Honestly, if you want to understand why Francis Bacon’s art feels like a punch to the gut, you have to look at the man who was paying for the gloves. That was Eric Hall. He wasn't just a patron; he was Bacon's lover, his sugar daddy, and the guy who basically kept the lights on when Bacon was more interested in the roulette wheel than the easel.

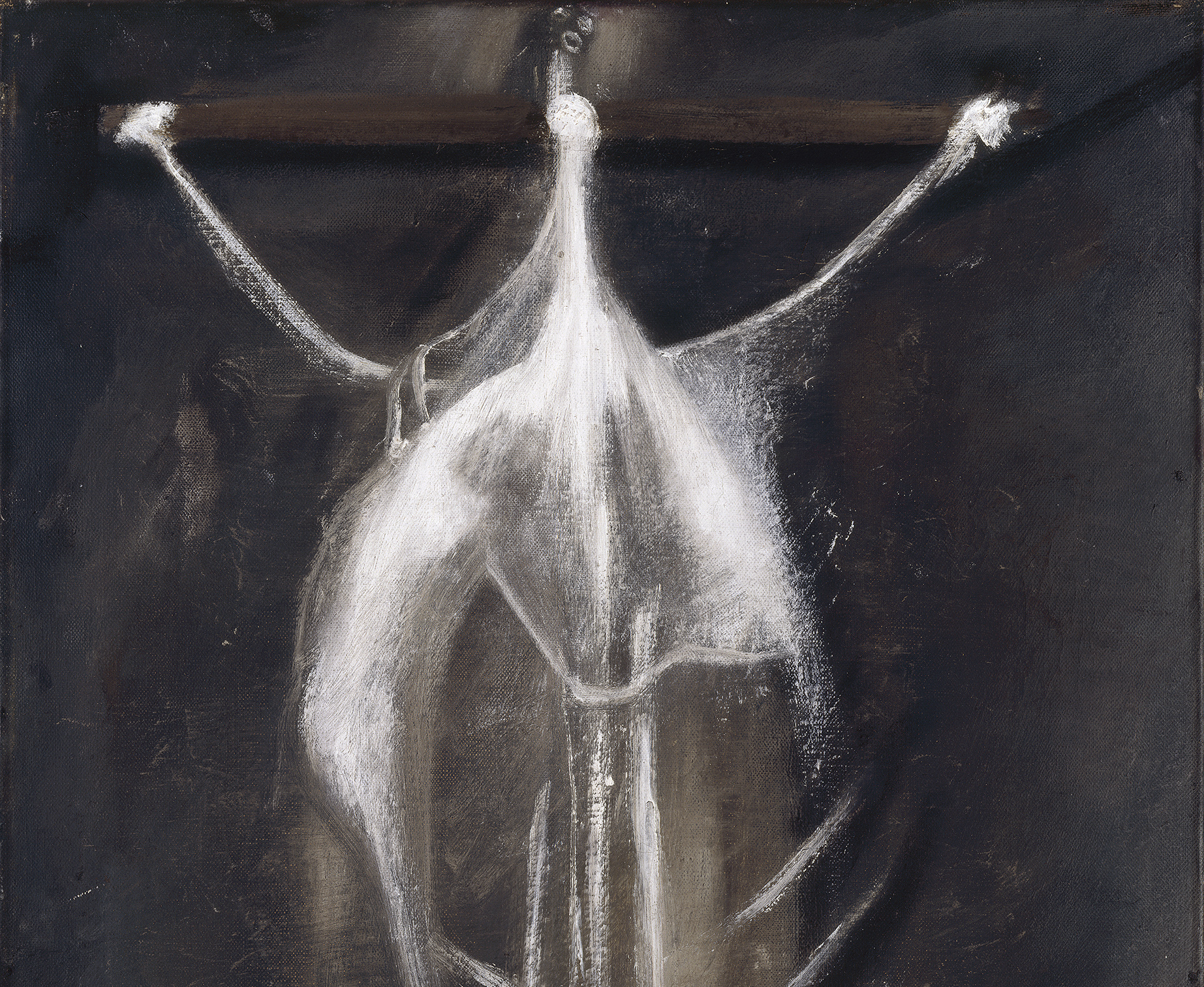

People talk about Bacon’s "Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion" as this sudden, divine spark of genius that changed British art in 1944. But it wasn't a solo act. Without Eric Hall, that painting—and many others—might have ended up in a dumpster or never been finished at all. It’s a wild story of a married businessman, an asthmatic painter, and a nanny who lived in the kitchen.

