You're staring at a tiny, beige cylinder. It has four colored stripes. It’s smaller than a grain of rice, yet it’s the only thing keeping your expensive microcontroller from turning into a puff of blue smoke. Understanding the four band resistor color code isn't just some dusty academic exercise from a 1970s vocational school. It is survival gear for anyone who builds, fixes, or breaks electronics.

Honestly, it looks like a secret language. In a way, it is. Before automated pick-and-place machines and laser marking became the norm, engineers needed a way to identify components that were too small for printed numbers. Even today, when you're digging through a bargain bin of components from a surplus shop, those colors are your only roadmap.

The Logic Behind the Stripes

Most people think you just read them left to right and you're done. Wrong. The hardest part is actually figuring out which end is "left."

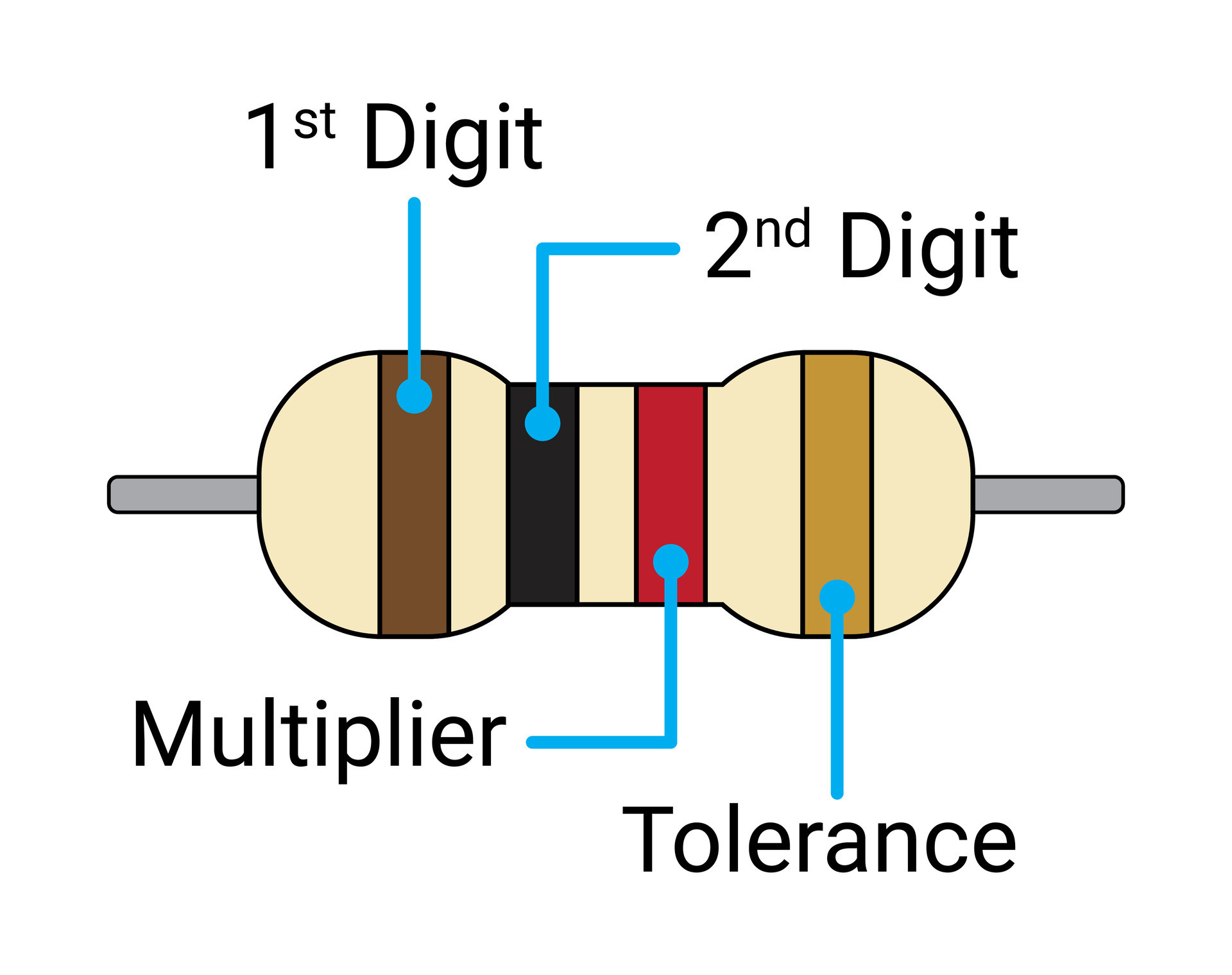

Basically, the four band resistor color code works on a system of significant digits, a multiplier, and a tolerance. Think of it like scientific notation but with a coat of paint. The first two bands represent the first two digits of the resistance value. The third band is the power of ten you multiply those digits by. The fourth band—usually spaced a little further apart from the others—is the tolerance.

Why the spacing matters

Look closely at a physical resistor. You'll notice three bands are bunched up together. The fourth one sits off by itself, looking a bit lonely. That gap is your "Start Here" sign. You read away from the bunched-up side. If you read it backward, you’ll end up thinking a $470\Omega$ resistor is actually some bizarre $2.7M\Omega$ component. That's a great way to make a circuit that does absolutely nothing.

