Imagine standing at the base of a building so tall that it literally pierces the clouds. Not just a skyscraper, but a needle of steel and glass reaching 5,280 feet into the sky. That was the dream of The Mile High Illinois. In 1956, Frank Lloyd Wright stood before a crowd in Chicago and unveiled a vision that made the Sears Tower look like a bungalow. It wasn't just a tall building. It was a city.

He called it "The Illinois."

Most people think Wright was just being an ego-driven dreamer when he drew up the plans for The Mile High Illinois. Honestly, they might be right. But if you look at the technical specs he proposed, you start to realize he wasn't just sketching a fantasy. He was trying to solve the problem of urban sprawl before it even became the nightmare it is today. He hated how cities were spreading out like ink blots, eating up the countryside. His solution? Go up. Way up.

The Absolute Madness of the 528-Story Design

Think about the scale here. A mile is 5,280 feet. For context, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, currently the tallest building on the planet, stands at 2,717 feet. Wright wanted to double that in the mid-1950s. It’s wild. The structure was designed to house 130,000 people. That is the entire population of a mid-sized city living in one single footprint.

He didn't want it to look like a box.

✨ Don't miss: The SwissMiniGun Explained: Why the World's Smallest Gun is Actually a Felony in the US

The building was shaped like a tripod needle. Wright understood wind loads better than almost anyone of his era. He knew that at 5,000 feet, the wind isn't just a breeze; it’s a physical force that can snap a rigid structure. By using a tripod shape, he gave the building a wide, stable base that tapered as it rose. This "taproot" foundation concept was inspired by trees. He wanted to bury the base deep into the bedrock of Chicago, almost like a giant tooth.

How do you move 100,000 people?

Elevators were the biggest hurdle. You can't just have one elevator going from the ground to the top; the cables would be too heavy to even lift themselves. Wright’s solution for The Mile High Illinois was visionary. He proposed nuclear-powered elevators. Yes, nuclear. He imagined five-story-high cabs that would move at incredible speeds.

It sounds like sci-fi.

But today, we see versions of this in "sky lobbies." In modern supertalls, you take an express elevator to a transfer floor, then switch to a local one. Wright was basically predicting the logistics of the 21st-century skyscraper seventy years early.

The Materials That Didn't Exist Yet

One of the biggest reasons The Mile High Illinois stayed on paper was the weight. In 1956, steel was heavy. If you built a mile-high tower out of standard structural steel from that era, the bottom floors would have been crushed by the weight of the top floors. Wright talked about using "tapered steel" and high-tension reinforcements.

He was waiting for materials science to catch up.

We now have high-strength concrete and carbon fiber, but back then? It was a stretch. Critics at the time, including many of Wright's peers, thought the building would sway so much that people on the upper floors would get seasick. Wright disagreed. He argued the tripod shape and the tension-stressed steel would make it "as rigid as a willow tree," which is a bit of a contradiction, but you get what he was aiming for.

💡 You might also like: Why the 2000 military containment unit is still the backbone of secure storage

The Cost of the Dream

Nobody actually knows how much it would have cost. Estimates at the time were in the hundreds of millions, which in 1950s money is billions today. Chicago didn't have the budget. The world didn't have the appetite for that kind of risk. Plus, there was the ego factor. Wright was nearly 90 years old when he proposed this. Some saw it as a final, grand gesture from a man who knew his time was running out.

Why The Mile High Illinois Still Matters

You might wonder why we still talk about a building that was never even close to being built. It’s because it changed the DNA of architecture. When engineers were designing the Burj Khalifa, they looked at Wright’s tripod design. They used a "buttressed core," which is essentially a modern, sophisticated version of Wright's 1956 plan.

The "Illinois" proved that we could think about verticality as a solution to human density.

- Vertical Cities: Instead of commuting two hours from a suburb, you live, work, and shop in the same spire.

- Land Preservation: By building up, you leave the surrounding land for parks and nature.

- Structural Innovation: The transition from "frames" to "tubes" and "tripods" started here.

The Mile High Illinois wasn't just a building; it was a challenge. It told the world that the sky wasn't a limit, just a temporary ceiling.

