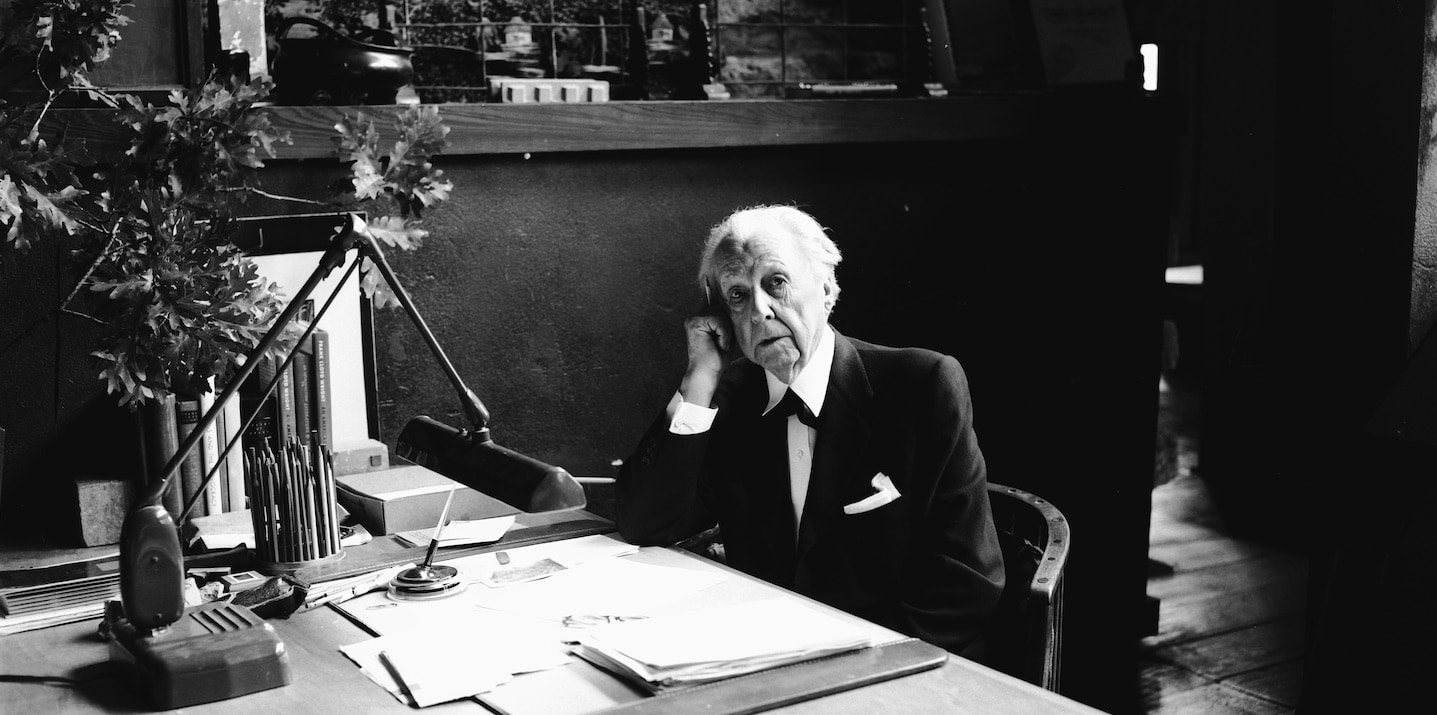

Frank Lloyd Wright was a mess. A brilliant, world-altering, ego-driven mess. If you look at a Frank Lloyd Wright biography today, you’ll see the glossy photos of Fallingwater or the spiral of the Guggenheim, but the man behind the drafting table was far more complicated than a textbook hero. He was a guy who spent money he didn’t have, abandoned his family for a client’s wife, and somehow survived a literal hatchet massacre at his own home.

He changed how we live. Seriously.

Before Wright, American houses were basically cramped boxes with tiny windows. He hated that. He wanted homes to breathe. He called it organic architecture, a fancy way of saying a building should look like it grew out of the ground rather than being dropped onto it.

👉 See also: Cleaning a Chair With Cum Stains Without Ruining the Fabric

The Wisconsin Roots Most People Skip

Born in 1867 in Richland Center, Wisconsin, Frank wasn't exactly a child of privilege. His father was a preacher who eventually walked out, and his mother, Anna Lloyd Jones, was—to put it mildly—intense. She apparently decided he’d be an architect before he was even born. She gave him Froebel Blocks to play with, which were these geometric wooden toys that taught him how to see the world in shapes.

