You've seen the diagrams. Those tall, silver towers at refineries that look like giant metal cigars reaching for the sky. Most people drive past them and think "pollution" or "gasoline," but there’s a massive, invisible sorting game happening inside those columns every single second. Without the fractional distillation of crude petroleum, your world basically stops moving. No, seriously. It isn't just about the gas in your tank; it’s the aspirin in your cabinet, the polyester in your shirt, and the asphalt keeping your tires on the road.

Crude oil is a mess. Honestly, it’s a thick, stinking soup of hydrocarbons. If you tried to put raw crude into your car, the engine would seize up before you reached the end of the driveway. You have to break that soup apart. You have to unmix the unmixable.

The Chaos Inside the Column

Let’s get into how this actually works. It starts with heat. Lots of it.

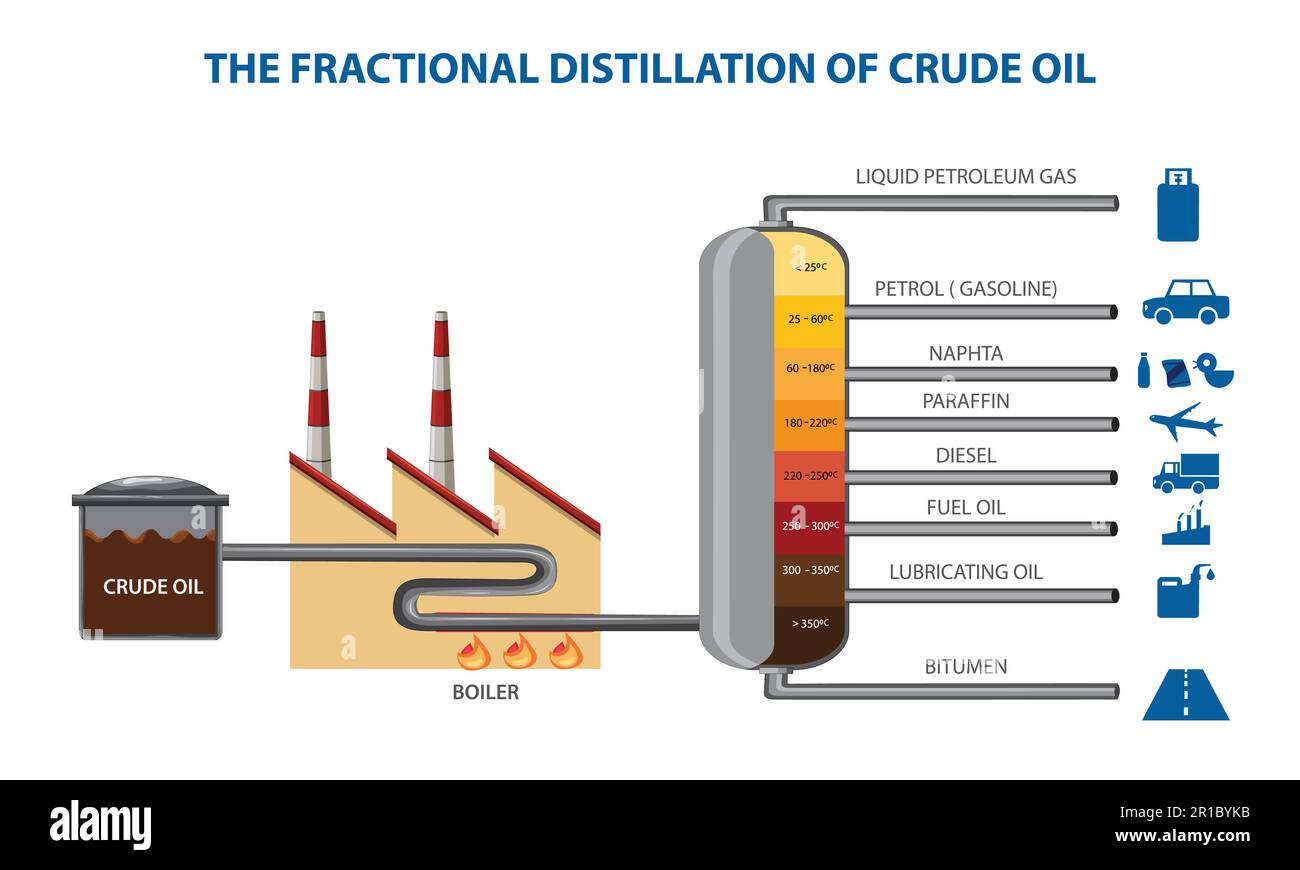

Before the crude even touches the distillation tower, it’s shoved through a furnace. We’re talking temperatures around 350°C to 400°C. At this point, most of the oil turns into a hot, angry vapor. This mist gets blasted into the bottom of the fractionating column. This tower is the heart of the whole operation. It’s a massive vertical cylinder filled with "trays" or "plates."

Here’s the trick: the tower is hottest at the bottom and gets cooler as you go up. This temperature gradient is the secret sauce.

As the vapor rises, it starts to cool down. Now, chemistry 101 kicks in. Different hydrocarbons have different boiling points based on how many carbon atoms they’re lugging around. The "heavy" stuff—the long chains with 20 or more carbon atoms—condenses back into a liquid almost immediately at the bottom. The "light" stuff—the short chains with only 1 to 4 carbons—stays as a gas all the way to the very top.

🔗 Read more: Why the Star Trek Flip Phone Still Defines How We Think About Gadgets

It’s a literal race to the top where the losers fall out as liquids at different floors.

