You’re hunched over an engine block or maybe a high-end carbon fiber bike frame. The manual says 120. You look at your torque wrench. It’s scaled in foot-pounds. You think, "Eh, I’ll just crank it until it feels tight."

Stop.

That is exactly how bolts snap and threads strip. Honestly, the jump from foot pounds to inch pounds is the most common place where DIY mechanics and even some pro techs lose their minds. It's a simple math problem that carries massive mechanical consequences. If you mess up this conversion, you aren't just off by a little bit. You’re off by a factor of twelve. That’s the difference between a secure gasket and a cracked housing that costs three grand to replace.

The Math Behind Foot Pounds to Inch Pounds

Let’s get the math out of the way because it’s actually dead simple, even if it feels intimidating when you’re covered in grease. One foot is twelve inches. Physics doesn’t care about your feelings, so the relationship remains constant. To get from foot pounds to inch pounds, you multiply by 12.

If your spec sheet calls for 10 ft-lbs, you’re looking at 120 in-lbs. Easy.

But why do we even have two different scales? It’s about resolution and leverage. Think of it like measuring a diamond versus measuring a driveway. You wouldn't use a yardstick to weigh a wedding ring. Foot-pounds are for the big stuff—lug nuts, cylinder heads, suspension components. Inch-pounds are for the delicate stuff like transmission pan bolts, valve covers, and electronics housing.

When you use a big 1/2-inch drive torque wrench to hit a low inch-pound spec, you lose all "feel." Most torque wrenches are least accurate at the bottom 20% of their range. If you try to hit 120 in-lbs (10 ft-lbs) using a wrench that goes up to 250 ft-lbs, you’re basically guessing. You’ll likely blow right past the click before the tool even registers the movement.

Why Small Numbers Cause Big Headaches

I’ve seen it happen a hundred times. A guy is working on a valve cover. The manual says 85 inch-pounds. He grabs his big wrench, thinks "85 isn't much," and tries to find 7 foot-pounds on the dial. Most big wrenches don't even go that low. So he guesstimates. Snap. Now he’s drilling out a Grade 5 bolt from an aluminum head at 11:00 PM on a Sunday.

📖 Related: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

Mechanical engineers like Carroll Smith, who wrote the legendary Engineer to Win, obsessed over these details. The "clamp load" is what actually matters. When you turn a bolt, you’re essentially stretching a very stiff spring. The friction of the threads and the underside of the bolt head consume about 90% of the torque you apply. Only 10% actually goes into stretching the bolt to create the clamping force.

When you confuse foot pounds to inch units, you are either under-tightening (which leads to parts vibrating loose) or over-stretching the bolt past its yield point. Once a bolt reaches its yield point, it’s permanently deformed. It won’t hold tension anymore. It’s "meat-bolted," as some old-school guys say.

The Lever Arm Reality

Physics tells us that Torque = Force x Distance.

If you have a one-foot-long wrench and you put one pound of pressure on the end, that’s one foot-pound. If you have a one-inch-long wrench (imagine that tiny thing!) and put one pound of pressure on it, that’s one inch-pound.

This is why your tools are different sizes. Your 3/8-inch drive wrench is longer because it’s designed for the foot-pound range. Your 1/4-inch drive torque screwdriver or "inch-pounder" is short because you need more precision and less raw leverage. Using a long bar to hit an inch-pound spec is like trying to perform surgery with a machete. You have too much mechanical advantage, and you'll ruin the work before you even feel the resistance.

Real World Examples of the Foot Pounds to Inch Conversion

Let’s look at some common scenarios where this trips people up.

The Bicycle Carbon Fiber Nightmare

Modern mountain bikes and road bikes are miracles of engineering, but carbon fiber is brittle. Most stem bolts or seat post clamps require about 5 to 7 Newton-meters. In the US, that translates to roughly 44 to 62 inch-pounds. If you mistakenly try to apply 44 foot-pounds? You will hear a sickening crack that sounds like a gunshot. That’s your $3,000 frame becoming a very expensive wall ornament.

👉 See also: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

The Automotive Transmission Pan

Ever notice a slow drip after changing your transmission fluid? You probably over-torqued the bolts. Most pans require about 100 to 120 inch-pounds. People see "100" and their brain defaults to the more common foot-pound unit. They crank it down. The cork or rubber gasket gets crushed, squirts out the side, and the metal pan warps. Now it’ll never seal.

Small Engine Repair

Spark plugs in lawnmowers or chainsaws usually need about 15 foot-pounds. That’s 180 inch-pounds. If you use a big wrench, you risk stripping the threads in the soft aluminum cylinder head. If you use a tiny inch-pound wrench, you’ll feel exactly when that crush washer collapses and sets the seal.

Tools of the Trade: Don't Rely on Just One

You need at least two torque wrenches if you’re doing anything beyond changing a tire.

- A 1/2-inch Drive Wrench: Typically 30 to 250 ft-lbs. This is for lugs and axles.

- A 3/8-inch Drive Wrench: Usually 10 to 100 ft-lbs. This is your workhorse.

- A 1/4-inch Drive Wrench: Usually 20 to 200 in-lbs. This is for the "finesse" work.

Kinda expensive? Maybe. But cheaper than a tapped-out thread repair kit or a tow truck.

Also, remember that "click" type wrenches need to be stored at their lowest setting. If you leave your wrench dialed into 80 ft-lbs and throw it in the drawer for six months, the internal spring takes a "set." Next time you use it, 80 ft-lbs on the dial might actually be 95 ft-lbs in reality.

