It was cold. That’s the first thing everyone remembers about the story. In the winter of 2006, a guy named Justin Vernon—broken-hearted, sick with mononucleosis, and reeling from the breakup of his band DeYarmond Edison—drove to his father’s hunting cabin in Medford, Wisconsin. He wasn’t there to change music. Honestly, he was just there to hide. He stayed for three months. He chopped wood. He looked at the snow. He recorded sounds.

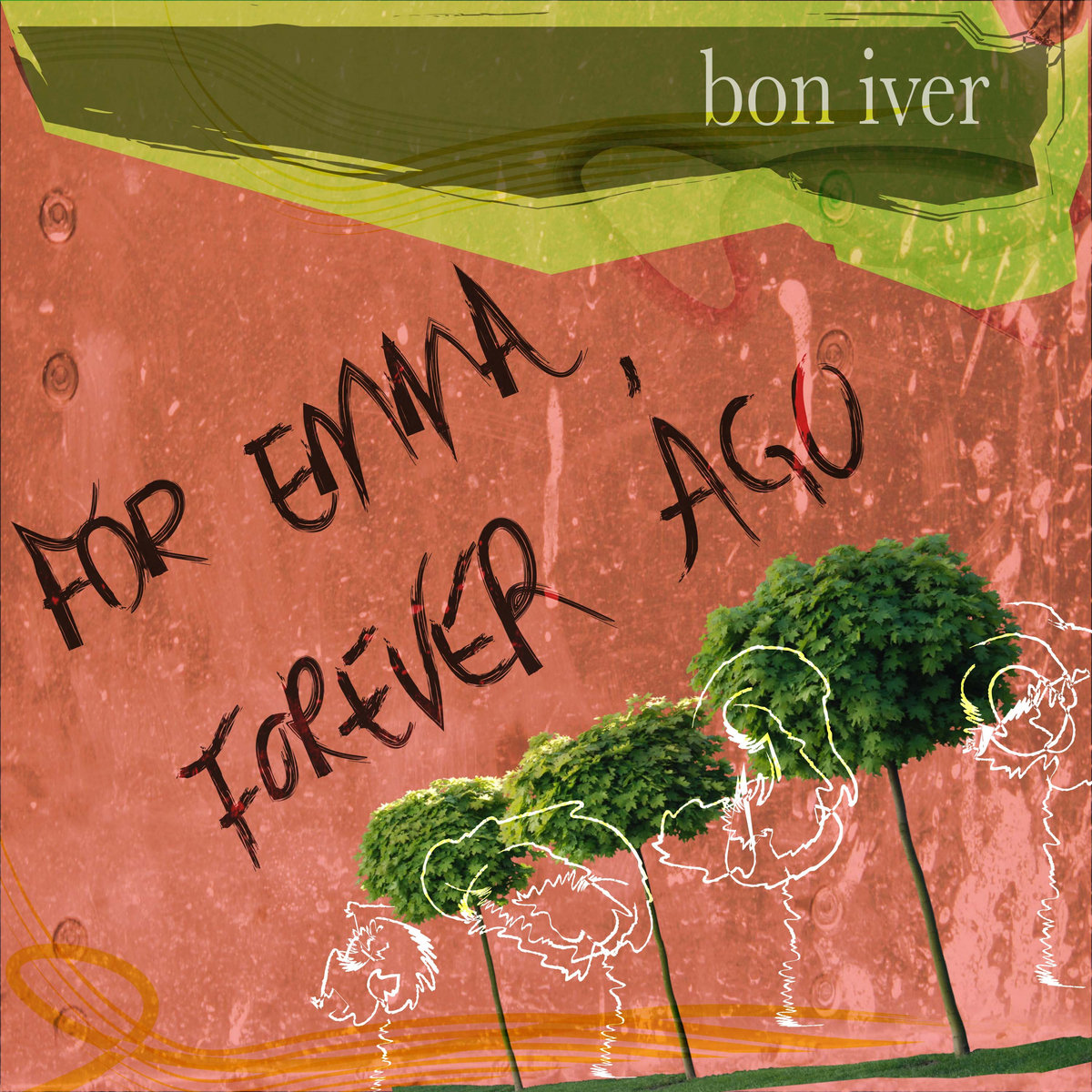

When he emerged, he had For Emma, Forever Ago, an album that didn’t just launch Bon Iver; it redefined what "indie folk" could sound like in the digital age.