Decoding the Rainbow

The colors follow the spectrum of a rainbow, mostly. Black is zero. Brown is one. Red is two. It goes on through violet, gray, and white. If you’ve ever taken an intro to engineering course, you’ve probably heard some questionable mnemonics to remember "Black, Brown, Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Violet, Gray, White."

Let's break down a real-world example. Imagine you have a resistor with the colors Yellow, Violet, Red, and Gold.

- Yellow is 4.

- Violet is 7.

- Red is the multiplier. In this case, it means $10^2$ (or 100).

- Gold is the tolerance, which is $\pm 5%$.

So, you take 47 and multiply it by 100. That gives you $4,700\Omega$, or $4.7k\Omega$. Because of that gold band, the actual resistance could be anywhere between $4,465\Omega$ and $4,935\Omega$. If your circuit is so sensitive that a $200\Omega$ swing ruins it, you’ve got bigger problems than just color codes.

The Multiplier is Where the Magic Happens

The third band is the one that trips everyone up. It’s the difference between a resistor that limits current for an LED and one that basically acts as a piece of wire.

If the third band is Black, you multiply by 1. So, Red-Violet-Black is $27\Omega$.

If it’s Brown, you multiply by 10. That same Red-Violet becomes $270\Omega$.

If it’s Orange, you’re multiplying by 1,000. Now you’re at $27k\Omega$.

It’s a logarithmic scale. A single color shift changes the value by an order of magnitude. This is why lighting is so important. Under a cheap LED shop light, a faded Red band can look suspiciously like Brown. If you’re ever in doubt, get a multimeter. Seriously. Even pros do it.

The Gold and Silver outliers

Sometimes the third band is Gold or Silver. This happens in low-resistance applications, like current sensing. Gold as a multiplier means you multiply by 0.1. Silver means 0.01. If you see Blue-Gray-Gold, you aren’t looking at a $6.8G\Omega$ monster; you’re looking at a $6.8\Omega$ resistor.

Tolerance: Why 5% is Usually "Good Enough"

The fourth band tells you how much the manufacturer is willing to lie to you.

Back in the day, a $20%$ tolerance was common (signified by no fourth band at all, though you rarely see that now). Today, Gold ($\pm 5%$) is the standard for general-purpose carbon film resistors. If you see a Silver fourth band, that’s $\pm 10%$.

Why does this matter?

Heat. Resistors generate heat as they dissipate power. As they get hot, their resistance shifts. A high-tolerance resistor is built to stay within a tighter "lane" even as things get sweaty inside the casing.

If you are working on high-fidelity audio gear or precision measurement tools, you’ll likely move away from the four band resistor color code and use five-band resistors instead. Those usually have a Brown tolerance band, which signifies $\pm 1%$. They are more stable, more precise, and frankly, a lot more annoying to read because the stripes are thinner.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

The biggest pitfall? Faded colors.

Old resistors, especially those pulled from vintage tube amps or 80s arcade boards, have lived a hard life. Heat cycles can bake the paint. A Red band that’s been simmering at $80^\circ C$ for twenty years might look like a sickly Orange or even a dull Brown.

🔗 Read more: How Is The Views Ratings Affecting Your Google Discover Reach?

Another one is the "Blue Body" confusion. Metal film resistors often have a blue body, while carbon film ones are beige or tan. The body color doesn't change the code, but it often indicates the type of resistor. Metal film (blue) usually uses five bands because they are higher precision. If you see four bands on a blue body, it’s often a specialized part or a high-wattage flameproof resistor.

The Physicality of the Four Band System

You'll mostly find these codes on axial-leaded resistors. These are the ones with wires coming out of both ends. Surface mount devices (SMD)—the tiny black specks on modern circuit boards—don’t use colors. They use tiny printed numbers like "103" (which is $10k\Omega$).

Why do we still use the four band resistor color code then?

Breadboarding. Prototyping. Education. When you’re pushing components into a plastic breadboard to see if an idea works, you can’t see tiny laser-etched numbers without a magnifying glass. The colors are visible from a distance. You can look at a messy desk and instantly spot the Red-Red-Brown ($220\Omega$) resistor you need for your LED.

Practical Steps for Mastering the Code

Don't try to memorize the whole chart in one night. It’s useless. Instead, focus on the "Big Three" multipliers: Brown ($x10$), Red ($x100$), and Orange ($x1,000$). These cover about $90%$ of what you'll use in hobbyist electronics.

Keep a reference card on your workbench. Every major component distributor like Digi-Key or Mouser gives these out for free, or you can find a high-res PDF online. Better yet, print one out and tape it to the lid of your component organizer.

When you buy resistors, keep them in their labeled baggies. The moment you dump a bunch of mixed resistors into a single bin, you've committed yourself to ten minutes of squinting and "Is that Orange or Yellow?" every time you want to build a circuit.

If you're serious about repairs, buy a component tester. These are cheap, $20$ handheld devices that you can clip a resistor into. It will tell you the exact resistance, bypassing the color code entirely. It’s a great way to double-check your eyes, especially as you get older and those tiny stripes start to blur together.

The four band resistor color code is a relic of a pre-digital age that is still remarkably efficient. It requires no power, no screen, and no software to read. Just a bit of light and a little bit of knowledge. Once you see the pattern, you can’t unsee it. You’ll start looking at circuit boards and seeing values instead of just pretty colors.

Stop guessing and start measuring. Grab a handful of resistors from your junk drawer and try to call out the value before you hit them with a multimeter. It’s the fastest way to turn this "secret language" into second nature.