Nature isn't a straight line. When you were in third grade, your teacher probably showed you a "food chain." It looked simple. A grasshopper eats grass, a frog eats the grasshopper, and a hawk eats the frog. It’s neat, tidy, and honestly, a bit of a lie. In the real world, that hawk isn't just waiting for a frog; it’s snagging a mouse, a snake, or maybe even a smaller bird. This chaotic, overlapping mess of "who eats whom" is exactly what we mean when we talk about a food web definition.

Think of it as the internet of the wilderness. Everything is plugged into everything else. If you pull one thread, the whole thing shudders. It’s a map of energy transfer, showing how the sun’s power moves from a blade of grass into the muscles of a mountain lion. But it's also a story of survival, competition, and the weird ways different species rely on each other to keep an ecosystem from collapsing into a heap.

The Gritty Reality of the Food Web Definition

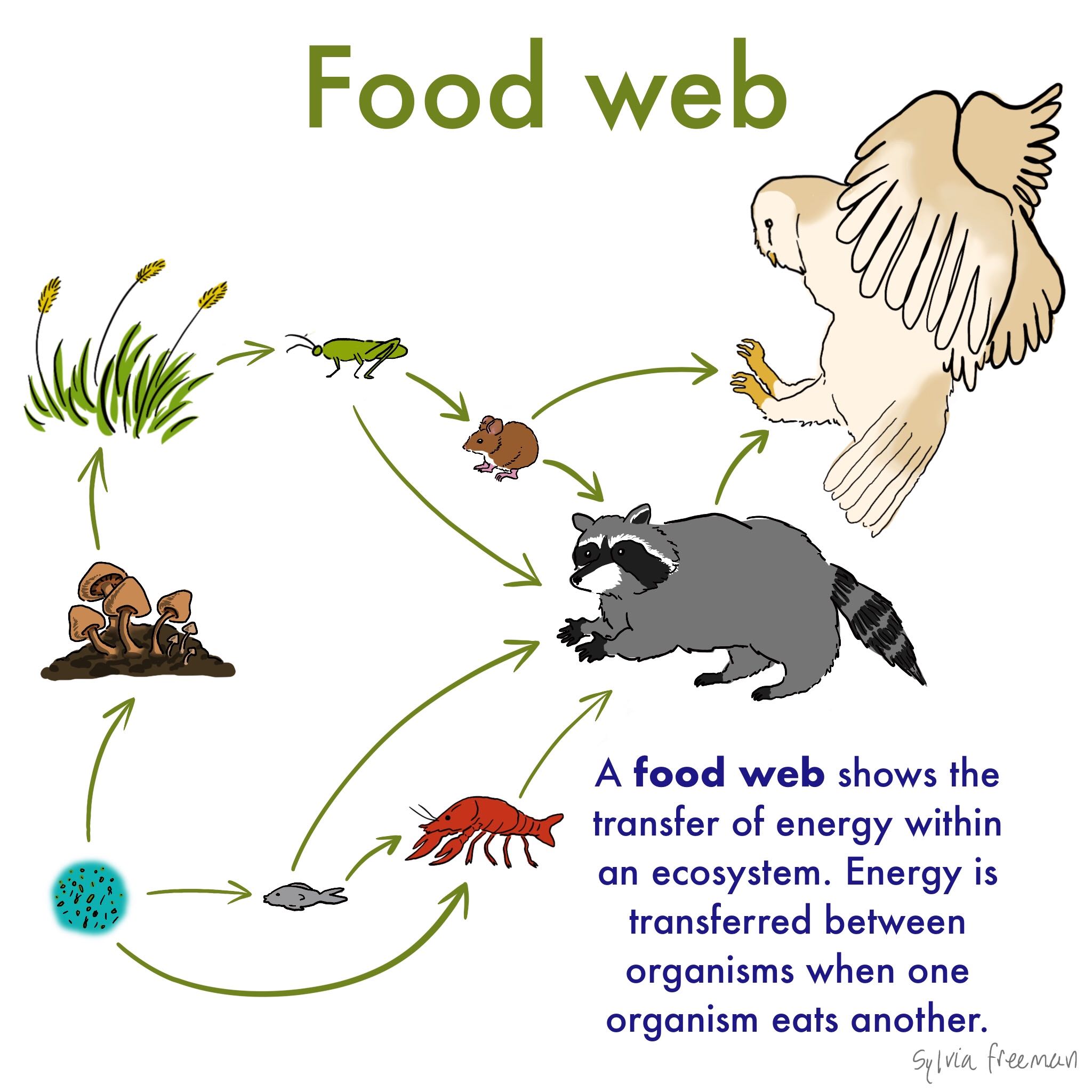

Basically, a food web is a collection of interconnected food chains. If a food chain is a single road, the food web is the entire highway system of Los Angeles. It’s complex. It’s messy. And it’s much more accurate for describing how life actually functions.

Most people get tripped up because they think of nature as a hierarchy—a ladder with humans or lions at the top. Biologists like Charles Elton, who really pioneered these ideas in the 1920s, realized it’s more of a circular, tangled knot. In his seminal work, Animal Ecology, Elton described "food cycles," which we now call webs. He noticed that most animals don't stick to one menu item. They are opportunists.

Take the grizzly bear in the Pacific Northwest. It’s the ultimate "it’s complicated" relationship. One day it’s eating spawning salmon. The next, it’s digging up moth larvae or grazing on huckleberries. The bear is a bridge between the aquatic food web and the terrestrial one. This is why the food web definition matters: it accounts for the fact that organisms often occupy multiple roles at once.

Producers, Consumers, and the "Bottom" of the Pile

You can't have a web without a starting point. Autotrophs, or producers, are the MVP here. These are your plants, algae, and some bacteria that pull energy out of thin air—well, out of sunlight via photosynthesis. Without them, the whole party stops.

