You’re standing on a scale. It’s Monday morning. The number that pops up makes you cringe, but honestly, that number is a lie. Well, it's a half-truth. What that scale is actually measuring isn't just "you"—it's a specific interaction between your mass and the giant rock we live on. This is where the force formula with gravity stops being a boring high school physics chapter and starts being the reason you don't float into the stratosphere while eating breakfast.

Gravity is sticky. It’s weak compared to magnets, but it’s relentless. When we talk about force in a general sense, we usually point to Newton’s Second Law. You know the one: $F = ma$. Force equals mass times acceleration. Simple. But when gravity enters the chat, that "a" (acceleration) gets replaced by a very specific, very stubborn constant.

The basic force formula with gravity explained

Basically, the force of gravity—which we usually just call weight—is calculated by multiplying an object's mass by the acceleration due to gravity. On Earth, that acceleration is roughly $9.8 \text{ m/s}^2$.

The formula looks like this:

$$F_g = mg$$

Here’s the nuance: mass and weight are not the same things. If you take a 70kg human and teleport them to the Moon, their mass is still 70kg. They haven't lost any molecules. But their weight? It plummets. Because the "g" on the Moon is only about $1.6 \text{ m/s}^2$. You’re the same person, just with a different force profile.

Why does this matter? Because every piece of technology we build, from the elevator in your office to the Falcon 9 rockets landing upright, relies on getting this math perfect. If an engineer forgets that $g$ isn't a universal constant, things break. People fall. Satellites miss their orbits.

📖 Related: Where was Microsoft started? The New Mexico desert story you probably forgot

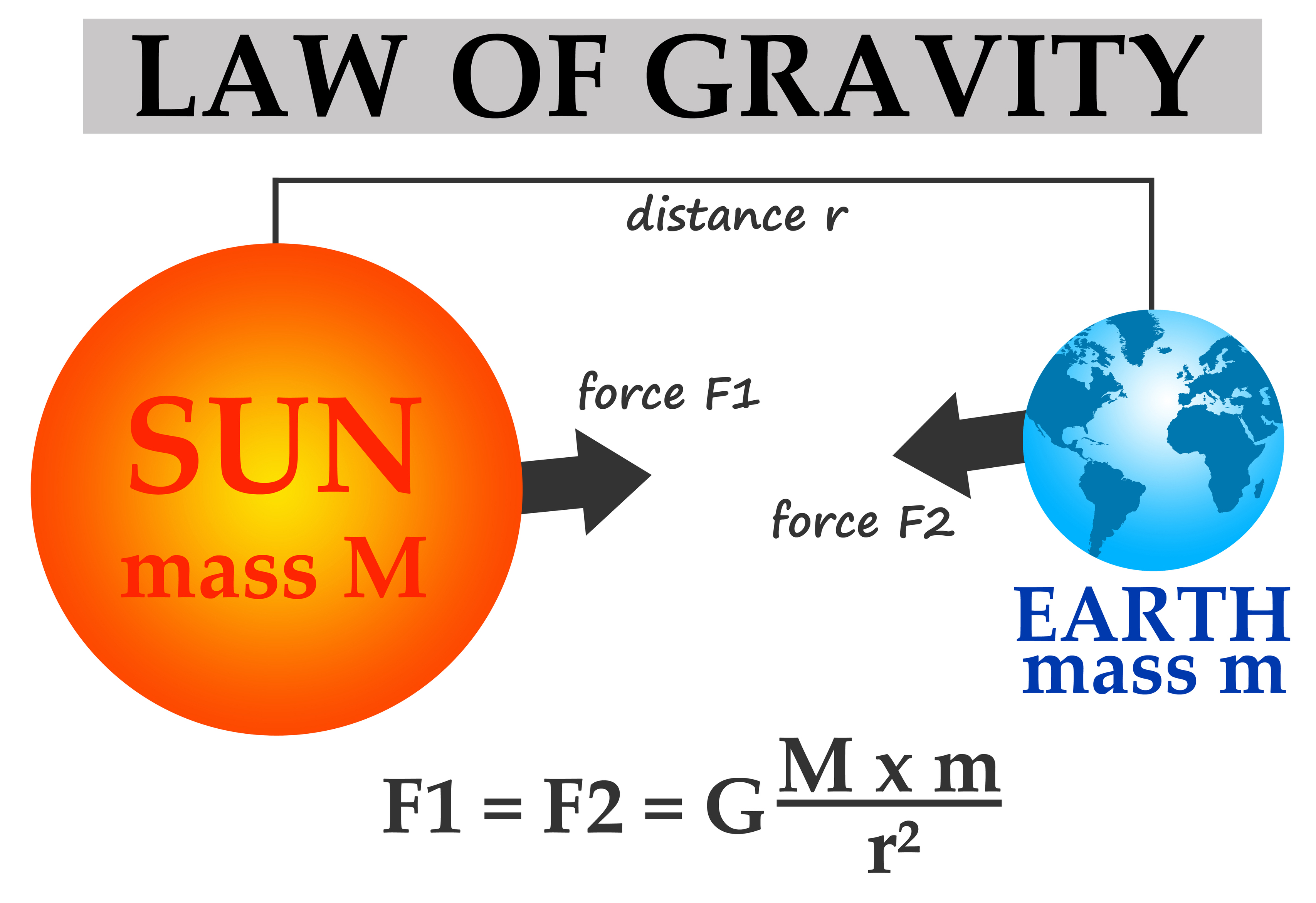

The Inverse Square Law: It’s not just a flat number

We often treat gravity as a constant $9.8$, but that’s a simplification for people who don't want to do hard math. In reality, gravity changes based on how far you are from the center of the Earth. This is governed by Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation.

$$F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}$$

Look at that $r^2$ at the bottom. That’s the distance between the centers of two objects. As you get further away, the force doesn't just drop; it drops exponentially. If you double your distance from Earth's center, you don't feel half the gravity. You feel one-fourth.

