You probably think paying taxes is a once-a-year headache. Wrong. For a massive chunk of the population—freelancers, side-hustlers, investors, and small business owners—the IRS expects a check every three months. If you’re waiting until April 15th to settle up, you’re basically asking the government to slap an underpayment penalty on your account. It’s annoying. It’s expensive. Honestly, it's totally avoidable if you understand how form 1040 estimated tax actually works.

Uncle Sam operates on a "pay-as-you-go" system. When you're a W-2 employee, your boss handles the math and sends a slice of your paycheck to the treasury before you even see it. But when you’re the boss, or when your money comes from dividends or a rental property, nobody is doing that dirty work for you. You have to be your own payroll department. If you don't, you end up in a situation where you owe thousands in April plus a "failure to pay" penalty that feels like a kick in the teeth.

The 1040-ES Reality Check

Let’s be real: nobody likes filling out extra paperwork. But form 1040 estimated tax (technically Form 1040-ES) is the document that keeps you out of the IRS doghouse. You aren't actually filing this form in the traditional sense; it’s more of a worksheet and a set of payment vouchers. You calculate what you think you'll owe for the year, divide it by four, and send it in by the deadlines.

Who actually needs to do this? The rule of thumb is simple. If you expect to owe $1,000 or more when you file your return, you need to make estimated payments.

There are safe harbors, though. You generally won't get penalized if your total withholding and timely estimated payments equal at least 90% of the tax on your current year's return or 100% of the tax shown on your return for the prior year. If your adjusted gross income (AGI) is over $150,000, that 100% jumps to 110%. It’s a bit of a math puzzle, but it’s the only way to shield yourself from the IRS's interest charges.

When the Money is Actually Due

The "quarterly" schedule is a total lie. It’s not actually every three months. Look at the dates:

💡 You might also like: 25 Pounds in USD: What You’re Actually Paying After the Hidden Fees

- April 15 (Q1)

- June 15 (Q2 - Only two months later!)

- September 15 (Q3 - Three months later)

- January 15 of the following year (Q4 - Four months later)

If those dates fall on a weekend or holiday, you get until the next business day. But missing them by even a few days can trigger interest. The IRS doesn't care if your clients haven't paid you yet. They want their cut based on when the income was "earned."

Why Most People Mess This Up

Most people wait until the end of the year to look at their books. That's a disaster. If your income swings wildly—maybe you’re a Realtor who closed three deals in May and nothing in November—you might benefit from the "annualized income installment method." It’s a nightmare of a worksheet (found in Publication 505), but it allows you to pay more when you make more and less when you’re broke.

Without this, the IRS assumes you earned your money evenly throughout the year. If you make $100k in December and pay the tax in January, they might still try to penalize you for not paying "enough" in April. You have to prove to them when the money actually hit your bank account.

The Self-Employment Tax Trap

If you’re new to the 1099 life, the biggest shock isn't the income tax. It's the self-employment tax. When you work for a company, they pay half of your Social Security and Medicare taxes ($15.3%$ total, usually split $7.65%$ each). When you’re self-employed, you pay both halves. That’s a $15.3%$ surcharge on top of your standard income tax bracket.

When calculating your form 1040 estimated tax, you must include this. If you’re just estimating based on your old W-2 tax rate, you’re going to be short. Way short.

📖 Related: 156 Canadian to US Dollars: Why the Rate is Shifting Right Now

Real World Example: The Consultant's Mistake

Take "Sarah," a freelance graphic designer who transitioned from a $80k salary to $120k in freelance contracts. In her first year, she figured she’d just save $20k for tax season. She didn't realize that between her higher income bracket and the self-employment tax, her actual liability was closer to $35k.

Because she didn't send in quarterly payments, she didn't just owe the $35k in April; she owed an additional $1,200 in underpayment penalties. The IRS viewed her as having "borrowed" that money from the government throughout the year.

How to Calculate Without Losing Your Mind

You don't need a PhD in accounting, but you do need last year's tax return. That is your North Star. If you use the "100% of last year's tax" rule, you are safe from penalties even if you make a million dollars this year. It's the easiest way to sleep at night.

