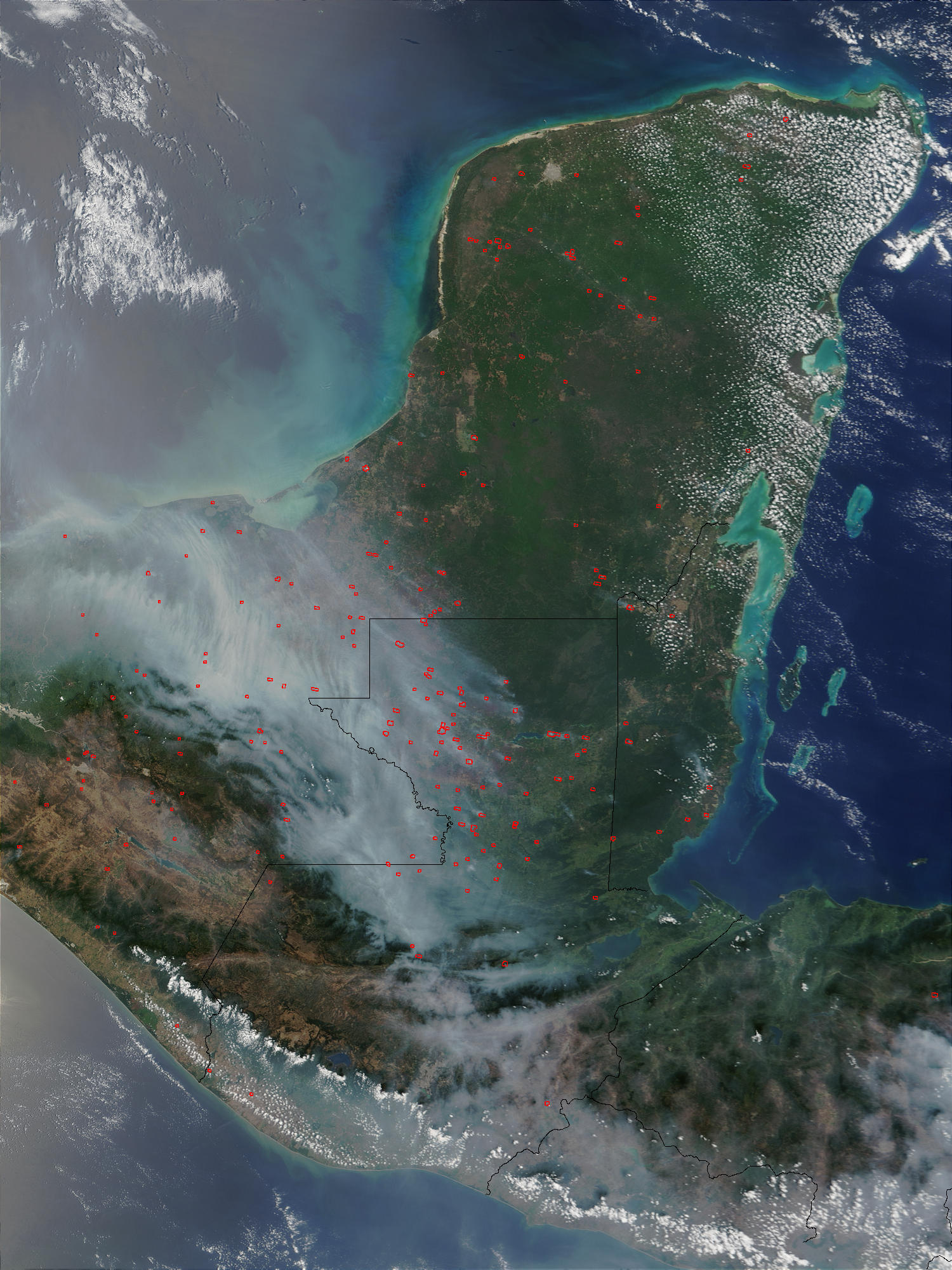

Smoke doesn't care about borders. Last spring, you might have seen those hazy, orange-tinted sunsets in Texas or even as far north as Chicago and thought it was just local pollution. It wasn't. Much of that grit was drifting up from the Sierra Madre. Forest fires in Mexico have become a seasonal reality that feels increasingly like an escaped monster. Honestly, it’s not just about "hot weather" anymore. We are looking at a messy intersection of climate shifts, old-school farming habits, and a massive budget crunch that has left firefighters bringing shovels to a blowtorch fight.

It’s getting worse.

In 2023, the National Forestry Commission (CONAFOR) reported over 7,000 fires. That sounds like a lot until you look at the acreage: over a million hectares burned. To put that in perspective, that’s an area roughly the size of Lebanon turned to ash in a single year. People often think of Mexico as just tropical beaches or deserts, but the country is actually home to some of the most biodiverse temperate and cloud forests on the planet. When those go up, we aren't just losing trees. We’re losing the lungs of North America.

The Brutal Reality of the Estiaje Season

Mexico has a specific time of year called estiaje. It’s the dry season. Usually, it runs from January to June, but lately, the rains are late. Or they just don't show up at all.

When the moisture drops, the forests become a tinderbox. The state of México, Jalisco, and Chiapas usually get hit the hardest. Why? Because that’s where the people are. See, most people assume these fires are started by lightning. In the Western U.S., that’s often true. In Mexico? Not even close. Almost 90% of forest fires in Mexico are caused by human activity.