There is a specific kind of magic in this record that people have been trying to replicate for nearly two decades. You’ve probably heard the imitators. You’ve heard the breathless acoustic guitars and the layered falsetto vocals in car commercials and indie movie trailers. But the original? It’s weirder than you remember. It’s rougher. It sounds like someone trying to find their way out of a dark room by feeling the walls.

The Cabin Is Real, But the Legend Is Complicated

People love a good hermit story. The narrative of the lone genius retreating from society to create a masterpiece is as old as time. With For Emma, Forever Ago, the myth-making started almost immediately after its self-release in 2007 and its subsequent 2008 wide release on Jagjaguwar.

The reality? Vernon wasn’t totally isolated. He was watching Northern Exposure DVDs. He was talking to his dad. But the emotional isolation was very real. That's the part people miss when they focus on the "cabin" aspect. It wasn’t about the wood siding or the lack of running water. It was about a total collapse of identity.

Most of the gear used was incredibly basic. We’re talking about an old Shure SM57 microphone and a Pro Tools rig that was probably crashing every twenty minutes. He used a Sears Silvertone guitar. Nothing fancy. Just grit and necessity. When you listen to the opening track, "Flume," you aren't hearing a studio-perfected folk song. You’re hearing a man layering his own voice until it sounds like a choir of ghosts. It’s haunting. It’s beautiful. It’s also deeply messy.

Breaking Down the Sound of Isolation

If you analyze the frequency response of the record, it’s muddy. And that’s why it works. Modern pop is obsessed with "high fidelity"—everything is crisp, separated, and shiny. For Emma, Forever Ago feels like it’s covered in a thin layer of dust.

Take "Lump Sum." The rhythmic clicking you hear in the background? That’s not a high-end percussion track. It’s just the sound of the room. It’s physical. You can practically feel the cold air leaking through the window frames. Vernon used a technique called "wordless vocalizing" a lot on this record. He wasn't always singing lyrics; he was singing shapes. He would record a vocal line, then record another one on top of it, reacting to the melody he’d just laid down.

👉 See also: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

The "Skinny Love" Phenomenon: This is the song everyone knows. It’s the one that got covered on The X Factor and The Voice a million times. But the original is aggressive. Vernon is slamming his guitar strings. He’s yelling. It’s a song about a relationship that is starving to death, and you can hear the desperation in his throat.

The Horns on "For Emma": Toward the end of the album, you start hearing brass. It feels like the sun finally coming out over the snow. It’s the moment where the internal monologue finally looks outward.

The Silence: There is so much space in this record. It’s not afraid to be quiet.

Why We’re Still Talking About This Album in 2026

It’s been a long time since 2007. Music technology has moved on. We have AI tools that can mimic Vernon’s falsetto in three seconds. We have plugins that "warm up" a digital track to make it sound like it was recorded in a cabin. So why does this specific 37-minute collection of songs still hold so much weight?

Authenticity is a buzzword that gets thrown around until it means nothing. But For Emma, Forever Ago represents a moment where a person was truly, terrifyingly honest with themselves. There was no "brand" to maintain. Vernon didn't think he was making a hit. He thought he was making a demo to show his friends.

That lack of self-consciousness is impossible to fake. You can tell when an artist is trying to "sound" like they’re in a cabin. They use too much reverb. They try too hard to be precious. This album isn't precious. It’s painful.

The Impact on the Indie Genre

Before this record, "indie folk" was often associated with the quirky, upbeat sounds of the mid-2000s—think banjos and handclaps. Bon Iver pushed it into a much darker, more experimental space. He proved that you could use folk instruments to create something that felt more like R&B or ambient music.

✨ Don't miss: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

Without this album, do we get the later, more experimental Bon Iver records like 22, A Million? Probably not. Do we get the massive success of artists like Phoebe Bridgers or even the "folklore" era of Taylor Swift? It’s hard to imagine that landscape without the blueprint Vernon laid down in Medford. He showed that intimacy could be a superpower.

