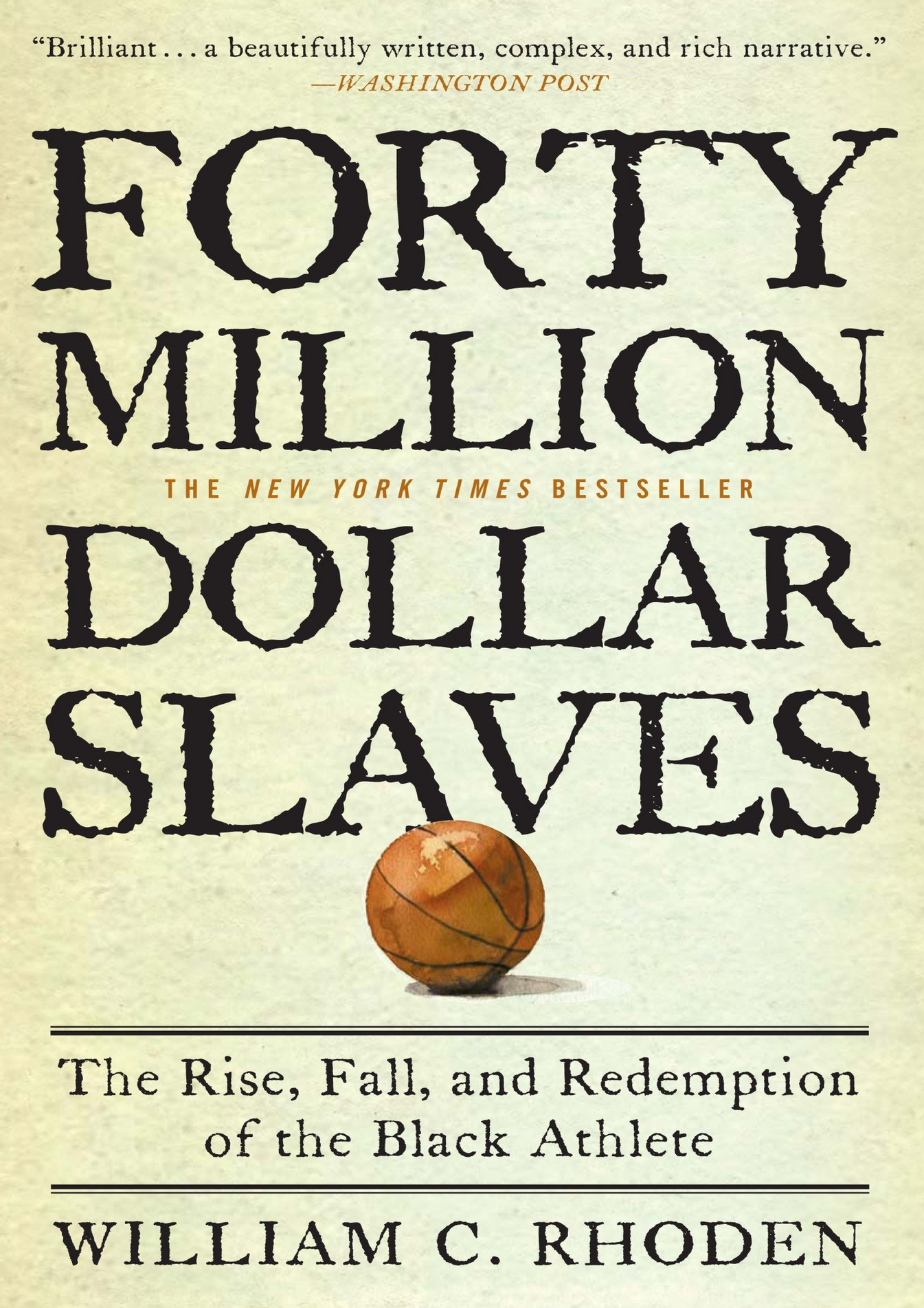

William C. Rhoden didn't just write a book about basketball and football. He wrote a manifesto that made a lot of powerful people in front offices very uncomfortable. When Forty Million Dollar Slaves hit the shelves in 2006, it felt like a grenade tossed into the center of the sports world's shiny, high-definition "diversity" narrative. Even today, nearly two decades later, the core arguments in the million dollar slaves book resonate every time a coach is fired or a player is told to "shut up and dribble."

The central tension is simple but brutal. You have these elite Black athletes who have reached the absolute pinnacle of wealth and fame. They’ve got the Mansions. The sneaker deals. The private jets. But Rhoden argues that, despite the tax bracket, the power dynamics haven't actually shifted since the days of the plantation. It’s a provocative, jarring comparison. Is it hyperbole? Maybe to some. But for anyone watching how the NFL or NBA actually operates behind the curtain, it’s a framework that’s hard to ignore.