Newton-Meters: The Third Party

Just to make life harder, many modern manuals (especially for European cars like BMW or VW) use Newton-meters (Nm).

- 1 Foot-Pound = 1.356 Newton-Meters.

- 1 Inch-Pound = 0.113 Newton-Meters.

If you’re converting foot pounds to inch units, you’re staying within the Imperial system. But if you see "Nm" on a bolt head, don't guess. Use a conversion app. A lot of people think Nm and ft-lbs are "close enough." They aren't. 100 Nm is about 73 ft-lbs. If you tighten a 100 Nm bolt to 100 ft-lbs, you’ve over-torqued it by nearly 30%. That’s enough to cause a failure in high-stress applications like caliper brackets.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Talking About the Gun Switch 3D Print and Why It Matters Now

Common Misconceptions and Errors

People often think that more torque is always better. "Tight is tight, and too tight is broke," the saying goes. But "tight" is actually a specific engineering requirement.

Another mistake: using extensions. If you use a "crow's foot" adapter that extends the length of the wrench, the math changes. You’ve changed the "Distance" part of the Force x Distance equation. There are complex formulas for this, but the short version is: if the extension adds length to the wrench handle's axis, your torque reading will be lower than the actual torque applied to the bolt.

And for heaven's sake, don't use a torque wrench to loosen bolts. It’s a precision measuring instrument, not a breaker bar. Using it to crack a rusted bolt loose can knock the calibration out of alignment or even damage the ratcheting mechanism.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Project

Before you pick up a tool, do these three things:

Check the Units Twice

Look at the manual. Does it say ft-lb, in-lb, or Nm? If it says in-lb and your wrench is ft-lb, divide the number by 12 to see if your wrench can even handle it. If the result is in the bottom 10% of your wrench's range, go buy or borrow an inch-pound wrench.

Clean the Threads

Torque specs are usually "dry." If you put oil or anti-seize on the threads, you reduce friction. This means the same amount of torque will result in much higher clamp load. You could accidentally snap a bolt even while following the torque spec if the threads are lubricated when they’re supposed to be dry.

The "Two-Step" Method

Don't just go straight to the final number. If the spec is 120 in-lbs, tighten all the bolts in the sequence to 50 in-lbs first. Then go back and do the final pass at 120. This ensures the component seats evenly. This is vital for things like intake manifolds or cylinder heads where warping is a risk.

Quick Conversion Reference

- 5 ft-lbs = 60 in-lbs

- 10 ft-lbs = 120 in-lbs

- 15 ft-lbs = 180 in-lbs

- 20 ft-lbs = 240 in-lbs

- 25 ft-lbs = 300 in-lbs

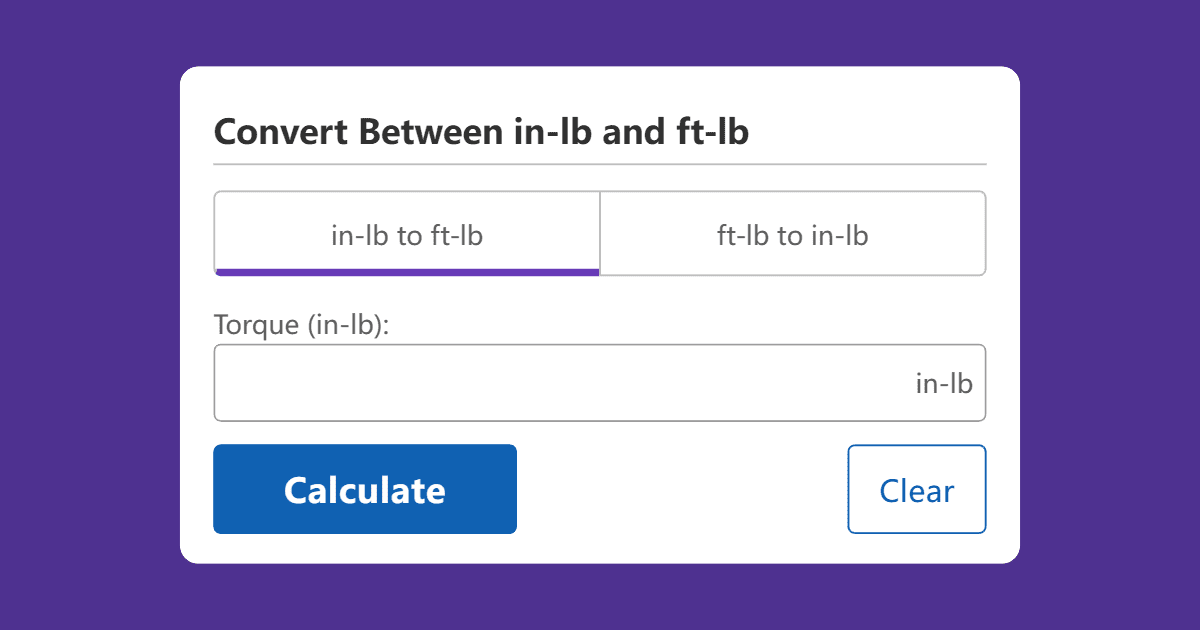

If you find yourself frequently converting foot pounds to inch pounds, write this 12-times table on a piece of masking tape and stick it to the inside of your toolbox lid.

Precision matters. A car is basically just a collection of vibrations held together by specific tensions. When those tensions are wrong, things fall apart. Literally. Take the extra thirty seconds to do the math, use the right scale, and keep your equipment calibrated. Your knuckles (and your wallet) will thank you.