Common Misconceptions About the Recording Process

A lot of people think Vernon went to the cabin specifically to record an album. He didn't. He went there to be alone. The recording happened almost by accident. He started messing around with the gear he had brought, and the songs just started to pour out.

- Myth: He played every single instrument perfectly.

- Fact: Much of the charm comes from the imperfections—the slightly out-of-tune guitar, the strained vocal takes.

- Myth: It was a high-tech "home studio."

- Fact: It was essentially a mobile rig in a basement.

The record wasn't even supposed to be called "Bon Iver." That name—a misspelling of the French "bon hiver" (good winter)—came later. It was a greeting from Northern Exposure, a show Vernon was watching to keep his sanity during those long Wisconsin nights. It’s a bit of trivia that makes the whole thing feel more human. He was just a guy watching TV and trying to stay warm.

The Technical "Magic" of the Falsetto

Let’s talk about the voice. Before this album, Justin Vernon was known as a baritone singer. He had a deep, soulful voice. But in the cabin, he started singing in a high, fragile falsetto. Why?

Part of it was the physical toll of his illness. Part of it was that he was trying to find a voice that didn't sound like his "old" self. The falsetto allowed him to detach. It allowed him to become a character in his own songs. When you hear the harmonies on "The Wolves (Act I and II)," it’s a wall of sound that feels like a physical weight. He wasn't just singing; he was building an environment.

He used the "Casiotone" keyboard sounds. He used whatever was lying around. This is the ultimate "limitation breeds creativity" case study. If he’d had a million-dollar studio and a team of producers, the album would have sucked. It would have been too clean. It would have lost the "air."

How to Listen to For Emma, Forever Ago Today

If you haven’t listened to it in a while, or if you’ve only heard the "Skinny Love" radio edit, you’re missing the point. This isn't background music for a coffee shop.

🔗 Read more: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

The best way to experience it is exactly how it was made: in isolation. Put on some headphones. Sit in a dark room. Let the hiss of the tape and the creak of the floorboards become part of the experience.

Key Tracks to Revisit

- Re: Stacks: This is the closing track. It’s just Vernon and an acoustic guitar. It’s the sound of someone finally letting go. "Everything that happens is from now on." It’s one of the most devastatingly hopeful lines in music history.

- Creature Fear: This track builds into a chaotic, noisy climax that most people forget is there. It shows that even at his most "folk," Vernon was always interested in noise and texture.

- Blindsided: The rhythm in this song is hypnotic. It feels like a heartbeat.

The Legacy of the Medford Winter

What Justin Vernon did in that cabin wasn't just record nine songs. He captured a feeling that everyone has felt at some point: the feeling of being completely lost and having to build yourself back up from nothing.

The album didn't just win awards or sell millions of copies. It gave people permission to be "messy" in their art. It proved that you don't need a massive budget or a major label to change the world. You just need a story, a microphone, and enough honesty to be uncomfortable.

Today, Vernon is a global superstar who collaborates with Kanye West and Taylor Swift. He plays arenas. But whenever he performs these songs, you can still see that guy in the cabin. The songs haven't aged a day because heartbreak doesn't age. Winter always comes back.

Your Next Steps with the Album

- Listen to the 10th Anniversary Live Version: Recorded at the Bradley Center, this version features a massive group of musicians (including members of the original DeYarmond Edison) and shows how these intimate songs can scale up to fill a stadium without losing their soul.

- Explore the "Jagjaguwar" catalog: If you like the raw, unpolished feel of For Emma, look into other artists on the label from that era, like Sharon Van Etten or Okkervil River.

- Try "The Land" Podcast: There are several deep-dive episodes from various music history podcasts that interview the people who were around Vernon at the time, providing a more grounded view of the "cabin" era.

- Check the Liner Notes: If you can get your hands on a physical copy, read the lyrics. They are often abstract and non-linear, reading more like poetry than standard verse-chorus-verse structures.

The most important thing you can do is give it your full attention. In an era of 15-second TikTok clips, a 37-minute album about a guy in the woods might seem like a slow burn. It is. But that’s exactly why it’s still necessary. Turn off your notifications, find a quiet spot, and let the snow fall.

The album isn't just a piece of music; it's a place you can go. And even twenty years later, the door to that cabin is still open.