The Plantation Model in Modern Arenas

Rhoden, a longtime New York Times columnist, traces a direct line from the "Jockey Syndrome"—the historical exclusion of Black athletes from horse racing once they became too successful—to the modern professional sports league. He isn’t saying LeBron James is literally a slave. That would be ridiculous. What he is saying is that the million dollar slaves book highlights a system where Black muscle is exploited for profit while the "conveyor belt" of talent is controlled entirely by white ownership.

Think about the scouting process. The Combine. Young men are poked, prodded, measured, and judged on physical specs. They are assets. Commodities.

The wealth is real, sure. But the control? That’s where things get murky. Rhoden argues that the industry is designed to keep athletes in a state of "permanent adolescence." You’re taken from a neighborhood, put into a high-major college program, and then dropped into a pro league where your every move is managed by agents, PR firms, and team owners. You're a millionaire who can’t choose his own boss for the first several years of a career. You have money, but you don't have the power to change the rules of the game you play.

🔗 Read more: Why Funny Fantasy Football Names Actually Win Leagues

Why the "Conveyor Belt" Theory Matters Now

One of the most haunting concepts in the million dollar slaves book is the idea of the "Conveyor Belt." It’s a mechanism that starts in the inner cities and rural South. It identifies talent early, isolates it, and grooms it for one specific purpose: generating revenue for institutions that the players will never own.

Look at the NIL (Name, Image, and Likeness) era in college sports. On the surface, it looks like progress. Players are finally getting paid! Finally, right? But Rhoden’s lens would suggest this is just a way to further professionalize the belt earlier. It doesn't give the players a seat at the Board of Trustees. It just gives them a bigger allowance while the university brand grows exponentially.

The "belt" works by stripping away a player's connection to their community. Once you're on it, your loyalty is to the brand, the league, and the sponsor. When an athlete speaks up about social issues—think Colin Kaepernick—the system tries to eject them. Why? Because the asset is malfunctioning. It’s no longer just a "unit of production." It’s becoming a person with agency, and the plantation model cannot handle agency.

The Problem of Integration Without Power

Rhoden makes a point that usually shocks people who grew up worshiping Jackie Robinson. He suggests that the integration of Major League Baseball was actually a "pyrrhic victory."

💡 You might also like: Heisman Trophy Nominees 2024: The Year the System Almost Broke

Before 1947, the Negro Leagues were thriving businesses. They had Black owners, Black managers, Black accountants, and Black bus drivers. It was an entire ecosystem. When Robinson went to the Dodgers, the talent followed him, but the infrastructure didn't. The Negro Leagues collapsed. The result? Black players were integrated into the field, but Black people were effectively shut out of the business side of sports for the next fifty years.

We traded ownership for participation.

Honestly, that’s the gut punch of the book. We celebrate the "firsts"—the first Black coach, the first Black GM—but we ignore the fact that the house they are walking into was built by someone else, and the deed is in someone else's name. In the NFL, we see this every January during the hiring cycle. The "Rooney Rule" exists because the natural inclination of the system is to exclude Black leadership, even when the labor force is 70% Black.

Beyond the Court: Actionable Insights for the Modern Fan

So, what do we actually do with this information? Reading the million dollar slaves book shouldn't just make you cynical about the Sunday night game. It should change how you consume the product.

📖 Related: When Was the MLS Founded? The Chaotic Truth About American Soccer's Rebirth

First, look at the coaching staff and the front office. When you hear a commentator talk about a player’s "natural athleticism" versus a coach’s "brilliant scheme," realize that’s the conveyor belt talking. It’s a subtle way of reinforcing the idea that the labor is physical (Black) and the management is intellectual (White).

Second, support athlete-led ventures that prioritize ownership. When players like Kevin Durant or LeBron James start their own production companies or investment firms, they are attempting to break the cycle Rhoden described. They are trying to own the "conveyor belt" rather than just riding it.

Real-World Steps for Change

- Scrutinize the Pipeline: Pay attention to how your local college or pro teams treat athletes’ education and post-career transitions. Is it a four-year pump-and-dump, or is there real investment in the human being?

- Follow the Money: Look at where league profits go. Are they being reinvested in the communities that produce the talent, or are they just padding the pockets of billionaires who threaten to move the team if they don't get a tax-funded stadium?

- Demand Diverse Leadership: It’s not enough to have Black stars on the jersey. True equity in sports looks like diversity in the owner's box and the league offices.

Rhoden’s work is uncomfortable because it demands that we stop looking at sports as a pure meritocracy. It’s a business. It’s a power structure. And as long as the people on the field have no say in how the league is run, the "slave" metaphor—no matter how many millions are involved—will continue to haunt the American stadium.

The next time you watch a draft, don't just look at the 40-yard dash times. Look at the people holding the stopwatches. That’s where the real story of the million dollar slaves book lives. It’s in the gap between the talent and the power.

To truly understand the modern landscape, you've got to look at the history of the "Jockey Syndrome" and how it repeats. Start by researching the history of the Negro Leagues not as a "precursor" to MLB, but as a lost era of Black economic independence. Compare that to the current push for HBCU sports prominence. The goal shouldn't just be to play in the big leagues; the goal, as Rhoden suggests, is to build leagues of our own.