King Cole Sings/George Shearing Plays for a similar "lush" vibe.

- Watch the TV Special: There’s a 1965 Emmy-winning special called A Man and His Music. It captures Sinatra during this exact era. You can see the intensity in his eyes when he performs these tracks.

September of My Years remains the gold standard for how to age with dignity in the public eye. It’s a reminder that the most powerful thing an artist can do is tell the truth, even if the truth is that they’re tired and the "days are growing short." It’s a masterpiece of the "autumn" of life, and honestly, it’s just as relevant today as it was sixty years ago.

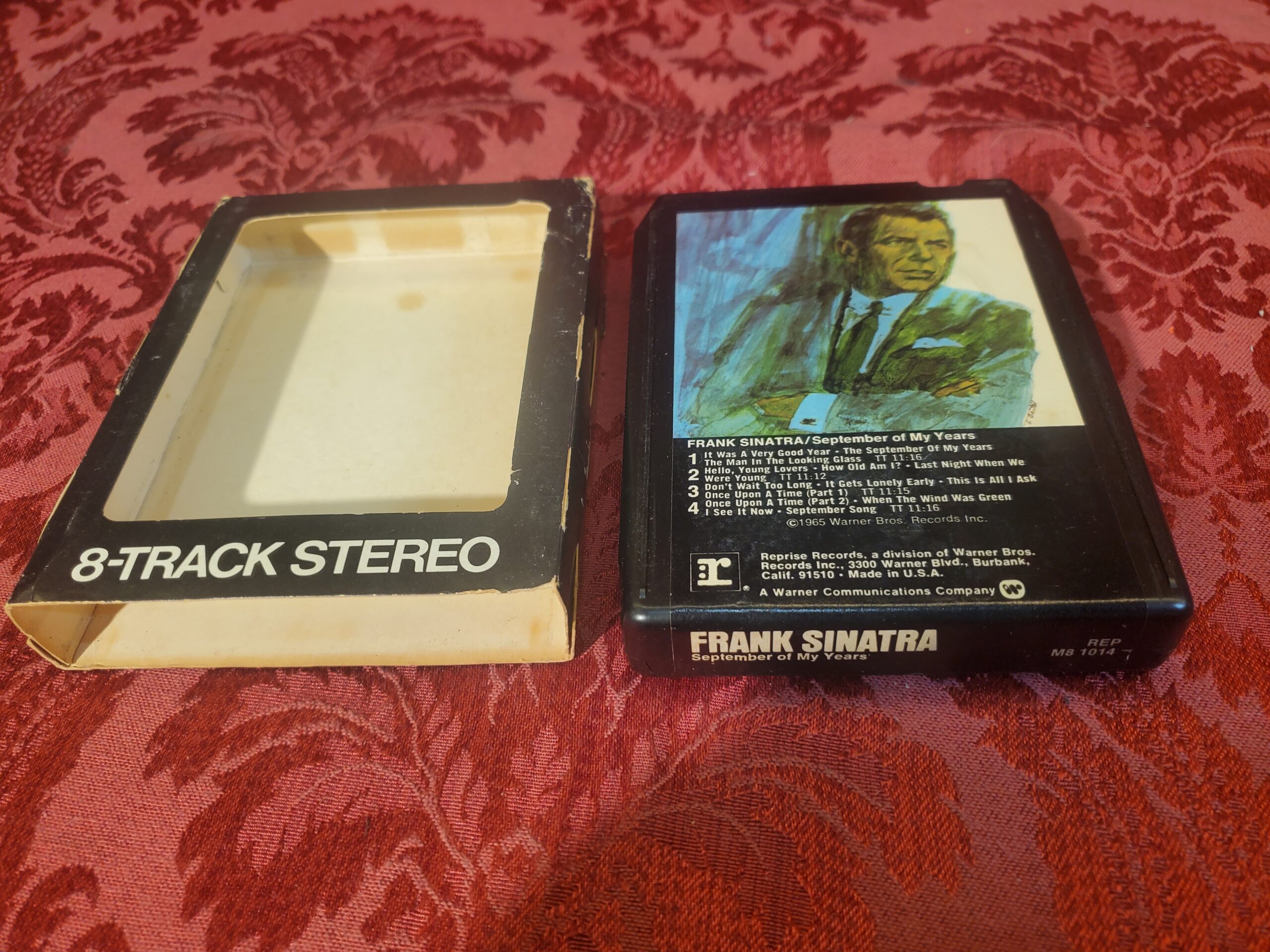

For those looking to build a vinyl collection, seek out the original 1965 Reprise stereo pressing. While the mono versions have their fans, the stereo mix allows the Gordon Jenkins arrangements to breathe in a way that feels like the orchestra is sitting right in the room with you. If you're on streaming, look for the 2015 remastered version, which cleaned up some of the tape hiss without losing the warmth of the original sessions.