👉 See also: Apple Desktop Monitor: Why Buying One Is Kinda Complicated Right Now

The Ghost of the Tower in Modern Chicago

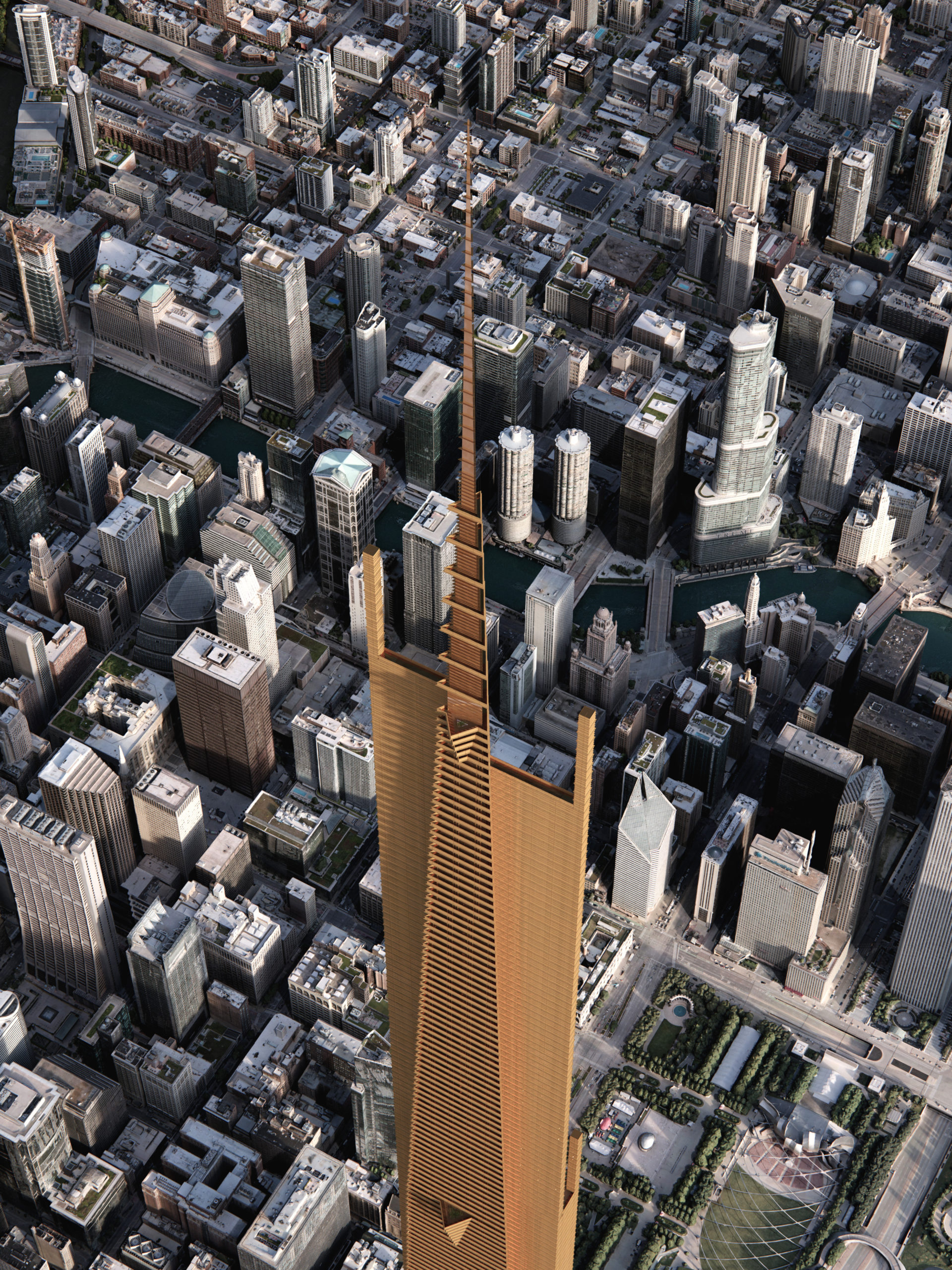

If you go to Chicago today, you see its influence everywhere. You see it in the tapered silhouette of the John Hancock Center. You see it in the ambition of the failed Chicago Spire project.

Wright’s "Illinois" would have stood near the lakefront. It would have cast a shadow miles long. It would have been visible from states away on a clear day. Even though it's just a set of drawings in an archive now, it remains the benchmark for "impossible" architecture.

It’s easy to call it a failure because it isn't there. But in the world of design, a "failure" that inspires the tallest buildings on Earth for the next century is actually a massive success.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts and Urban Planners

If you want to understand the real-world physics behind Wright's dream, you should start by looking into the buttressed core system used in the Burj Khalifa. It is the direct descendant of the Illinois tripod.

For those interested in the history, a trip to Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin is non-negotiable. Seeing the original sketches in person gives you a sense of the sheer scale that a digital screen just can't replicate. You can also research the Skyscraper Museum's digital archives, which often feature "unbuilt" exhibits focusing on the technical hurdles Wright faced.

Finally, look into modern Modular Construction and Carbon Fiber Reinforcement. These are the technologies that might actually make a mile-high structure viable in our lifetime. Wright had the vision; we finally have the tools.

Check out the original 1956 press conference photos if you can find them. The look on the faces of the reporters as Wright unveiled a 22-foot-long drawing of the tower says everything you need to know about how radical this idea truly was. It wasn't just a blueprint. It was a dare.