You’re standing at the top of a steep driveway on a rainy Tuesday. Your car starts to roll. In that split second, you aren’t thinking about Sir Isaac Newton or the Greek letter theta ($\theta$), but your car is definitely feeling them. It’s physics. Specifically, it’s the weird way forces on an incline behave compared to when you’re just sitting on flat ground. When things are level, gravity pulls straight down, and the ground pushes straight up. Simple. But tilt that surface even a few degrees, and suddenly gravity decides to split its personality.

Gravity is the ultimate constant, yet on a slope, it becomes a bit of a trickster.

If you’ve ever tried to push a couch up a ramp, you know it feels heavier than it should, yet somehow easier than lifting it straight up. That’s because the incline is doing some of the work for you, but it’s also demanding a tax in the form of friction. Honestly, understanding how these vectors interact is the difference between a successful engineering project and a literal car wreck.

💡 You might also like: The Symbol of Beta Radiation: Why This Little Greek Letter Matters More Than You Think

The Geometry of the Slide

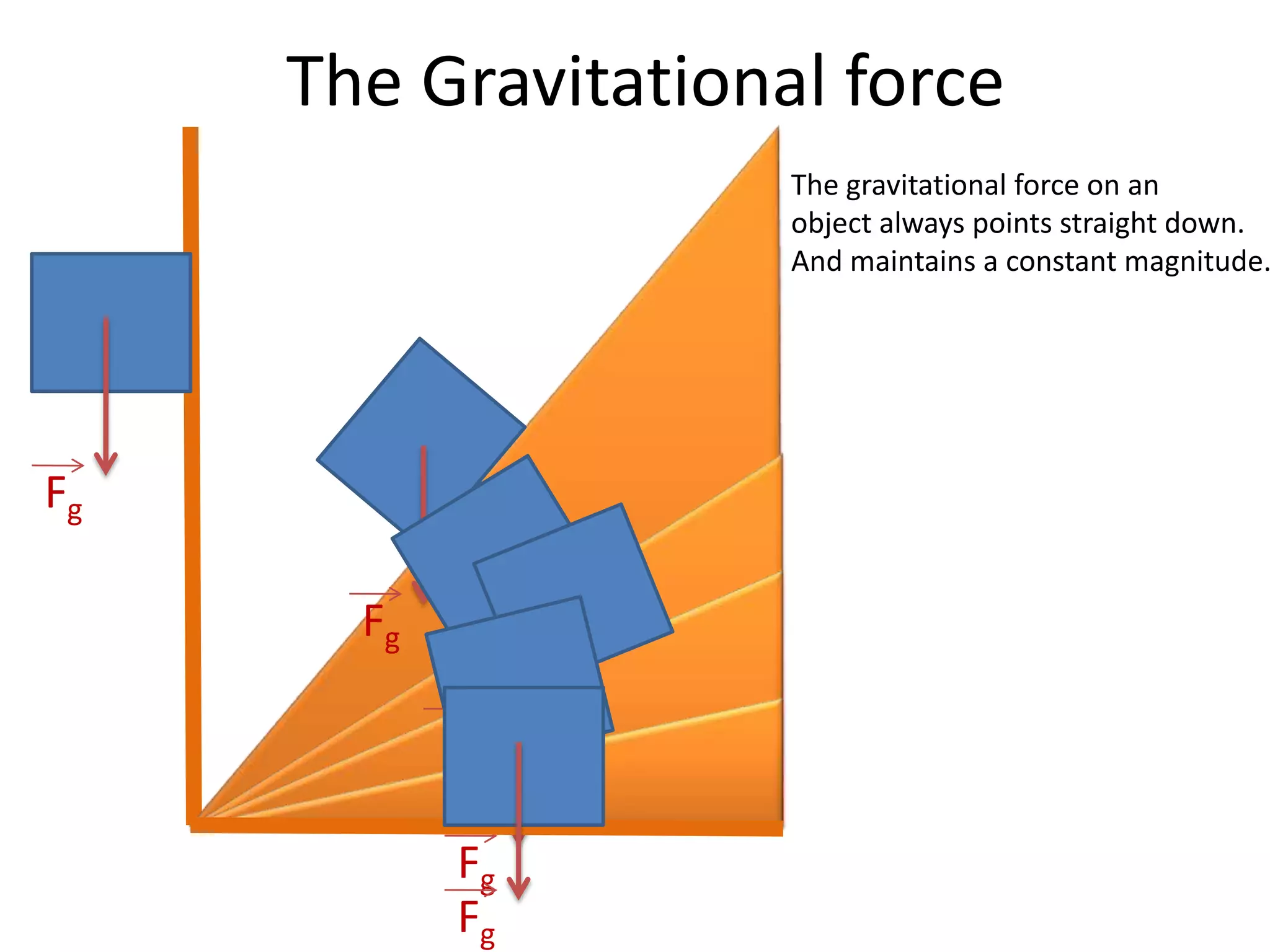

Gravity doesn't care about your ramp. It always points toward the center of the Earth. Period. But when an object sits on a slope, that downward pull gets "resolved" into two different components. Think of it like a budget being split between two departments. One part of the force presses the object into the hill—we call this the perpendicular component. The other part tries to accelerate the object down the hill—the parallel component.

The math isn't just for textbooks. It’s the reason why roads in the Rockies have "runaway truck ramps." Engineers have to calculate exactly how much of a semi-truck’s weight is being converted into downhill speed. The formula for the force pulling an object down is $F = m g \sin(\theta)$. As the angle ($\theta$) gets steeper, the sine value increases. At 90 degrees, you're just in freefall.