This is why astronauts on the International Space Station (ISS) look weightless. A lot of people think there’s "no gravity" in space. That’s totally wrong. At the altitude of the ISS, gravity is still about 90% as strong as it is on the ground. The reason they float is that they are in a constant state of freefall, moving sideways fast enough that they keep "missing" the Earth as they fall toward it. They are living inside a continuous force formula with gravity calculation.

Real-world deviations you can actually measure

Did you know you weigh less at the equator than at the poles? It’s true.

Earth isn't a perfect sphere; it's an oblate spheroid. It bulges at the middle because it's spinning. When you stand at the equator, you’re further from the Earth’s center of mass than when you’re at the North Pole. Plus, the centrifugal force from the Earth's rotation pushes you "out" slightly.

If you're a professional weightlifter trying to break a world record, you'd technically have an easier time doing it in Quito, Ecuador, than in Oslo, Norway. We’re talking about fractions of a percent, but in high-stakes physics and commerce, those fractions are huge.

Gravity’s role in modern tech and engineering

We use the force formula with gravity to calibrate everything. Think about your phone. It has an accelerometer. That tiny chip is constantly measuring the force of gravity to figure out which way is "down" so it can rotate your screen.

- Civil Engineering: When building a skyscraper like the Burj Khalifa, engineers don't just calculate the weight of the steel. They have to account for "live loads" (people, furniture) and how gravity interacts with wind shear.

- Aerospace: Every gram of fuel on a plane is a battle against $F = mg$. If the plane is too heavy, the lift generated by the wings won't overcome the gravitational force pulling it down.

- Hydraulics: Water towers use gravity to create pressure. By placing a tank high up, they use the force of gravity on the mass of the water to push it through the pipes into your showerhead. No pumps needed for the actual delivery—just raw physics.

Common misconceptions about falling objects

Galileo famously (perhaps apocryphally) dropped two balls of different masses from the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Most people at the time thought the heavier one would hit first. They were wrong.

If you ignore air resistance, everything falls at the same rate. A hammer and a feather fall at the exact same speed in a vacuum. This was famously proven on the Moon by Apollo 15 astronaut David Scott. Because the "m" in $F=ma$ (inertia) and the "m" in $F=mg$ (gravitational mass) cancel each other out, the acceleration remains $g$ regardless of how heavy the object is.

$$ma = mg \implies a = g$$

It’s elegant. It’s weird. It’s the reason a bowling ball and a marble dropped in a vacuum chamber hit the floor at the same millisecond.

How to calculate force in your own life

Want to get practical? You can calculate the force required to lift something quite easily. Let's say you're at the gym. You're deadlifting 100kg.

To just hold that bar still, you have to exert a force equal to the gravitational pull on it:

$100 \text{ kg} \times 9.8 \text{ m/s}^2 = 980 \text{ Newtons}$.

If you want to actually move it upward, you have to exert more than 980 Newtons. If you only exert 980, the bar stays exactly where it is (or continues moving at a constant velocity if it was already moving). To accelerate it, you need to overcome that baseline force. This is why the first inch of a lift feels the hardest. You're fighting the transition from static to dynamic force.

The limits of Newton: Enter Einstein

For most of us, $F = mg$ is the end of the story. But if you’re working with GPS satellites or black holes, Newton’s formula starts to fail. Albert Einstein realized that gravity isn't really a "force" in the way a shove is a force. Instead, mass warps the fabric of space-time.

Think of a trampoline with a bowling ball in the middle. The dip in the fabric is gravity. When you move, you’re just following the curves. For GPS satellites to work, they have to account for General Relativity because gravity is slightly weaker up there, and time actually moves at a different rate. If we used the standard force formula with gravity without Einstein’s corrections, your Google Maps would be off by several kilometers within a single day.

Practical Steps for Applying Force Logic

If you're trying to solve a physics problem or just want to understand the world better, follow these steps to use the formula correctly:

Identify the Mass in Kilograms

Scales often give you pounds, but physics happens in kilograms. Divide pounds by 2.2 to get your mass. This is your "resistance to change."

Determine Your Local Gravity

Usually, $9.8$ is fine. But if you're doing high-precision work or you're on another planet (lucky you), you need the specific gravitational constant for that location.

Account for Other Forces

Gravity never acts alone. There's friction, air resistance, and normal force (the ground pushing back). If you're sliding down a hill, you have to use trigonometry to find the "component" of gravity pulling you down the slope versus the part pulling you into the dirt.

Calculate the Weight (Force)

Multiply your mass by $g$. The result is in Newtons. If you want to know how much work you're doing, multiply that force by the distance you move the object.

Understanding the force formula with gravity isn't just about passing a test; it’s about recognizing the invisible tethers that keep the moon in orbit and your coffee in its cup. It is the most fundamental "rule" of our physical existence. Next time you feel heavy after a big meal, just remember: you aren't fat, you're just experiencing a highly effective local gravitational field.