Sometimes it’s a campfire that wasn't put out. More often, it’s roza, tumba y quema—the traditional slash-and-burn agriculture. Farmers burn their fields to prep for the next planting season. It’s been done for centuries. But when the humidity is at 10% and the wind starts howling at 40 kilometers per hour, a controlled burn becomes a landscape-level disaster in about six minutes.

The heat is different now, too.

👉 See also: The Ethical Maze of Airplane Crash Victim Photos: Why We Look and What it Costs

Climate change isn't just a buzzword here; it’s a physical weight. Prolonged droughts, fueled by El Niño cycles, have sucked the life out of the soil. When a fire hits a drought-stricken pine forest in Michoacán, it doesn't just crawl along the ground. It "crowns." It jumps from treetop to treetop, moving faster than a person can run.

Why the 2024 Season Changed the Conversation

Last year was a wake-up call. We saw fires breaking out in places that are traditionally too damp to burn. The "High Peaks" region and the cloud forests of Veracruz saw smoke. Even the outskirts of Mexico City were choked for weeks.

The government’s response has been... complicated.

There’s no polite way to say it: budget cuts have hurt. CONAFOR has seen its funding slashed significantly over the last few years. When you have fewer boots on the ground and fewer helicopters in the air, you can't jump on a "smoke report" immediately. You wait. And while you wait, the fire grows. Local communities have stepped up, often fighting flames with nothing but wet blankets and handheld sprayers. It’s heroic, but it’s also terrifyingly dangerous.

The Economics of the Burn

It’s easy to blame a farmer for starting a fire. It’s harder to address why they’re burning in the first place. For many in rural Oaxaca or Guerrero, fire is the only "fertilizer" they can afford. They need to clear land for corn or cattle.

Then there’s the darker side: land-use change.

✨ Don't miss: The Brutal Reality of the Russian Mail Order Bride Locked in Basement Headlines

In some parts of Mexico, there is a weird legal loophole. You can’t legally cut down a forest to build a resort or plant an avocado orchard. But, if the forest "accidentally" burns down? Well, then the land is suddenly classified as "degraded." Once it's degraded, getting a permit to turn it into a profitable Hass avocado farm becomes much easier. This "fire for hire" mentality is a massive, often unspoken driver of forest fires in Mexico. It's an economic incentive to destroy the environment.

We also have to talk about the "Brigadistas."

These are the frontline forest firefighters. Many are volunteers or seasonal workers. They are the ones walking miles into the mountains with 20 kilograms of gear on their backs. They deserve better equipment. Honestly, they deserve better pay. In many states, the equipment they're using is decades old. If you want to stop the smoke from reaching Texas or California, the solution starts with a shovel in the hands of a well-paid Brigadista in Jalisco.

Beyond the Smoke: What We Lose

When a forest burns in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, it’s not just a local tragedy. It’s a global one. Those Oyamel fir trees are the only place those butterflies can winter. If those trees go, the migration ends. Period.

- Water Security: Forests act like sponges. They hold the water that eventually feeds the aquifers for cities like Guadalajara and Mexico City. No trees? No water.

- Soil Erosion: Once the roots are dead, the next big rain washes the mountain into the valley. We see mudslides that bury entire villages.

- Air Quality: Mexico City already struggles with geography. It’s a bowl. When the surrounding mountains burn, the smoke gets trapped. Respiratory hospitalizations spike by 30% during heavy fire weeks.

Turning the Tide: What’s Actually Working

It’s not all doom. There are some incredibly smart things happening on the ground.

Community-led forestry is the biggest win. In places like Quintana Roo and Oaxaca, local indigenous communities have been given the rights to manage their forests. Because they make a living from sustainable logging or eco-tourism, they have a vested interest in not letting it burn. They patrol. They create firebreaks. They catch small blazes before they become "megafires."

🔗 Read more: The Battle of the Chesapeake: Why Washington Should Have Lost

Technological shifts are helping, too.

The use of satellite monitoring has gotten much more precise. We can now see a "heat signature" from space almost the moment a fire starts. The challenge isn't seeing the fire; it's getting the resources to the GPS coordinates fast enough.

What You Can Actually Do About It

If you’re living in or visiting Mexico, the "Leave No Trace" rules aren't just suggestions. They are survival tactics.

- Check the Sky: If you’re hiking during the spring, check the CONAFOR daily fire map. If it’s a high-wind day, don't even think about lighting a stove.

- Support Local Conservation: Organizations like Pronatura work directly on reforestation and fire prevention. They need the help that the federal budget is currently missing.

- Be a Conscious Consumer: This sounds disconnected, but it’s not. Demand transparency in where your avocados and limes come from. If they’re grown on recently "burned" forest land, that's a problem.

- Report Early: If you see smoke in the mountains, don't assume someone else called it in. In Mexico, you can call 800-737-00-00 (800-INCENDIO) to report a fire directly to the authorities.

A Shift in Perspective

We have to stop viewing forest fires in Mexico as an inevitable natural disaster. They are a social and economic issue. Nature knows how to handle fire; it has for millions of years. But it doesn't know how to handle fire at this frequency and this intensity.

The goal isn't just putting out flames. It’s changing the value of a standing tree compared to a burned one.

Next Steps for Action:

For those looking to get involved or stay informed, your first move should be following the official CONAFOR Twitter or Facebook feeds for real-time alerts. If you are a landowner, look into the "Payment for Environmental Services" (PSA) programs which provide financial incentives for keeping forests intact. Finally, if you're traveling through rural Mexico during the dry season, avoid using any open flames and strictly adhere to local fire bans—your caution is the most effective firefighting tool we have.