Why the Trays Matter

You might wonder why it’s not just an empty pipe. If it were empty, the vapors would just mix and stay messy. The trays are designed with "bubble caps" or valves. Imagine a floor with little umbrellas on it. The rising vapor has to bubble through the liquid already sitting on that tray. This creates "reflux." It’s a constant scrub-down where the heavier molecules get knocked out of the gas and trapped in the liquid, while the lighter ones get a boost upward.

It’s remarkably efficient.

Breaking Down the "Cuts"

Refining engineers don’t call them "layers." They call them "fractions" or "cuts." Each cut serves a specific purpose in the global economy.

- Refinery Gases: These are the lightweights. Methane, ethane, propane. They never condense in the tower. They’re piped off the top. You use these for heating or as "feedstock" for making plastics.

- Gasoline (Petrol): This is the sweet spot. Usually 5 to 10 carbon atoms. It condenses near the top. Interestingly, a barrel of crude oil only naturally yields about 20% gasoline through distillation. To get more, refineries have to use "cracking," but that’s a whole different story involving breaking molecules apart with catalysts.

- Naphtha: This is the stuff nobody talks about but everyone uses. It’s the bridge between gas and kerosene. It’s the raw material for the entire petrochemical industry. If you like your iPhone case or your nylon yoga pants, thank naphtha.

- Kerosene: Jet fuel. If you're flying to London, this is what's keeping you in the air. It’s slightly heavier than gas, so it sits a bit lower in the tower.

- Diesel and Gas Oils: The workhorses. Trucks, trains, and heating oil.

- Fuel Oil: This is thick. It's used for massive ship engines and power stations.

- Bitumen and Residue: The "bottom of the barrel." It’s black, gooey, and doesn't boil at these temperatures. We use it to pave roads and seal roofs. It’s the leftovers of the prehistoric life forms that turned into oil millions of years ago.

The Real-World Complexity Most People Ignore

I’ve made it sound simple, right? Heat it up, let it cool, grab the liquid. But in a real refinery like the Reliance Industries facility in Jamnagar or the ExxonMobil plant in Baytown, the math is staggering.

💡 You might also like: Meta Quest 3 Bundle: What Most People Get Wrong

The crude oil entering the tower isn't always the same. "Sweet" crude from West Texas is easy to distill because it has low sulfur. "Sour" crude from other regions is a nightmare. It’s corrosive. If the distillation process doesn't account for sulfur, the entire tower can literally rot from the inside out. This is why chemical engineers are paid the big bucks—they have to constantly adjust the pressure and temperature of the tower based on the "flavor" of oil coming in that day.

Also, we have to talk about Vacuum Distillation.

Remember how I said we heat the oil to 400°C? If we went any higher, the oil would "crack" or burn into pure coke (carbon) right inside the pipes. That’s bad. It clogs everything. But we still have heavy oils left over that haven't boiled yet. To get those out, we move the leftovers to a second tower that operates under a vacuum. By lowering the pressure, we lower the boiling point. It’s the same reason water boils faster on top of Mt. Everest. This allows us to pull out lubricating oils and waxes without destroying the molecules.

Why This Still Matters in 2026

We hear a lot about the energy transition. Electric cars are everywhere. But here is the reality: even if we stopped burning gasoline tomorrow, we would still need the fractional distillation of crude petroleum.

Why? Because of the "non-energy" fractions.

📖 Related: Is Duo Dead? The Truth About Google’s Messy App Mergers

Lubricants. Greases. The feedstock for medical-grade plastics used in heart valves. The specialized solvents used to manufacture semiconductors. Currently, there is no "green" version of a distillation tower that can produce these specific long-chain hydrocarbons at the scale the world demands. We are getting better at bio-based plastics, sure. But for now, the fractionating column is the backbone of modern civilization’s physical objects.

The Environmental Elephant in the Room

Refineries are getting hammered on carbon emissions, and rightly so. The furnace used to heat the crude is a massive CO2 source. Modern tech is shifting toward "electrified" heating or using hydrogen to fire those furnaces. There’s also a huge push for "Digital Twins"—using AI to simulate the inside of the tower in real-time. By predicting exactly when a tray is about to flood or go dry, they can shave 1% or 2% off the energy bill. In a refinery processing 500,000 barrels a day, 2% is a massive win for the planet and the ledger.

Practical Insights for the Curious

If you're studying this or just trying to understand the industry, stop thinking of oil as "fuel." Think of it as a library of molecules. Fractional distillation is just the librarian sorting the books by height.

What you should do next:

- Check the "Bottoms": If you’re looking at energy stocks or environmental reports, look at the "complexity index" of a refinery. High-complexity refineries have more vacuum distillation and cracking units, meaning they can turn the cheap, "gross" bottom-of-the-barrel sludge into expensive gasoline. That’s where the profit is.

- Follow the Petrochemicals: Keep an eye on the "Naphtha" spread. When naphtha prices spike, the price of everything from plastic bottles to paint goes up a few months later. It's the ultimate leading indicator for inflation in consumer goods.

- Look at the Labels: Next time you see "Bitumen" on a construction site or "Paraffin" on a candle, remember that those molecules were once part of a 400-degree vapor cloud inside a giant silver tower.

The process is old. The first patents go back to the mid-1800s. But the physics of the fractional distillation of crude petroleum are as relevant today as they were during the first oil boom. It’s a brutal, beautiful, and incredibly hot dance of molecules that keeps the lights on and the world moving.