But what about the part pressing down? That’s $F = m g \cos(\theta)$. This component is what creates the "Normal Force." It’s basically how hard the surface is pushing back. If the surface didn't push back, you’d just sink through the ramp like it was made of shadows. This Normal Force is the gatekeeper of friction. No squeeze, no grip.

Friction: The Unsung Hero (and Villain)

Friction is kinda fickle. It depends almost entirely on two things: what the surfaces are made of and how hard they are being pressed together. This is where people usually get tripped up with forces on an incline. On a flat surface, the Normal Force is equal to the object's full weight. On a hill, the Normal Force is reduced because some of that gravity is busy trying to make the object slide.

- Static friction is what keeps your car from moving when the parking brake is on.

- Kinetic friction is what heats up your brake pads as you slide down a mountain pass.

- The "Coefficient of Friction" ($\mu$) is a decimal that describes the "stickiness" of the interface.

Actually, there’s a sweet spot called the "angle of repose." It’s the steepest angle a pile of material—like sand or grain—can maintain without sliding. If you exceed it, the parallel force of gravity overcomes the maximum static friction. Avalanches happen exactly this way. A layer of snow loses its grip, the parallel force wins the tug-of-war, and thousands of tons of ice start accelerating.

It’s not just about weight, though. A common misconception is that heavier objects slide faster. In a vacuum, sure, everything falls at the same rate. But on a ramp, the mass ($m$) actually cancels out in the basic acceleration equation ($a = g \sin(\theta) - \mu g \cos(\theta)$). If you ignore air resistance, a bowling ball and a marble should race down a slide at the same speed.

Why Inclines Revolutionized Technology

We’ve been using the "inclined plane" since the dawn of civilization. It’s one of the six simple machines. Think about the Great Pyramid of Giza. There is no way the ancient Egyptians were dead-lifting 2.5-ton limestone blocks. They used ramps. By increasing the distance the block had to travel, they decreased the amount of force needed at any single moment.

It’s a trade-off. You push with less force, but you push for a longer time. This is "Mechanical Advantage."

Modern tech uses this everywhere. A screw is just an inclined plane wrapped around a cylinder. A wedge (like an axe or a doorstop) is just two inclined planes joined back-to-back. Even the fans in your computer use tilted blades to "slide" air molecules forward. Without the physics of slanted surfaces, our mechanical world would basically grind to a halt.

The Problem with Real-World Variables

In a physics lab, we pretend there’s no air and the ramp is perfectly smooth. Real life is messier. You have to account for:

- Air Drag: This becomes massive at high speeds (like a skier on a downhill run).

- Surface Deformation: If the ramp is soft, like mud, the object sinks, changing the "Normal Force" vectors.

- Rolling Resistance: Wheels aren't perfect. They squish a little, which creates a tiny hill in front of the tire that it's constantly trying to climb.

Dr. Richard Feynman used to talk about how the complexity of the world is hidden in these "simple" interactions. You think you’re just looking at a box on a board, but you’re actually looking at a complex dance of electromagnetic forces between atoms (friction) and the warping of spacetime (gravity).

How to Calculate it Yourself

If you’re trying to move something heavy or just curious why your skateboard behaves the way it does, you can do some quick "back of the envelope" math.

First, find the angle. Most smartphones have a level app that gives you the degrees.

Second, know your mass in kilograms.

Third, remember that gravity on Earth is roughly $9.8$ $m/s^2$.

If you want to know if something will slide, you need to compare the "Downhill Force" to the "Frictional Force."

Downhill = $m \cdot g \cdot \sin(\theta)$

Max Friction = $\mu \cdot m \cdot g \cdot \cos(\theta)$

If the first number is bigger than the second, it’s going to move. If you're building a wheelchair ramp, the ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) actually mandates a specific ratio—usually 1:12. That’s about 4.8 degrees. Any steeper, and the force required to push the chair becomes dangerous for most users.

Misconceptions That Can Be Dangerous

One big mistake people make is thinking that more weight always means more grip. While more weight does increase the Normal Force (which increases friction), it also increases the Downhill Force by the exact same proportion. If a light car slides on an icy hill, a heavy truck will likely slide too. The only thing that really helps is changing the "Coefficient of Friction"—like putting chains on tires or throwing sand on the ice.

Another weird one? The "Normal Force" isn't always "up." It’s "perpendicular." If you’re on a 45-degree slope, the ground is pushing you sideways as much as it’s pushing you up. This is why it feels so weird on your ankles to walk along the side of a steep hill. Your bones are dealing with shear forces they aren't used to.

Practical Steps for Dealing with Inclines

If you're working with forces on an incline in a practical setting—whether it's landscaping, moving furniture, or designing a DIY skate ramp—here’s what you actually need to do:

- Measure the Angle Twice: A difference of 5 degrees can double the acceleration force on an object. Don't eyeball it. Use a digital protractor or a level app.

- Check the Surface Material: If you’re moving something heavy up a wooden ramp, a little bit of sawdust can act like ball bearings, drastically dropping your friction coefficient ($\mu$). Clean your surfaces.

- Increase the Normal Force if You’re Slipping: If you can't get traction on a hill, you need to "bite" into the surface. This is why hikers use trekking poles. It adds a vertical force component that increases the effective friction.

- Use the Mechanical Advantage: If a ramp is too steep to push a load up, make the ramp longer. Doubling the length of the ramp (while keeping the height the same) effectively halves the force you need to exert.

- Secure the Base: Remember that the ramp itself wants to slide backward as you push the object forward (Newton’s Third Law). Always anchor your incline at the bottom.

Understanding these forces isn't just for passing a high school physics quiz. It's how you stay safe when the world isn't level. Whether it’s choosing the right shoes for a hike or figuring out if your truck can pull a trailer up a mountain pass, the math is always running in the background. Pay attention to it.