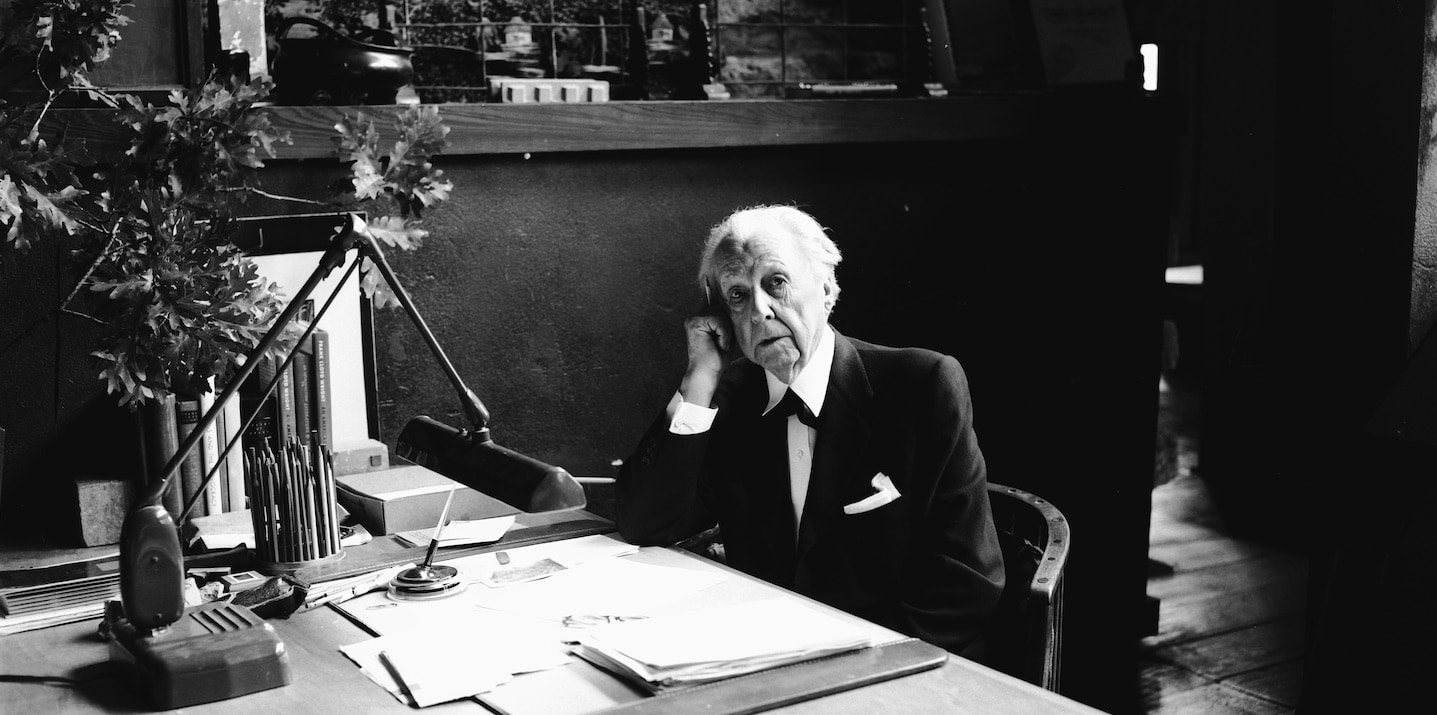

You’ve probably seen the photos of Fallingwater. It’s that house perched over a waterfall in Pennsylvania that looks like it’s growing out of the rocks. Most people see it and think "genius." But if you talked to the owners, the Kaufmann family, back in the 1930s, they might have used different words. Like "expensive." Or "leaky." Especially "leaky." Frank Lloyd Wright was many things—a visionary, a rebel, a bit of a narcissist, and arguably the most influential architect in American history—but he was never, ever boring.

He didn't just build houses. He tried to rewrite how humans live.

Most architects of his time were obsessed with copying Europe. They wanted big marble columns and stuffy Victorian rooms that felt like tiny boxes stitched together. Wright hated that. He called it "fascist" in its own way, or at least spiritually suffocating. He wanted an American architecture. Something that breathed. He called it Organic Architecture, and honestly, we’re still trying to catch up to what he was doing over a century ago.

The Prairie Style and the Death of the Room

Before the world knew him for spirals and concrete, Frank Lloyd Wright was busy in Chicago. He was part of the "Prairie School." The idea was simple: the Midwest is flat. Why are we building tall, skinny houses with steep roofs? It looks weird.

He started designing homes with long, horizontal lines. They hugged the ground. He got rid of the walls between the kitchen, the dining room, and the living room. If you live in a modern house with an "open floor plan," you basically owe Wright a thank you note. He did it first.

Take the Robie House in Chicago. It’s the peak of this style. It has these massive cantilevered rooflines that seem to defy gravity. People at the time thought it looked like a steamship or something from another planet. Wright didn't care. He was obsessed with the "hearth"—the fireplace—as the center of the home. Everything rotated around the fire. It was primal but sophisticated.

He was also kind of a control freak.