The Man Behind the Money (and the Meat)

Eric Walter Hall was seventeen years older than Bacon. He was a wealthy businessman, a husband, a father, and even the Chairman of a London symphony orchestra. On paper, he was the pillar of respectability. In reality? He was head over heels for Francis Bacon. They met around 1932, likely at the Bath Club in Mayfair, where Bacon was actually working at the telephone exchange. Think about that for a second. One of the 20th century's greatest artists was literally plugging in phone lines while a millionaire fell for him.

Hall didn't just buy a few paintings. He moved in. He, Bacon, and Bacon's childhood nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, formed this bizarre, avant-garde household. They lived together in South Kensington and eventually decamped to Monaco.

What Everyone Gets Wrong About the Portraits

You’ll often hear people ask, "Which Francis Bacon and Eric Hall painting is the most famous?" Here is the kicker: there technically isn’t a surviving "standard" portrait of Hall by Bacon.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

Bacon was notorious for destroying his own work. If he didn't like it, he slashed it. He once said Eric "never let me down," but apparently, the canvases didn't always live up to that devotion. X-ray analysis of the right-hand panel of Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion actually shows what researchers believe is a likeness of Hall hidden underneath the final screaming figure. He literally painted over his lover to create a monster.

But there is one painting that is, for all intents and purposes, a portrait of Hall.

- Figure in a Landscape (1945): This one is based on a lost photograph of Eric Hall dozing in a chair in Hyde Park.

- The Vibe: It’s not a peaceful nap. The figure is headless. There's a bank of microphones in front of him. It looks like a politician about to give a speech or a victim in an interrogation room.

- The Detail: Hall was wearing a specific suit in that photo, and you can see the echo of that middle-class attire in the painting. It’s Bacon’s way of taking the man he loved and turning him into "the human animal."

Why the Relationship Mattered for the Art

Hall was the one who pushed Bacon to take painting seriously again. In the late 30s, Bacon was frustrated. He wasn't selling. He was being compared to Picasso and losing. He basically quit to go gambling. Hall was the one who provided the "Petersfield" studio in Hampshire where Bacon worked during the war.

He also broadened Bacon’s mind. He introduced him to Greek tragedies like the Oresteia and the works of Shakespeare. If you look at those screaming mouths and the "Furies" in Bacon’s work, you’re seeing Eric Hall’s intellectual influence. Hall even bought Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion and eventually donated it to the Tate Gallery in 1953. Without that donation, Bacon’s legacy might look very different today.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

The Monte Carlo Years

By 1946, the pair moved to Monaco. It was a disaster for the art, but great for the drama. Bacon was obsessed with the casino. He’d lose all his money, then Hall would bail him out.

Interestingly, it was in Monaco that Bacon started his famous "Pope" series. He also started painting on the "wrong" side of the canvas—the unprimed, rough side. Why? Because he had run out of money for new supplies and was too lazy or broke to get more, so he just flipped the old ones over. That gritty, textured look that defines Bacon’s masterpieces was born from a gambling debt in a house paid for by Eric Hall.

The End of the Affair

The romance didn't last forever. By late 1948, Hall had left their shared home in Monaco. The relationship was often described as "torturous." Bacon wasn't exactly an easy partner. He was masochistic, prone to disappearing acts, and eventually moved on to the more violent and chaotic Peter Lacy.

But Hall never really left. Even after they split, he continued to support Bacon. He remained a loyal patron. When Bacon started painting figures with cricket pads in the 1970s and 80s—long after Hall had died—many critics saw it as a tribute. Hall had been a massive cricket fan. It was a small, strangely domestic nod to the man who had seen the genius in the phone operator.

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

What You Can Learn From Their Story

If you're looking at a Francis Bacon and Eric Hall painting today, don't just see the distortion. See the support system. Art history loves the "lonely genius" myth, but Bacon was a collaborative effort.

- Look for the "Space-Frame": Notice how Bacon boxes his figures in? That sense of isolation often mirrored the claustrophobic, "secret" nature of his relationship with Hall in a time when homosexuality was illegal.

- The Hidden Portraits: Check out the X-ray scans of Bacon’s 1940s work online. Seeing the "normal" face of Eric Hall underneath the screaming furies is a masterclass in how Bacon processed reality.

- Visit the Tate: Go see the Three Studies. Remember that a lover’s gift is why it’s standing there in front of you.

To truly understand Bacon, you have to accept that his "horrific" images were often born out of deep, albeit messy, affection. He didn't paint the scream because he hated the world; he painted it because he was trying to find the "pulsating" truth of being alive, a truth Eric Hall helped him find.

To see this influence in person, your best bet is a trip to the Tate Britain in London. They hold the core works that Hall either purchased or influenced. If you can't make it to London, many of these pieces are part of the MB Art Foundation’s digital archives, which specialize in the Monaco years. Examining the shift in Bacon's technique from 1945 to 1950 provides the clearest evidence of how Hall's presence—and eventual absence—shaped the most iconic era of British figurative art.