He never actually finished a formal architecture degree. He did a couple of semesters at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, but he was too restless. He headed to Chicago, the only place that mattered for a young builder in the late 1880s.

Eventually, he landed a job with Louis Sullivan, the "father of skyscrapers." Sullivan became his lieber meister (dear master). Wright learned everything from him, but he also started designing houses on the side—"bootleg" houses—to pay his mounting debts. Sullivan found out and fired him.

That was the start of the independent Frank Lloyd Wright we know.

The Prairie School: Killing the Box

Between 1900 and 1910, Wright basically invented the "Prairie Style." He looked at the flat, horizontal landscape of the Midwest and thought, Why are our houses tall and skinny? He started building homes with:

- Low, sloping rooflines.

- Hidden entrances.

- Huge, open living spaces.

- Ribbon windows that blurred the line between inside and out.

The Robie House in Chicago is the peak of this. It looks like it’s moving even when it’s standing still. But while his professional life was exploding, his personal life was a wreck. He was bored. He was married with six kids, but he felt "trapped."

So, he did something unthinkable in 1909.

He ran off to Europe with Mamah Borthwick Cheney, who happened to be the wife of one of his neighbors and clients. The press had a field day. He was a pariah. To escape the noise, he moved back to Wisconsin and started building Taliesin, his "shining brow" on a hill.

The Night Everything Changed

Most people don't realize how dark the Frank Lloyd Wright biography gets. In August 1914, while Wright was working in Chicago, a servant at Taliesin named Julian Carlton went on a rampage.

He set the house on fire and stood by the only exit with a hatchet.

✨ Don't miss: What Does It Mean Ditto: Why This Old School Word Is Suddenly Everywhere Again

He murdered seven people, including Mamah and her two children. Wright was devastated. He buried her in an unmarked grave and stayed on the property, obsessively rebuilding. It’s honestly kind of chilling. Most people would have moved away, but Wright just kept building on the ashes. He called the new version Taliesin II.

Fallingwater and the Great Comeback

By the late 1920s, Wright was considered a "has-been." He was in his 60s. The younger generation thought his stuff was dated. He was broke, and the FBI was even sniffing around his personal life (he had a massive dossier because of his anti-war views and some messy legal battles).

Then came Fallingwater.

In 1935, a department store mogul named Edgar Kaufmann asked Wright to design a weekend retreat in Pennsylvania. The Kaufmanns loved a specific waterfall on their property and wanted a house with a view of it.

Wright did them one better. He built the house on top of the waterfall.

He didn't even start the drawings until Kaufmann called him and said he was on his way to see them. Wright supposedly sat down and drew the whole thing in about two hours. It’s a miracle of engineering, using cantilevers—beams anchored at only one end—to make concrete floors hover over the rushing water.

The Guggenheim: A Final Act of Defiance

Wright spent the last 15 years of his life fighting New York City. He hated the "grid" of Manhattan. He thought it was a "man-trap." When he was commissioned to build the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, he designed a giant white spiral.

🔗 Read more: Is Daylight Savings Time Tomorrow? Why We’re Still Doing This and How to Survive the Shift

Critics hated it. Artists signed petitions saying their paintings couldn't be shown on slanting walls.

Wright didn't care. He told them they were lucky to be in his building. He died in 1959 at the age of 91, just six months before the museum opened. He never saw the finished product, but it remains the most famous building in the world’s most famous city.

Why He Still Matters (The Actionable Takeaway)

You don't have to be an architect to learn from Frank Lloyd Wright. His life was a lesson in persistence and vision. He was frequently "canceled" by society, bankrupt, and aging, yet he produced his best work when most people were retiring.

If you want to experience his legacy today, don't just read about it.

- Visit a Usonian home: These were his "everyman" houses. Many are now Airbnbs or open for tours. They show you how to live well in a small space.

- Look at your windows: Wright taught us that a house is not a fortress. Try to bring the outside in. Add plants, use natural materials, and ditch the heavy curtains.

- Embrace the "Open Plan": If you love your open-concept kitchen and living room, you can thank Frank. He pioneered that flow over 100 years ago.

Honestly, the best way to understand the man is to stand inside one of his buildings. They feel different. They’re lower, more intimate, and somehow more human. Wright was a flawed man, but he understood one thing perfectly: architecture isn't about the walls; it's about the space inside the walls.

To really dive into the technical side of his genius, start by looking up the Taliesin Fellowship. It was his school where students literally built their own shelters in the desert. It’s a wild look at how he trained the next generation to see the world through his "organic" lens.