If Wright designed your house, he usually wanted to design your chairs, your tables, your rugs, and even your napkins. There’s a famous story—maybe a bit exaggerated, but true in spirit—of Wright visiting a client and moving a vase of flowers because it "ruined the line" of the room. He didn't just want to give you a building; he wanted to give you a lifestyle.

Success, Scandal, and the Taliesin Tragedy

You can’t talk about the man without the drama. His life was a soap opera. In 1909, he left his wife and six children to run off to Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney, who was the wife of one of his clients. The scandal nearly killed his career. The press was brutal.

💡 You might also like: Why 5church Charleston Charleston SC is Actually Worth the Hype

He retreated to Wisconsin and built Taliesin. It was his sanctuary.

But in 1914, horror struck. While Wright was away working in Chicago, a servant set fire to the living quarters and murdered Mamah, her two children, and four others with an axe. It’s one of the most grisly, heartbreaking moments in American history. Most men would have folded. Wright? He rebuilt. He used the tragedy to fuel a sort of defiant, manic creativity that lasted for the next forty years.

Fallingwater and the Great Comeback

By the 1930s, everyone thought Wright was washed up. He was in his 60s. The "International Style" (think glass boxes and steel) was the new cool thing. Critics called him a "has-been."

Then came Fallingwater.

Edgar Kaufmann, a department store magnate, wanted a summer cabin with a view of the falls. Wright decided to build the house on top of the falls. When Kaufmann saw the plans, he was terrified. He actually went behind Wright's back to hire engineers to check the math on the concrete slabs. Wright found out, got insulted, and threatened to quit.

The house stayed. It’s now a UNESCO World Heritage site. It’s arguably the most famous private residence in the world. It proved that Wright wasn't just an old guy with a cape and a cane—he was still the master.

He followed that up with the Johnson Wax Headquarters. If you've ever seen those "lily pad" columns that look like they’re floating in a forest of glass, that’s the place. He was experimenting with materials like Pyrex glass tubing and reinforced concrete in ways no one else dared. He was basically playing with the physics of the future.

The Guggenheim: A Final Middle Finger to Tradition

Wright’s last great act was the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City. He spent 16 years on it. He died six months before it opened in 1959.

The art world hated the design at first. Artists actually signed a petition saying the curved walls weren't suitable for hanging paintings. They weren't entirely wrong—it’s a nightmare to hang a flat canvas on a curved, sloping wall. But Wright didn't care about the paintings as much as he cared about the experience of the space.

He wanted you to take the elevator to the top and drift down the ramp. It was a "temple of spirit." Today, it’s the building people go to see, often more than the art inside it. It’s the ultimate testament to his belief that architecture is the "mother of all arts."

What Most People Get Wrong About His Houses

There’s a common myth that Wright houses are "unlivable."

Yes, they have issues. He used flat roofs in places with heavy snow (bad idea). He often used experimental materials that didn't age well. And if you’re taller than 6 feet, his "compression and release" technique—where he makes entryways very low and cramped to make the main room feel huge—can feel a bit claustrophobic.

But he was also a pioneer of sustainability before it was a buzzword. He used local stone. He used passive solar heating. He understood that a building should belong to its site. "No house should ever be on a hill or on anything," he said. "It should be of the hill. Belonging to it."

He also invented the Usonian house. These were meant to be affordable homes for the average American family. No basements, no attics, small kitchens, and lots of built-in furniture to save space. They were the precursor to the modern ranch house. He actually cared about how the middle class lived, even if his ego suggested otherwise.

How to Experience Wright Today

If you really want to understand his work, you can't just look at pictures. You have to feel the scale.

- Visit Oak Park, Illinois: This is where it started. You can walk the neighborhood and see the largest collection of his early work.

- Tour Taliesin West: His winter home in Scottsdale, Arizona. It’s built out of desert rock and sand. It feels like it was unearthed, not built.

- Stay in a Wright house: You can actually rent some of his Usonian designs on sites like Airbnb or through specific conservancies. Living in one for a night changes how you see light and shadows.

- The Price Tower: It's his only skyscraper, located in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. It's weird, green, and totally unique.

Frank Lloyd Wright was a man of contradictions. He preached democracy but acted like an aristocrat. He loved nature but often ignored the practical realities of weather. But he changed everything. Every time you sit in an open-concept living room or look out a large picture window, you’re living in his shadow.

Practical Steps for Architecture Enthusiasts

If you’re looking to bring a bit of his philosophy into your own life without building a cantilevered masterpiece, focus on these three things:

💡 You might also like: Finding the Right Vibe: Girl Names with a T That Don't Feel Dated

- Bring the outside in. Wright used massive windows and natural materials to blur the line between the living room and the garden. Even adding more plants or using natural wood finishes can change the "vibe" of a space.

- Declutter the "box." Wright hated "dead space" like attics and basements that just collect junk. He preferred built-in storage that kept the floor plan clean.

- Respect the site. If you're renovating or building, look at the land first. Don't fight the slope of your yard; work with it.

His legacy isn't just about old buildings. It's about the idea that the space we inhabit dictates the people we become. He wanted us to be more connected, more grounded, and a little bit more daring. Not a bad way to look at the world.