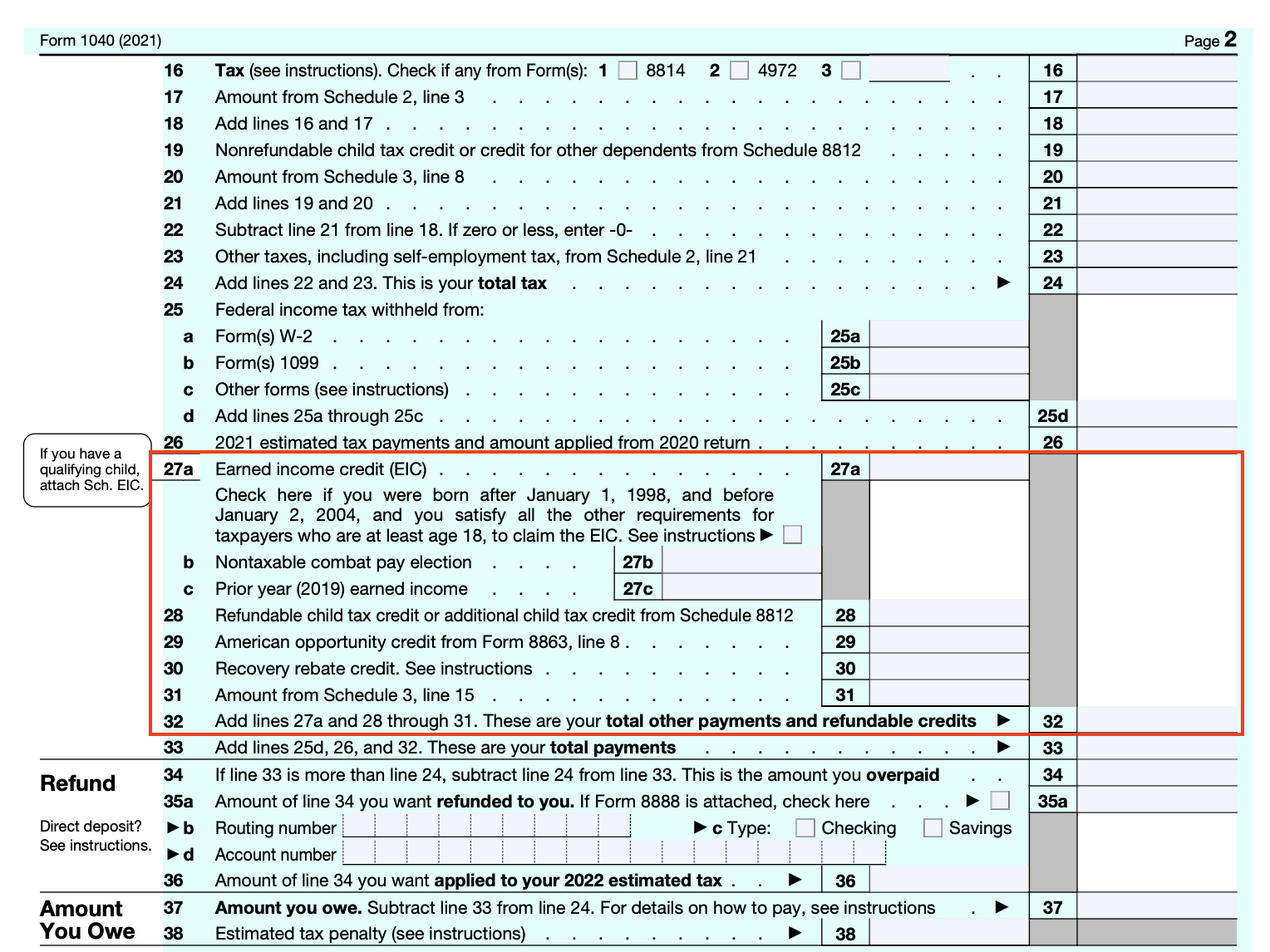

- Find the "Total Tax" line on your previous 1040.

- Divide that number by four.

- Pay that amount every quarter.

- If you end up making way more money, just be prepared to pay the difference in April—but you won't owe penalties.

Of course, if your income dropped, don't overpay. Use the 1040-ES worksheet to estimate your current year's AGI, deductions, and credits. Just be conservative. It’s better to get a small refund than to realize in January that you’ve spent the IRS's money on a new MacBook.

Where to Send the Money

Stop using paper checks. Seriously. The IRS is buried in paper. Use IRS Direct Pay. It’s free, it’s instant, and you get a digital receipt. Select "Estimated Tax" as the reason for payment and "1040-ES" as the form. If you use the Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS), you can even schedule all four payments at the start of the year and forget about it.

👉 See also: 1 US Dollar to China Yuan: Why the Exchange Rate Rarely Tells the Whole Story

Common Misconceptions About 1040-ES

Some people think if they have a "day job" with withholding, they don't need to pay estimated taxes on their side business. That’s only true if your day job withholding is high enough to cover the tax on your side hustle. A pro tip? Instead of sending quarterly checks for your side gig, just go to your HR department and increase your W-2 withholding. It counts as being paid "evenly" throughout the year, which can actually bail you out if you forgot to pay estimates earlier in the year.

Another myth: "I didn't make a profit this quarter, so I don't owe."

Taxes are cumulative. If you made a killing in Q1 but lost money in Q2, you still owe for what you made in Q1. You can't just ignore the deadline because your bank account looks low today.

Technical Nuances for High Earners

If you’re dealing with the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) or the Additional Medicare Tax, your form 1040 estimated tax calculations get hairier. These kick in at certain income thresholds (like $200k for singles or $250k for married filing jointly). These aren't just "income taxes"—they are surtaxes. If you don't account for that extra $0.9%$ or $3.8%$, you'll find yourself in the underpayment zone very quickly.

Also, don't forget state taxes. Most states that have income tax require their own version of estimated payments. If you’re in California or New York, the state is arguably more aggressive about their quarterly cuts than the Feds are.

Actionable Steps to Stay Compliant

- Open a separate tax savings account. Every time a client pays you, move 25-30% of that check immediately. Don't touch it. It’s not your money; you’re just holding it for the Treasury.

- Use the Safe Harbor Rule. If you’re unsure, just pay 100% (or 110% for high earners) of last year’s tax. It’s the simplest way to avoid the penalty.

- Track your expenses monthly. Don't wait until tax season to realize you have $10,000 in deductible business expenses. Knowing your net profit in real-time makes your 1040-ES estimates much more accurate.

- Check the calendar. Set recurring calendar alerts for April 15, June 15, September 15, and January 15. Give yourself a one-week lead time so you aren't scrambling to find cash.

- Adjust for life changes. Got married? Had a kid? Sold a house? These things change your tax liability. Re-run your 1040-ES worksheet after any major life event.

The IRS isn't trying to bankrupt you with estimated taxes—they just want their money as you earn it. If you treat tax payments as a monthly or quarterly utility bill rather than a once-a-year catastrophe, the entire process becomes a non-event. It’s just the cost of doing business.