Then come the heterotrophs. These are the "eaters."

- Primary consumers are the herbivores. Think deer, rabbits, or even tiny zooplankton in the ocean.

- Secondary consumers are the carnivores that eat the herbivores.

- Tertiary consumers are the big guys, the apex predators.

But wait. There’s a group that usually gets left off the fancy posters in classrooms: the decomposers and detritivores. Fungi, bacteria, and worms. They are the cleanup crew. Without them, the world would be piled high with dead stuff, and the producers would run out of nutrients. They turn the "web" into a "circle" by recycling nitrogen and carbon back into the soil.

Why Trophic Levels Are Kinda Fluid

Scientists use "trophic levels" to describe an organism's position in the web. It sounds fancy, but it just refers to the number of steps an organism is from the original energy source.

Level 1: Plants.

Level 2: Herbivores.

Level 3: Carnivores.

Here’s the catch: many animals are "trophic omnivores." They eat across different levels. A crow might eat a grain of corn (Level 2) and then turn around and eat a baby bird that just ate a worm (Level 4). This fluidity is why modeling a food web is a nightmare for researchers. You can't just put a bird in a box. It moves. It changes its diet based on the season.

Robert Paine, a famous ecologist, proved just how delicate these links are with his experiments on "keystone species." He found that if you remove a single predator—like a certain type of starfish in a tide pool—the entire food web falls apart. The mussels that the starfish used to eat suddenly take over, crowd out everything else, and the biodiversity of the area tanks. That's the power of the web. One missing link can trigger a "trophic cascade."

The 10% Rule and Why Big Predators Are Rare

Ever wonder why you see thousands of zebras but only a handful of lions? It’s basic math. Or, specifically, the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

Whenever energy moves from one level of the food web to the next, most of it is lost as heat. On average, only about 10% of the energy stored in one trophic level makes it to the next.

💡 You might also like: Why Ice Molds for Cocktails Are the Most Underrated Tool in Your Home Bar

If you have 1,000 calories of clover:

- The rabbits only get about 100 calories of that energy.

- The foxes that eat the rabbits only get 10 calories.

- The golden eagle that eats the fox gets 1 calorie.

This is why food webs rarely go beyond five or six levels. There just isn't enough energy left at the top to support a massive population of "super-predators." It’s also why being a vegetarian is more "energy efficient" for the planet, though most of us just like a good burger too much to care about the thermodynamics of our lunch.

Real-World Examples: From the Serengeti to Your Backyard

To really get the food web definition, you have to look at specific places. Let's talk about the Chesapeake Bay. It’s one of the most studied food webs on Earth.

At the base, you have phytoplankton. These tiny floating plants are eaten by bay anchovies and oysters. Those are then eaten by striped bass, which might eventually be eaten by an osprey or a human. But if too much fertilizer runs off from nearby farms, the phytoplankton grows out of control (an algal bloom). When it dies, bacteria eat it and use up all the oxygen. Suddenly, the fish die, the oysters suffocate, and the osprey has nothing to hunt. The web didn't just change; it broke.

In your own backyard, the web is just as active.

- The oak tree drops acorns.

- Squirrels eat the acorns.

- Hawks watch the squirrels.

- Meanwhile, a cat might be watching the hawk.

- And the ticks on the squirrel are sucking blood, acting as parasites (another weird branch of the food web).

Parasites are actually a massive, often ignored part of the food web definition. Some scientists argue that if you counted every "feeding link" in a forest, more of them would involve parasites than actual predators. It’s a bit gross, but it’s the truth.

Resilience and the "Redundancy" Factor

Nature is surprisingly smart. It builds in backups. In a healthy food web, there is "functional redundancy." This means multiple species do the same job.

If a forest has five different types of beetles that eat decaying wood, and a disease wipes out one species, the other four can pick up the slack. The web holds. But in ecosystems with low diversity—like a cornfield or a polluted pond—there’s no backup. If the one "primary consumer" disappears, the whole system collapses.

Climate change is currently testing this resilience. As oceans warm, some species of plankton are moving toward the poles. The fish that rely on them are left with an empty "pantry," and the birds that eat those fish are failing to raise their chicks. We're seeing the "re-wiring" of global food webs in real-time. It’s not always pretty.

How to Use This Knowledge

Understanding the food web definition isn't just for biology exams. It changes how you see the world.

If you’re a gardener, you realize that "pests" are just part of a web. Instead of spraying poison that kills everything (and starves the birds), you might plant flowers that attract predatory wasps to eat the aphids.

If you’re a consumer, you start to see why "apex predators" like tuna or swordfish carry more mercury. Because of "biomagnification," toxins build up as you go higher in the web. The little bit of mercury in a thousand tiny fish ends up concentrated in the one big fish at the top.

Practical Steps for Supporting Local Food Webs:

- Plant Native: Native plants support native insects, which are the "energy bridge" for birds and amphibians.

- Avoid Broad-Spectrum Pesticides: These are "web-killers." They don't just kill the bad guys; they starve the good guys.

- Leave the Leaves: Dead organic matter is the fuel for the decomposers that keep your soil alive.

- Support Biodiversity: Protect local wetlands and forests. The more complex a web is, the harder it is to break.

The next time you see a spider in its web, remember that you’re looking at a physical metaphor for the entire planet. We are all eating, being eaten, or waiting for something else to die so we can recycle the pieces. It’s not just "the circle of life"—it’s a massive, beautiful, terrifying web that keeps us all breathing. If you want to dive deeper, look into the work of Dr. Jane Lubchenco or the "World Food Web" models currently being used to track global sustainability. The more we map these links, the better chance we have of not accidentally cutting the ones we need to survive.