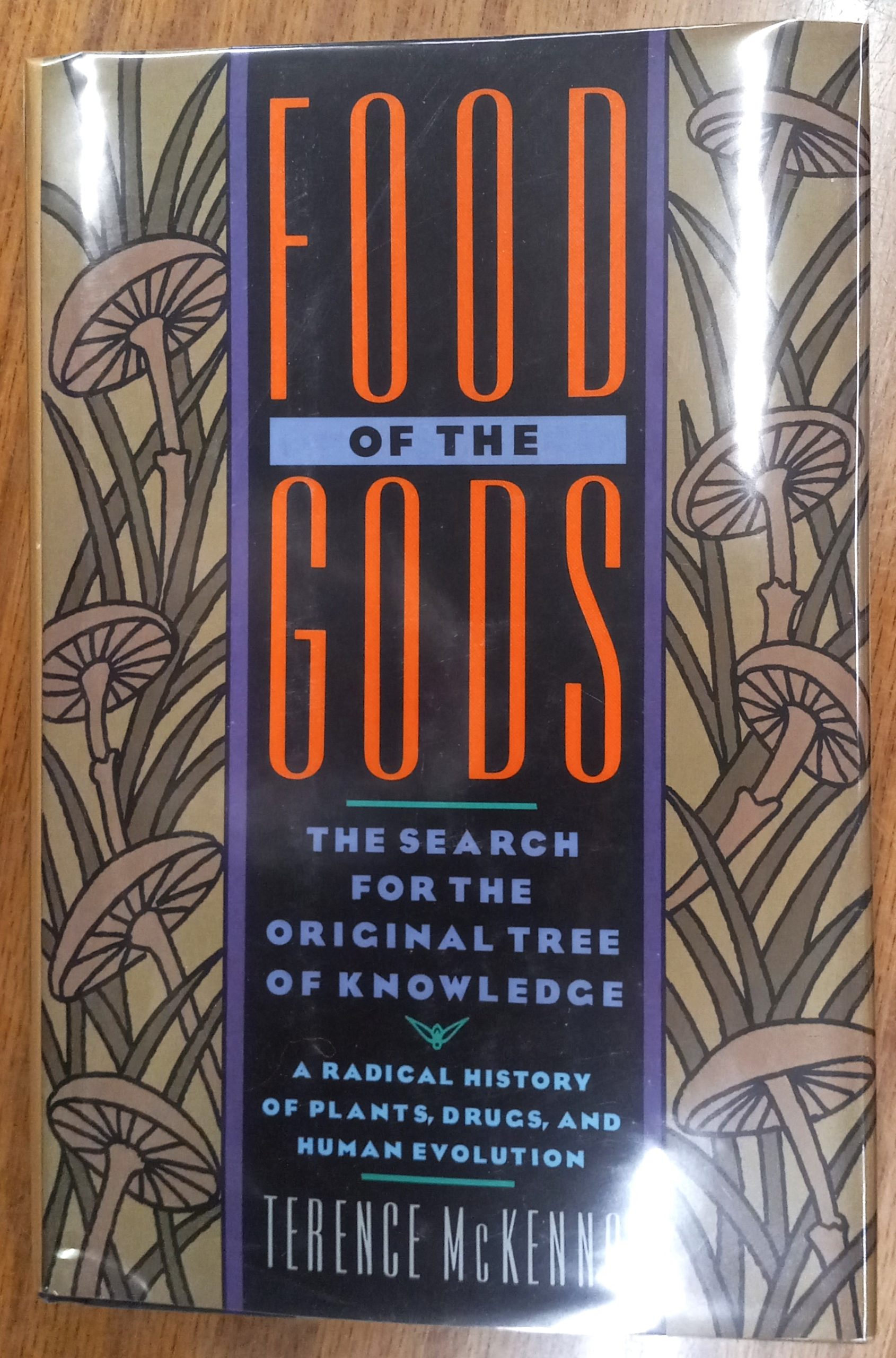

Terence McKenna was a man who lived in the cracks between worlds. He wasn't just an ethnobotanist; he was a silver-tongued bard of the bizarre. In 1992, he released Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge, a book that basically tried to rewrite the history of how humans became, well, human. It wasn't just a book about drugs. It was a manifesto.

He had this wild, raspy voice and a vocabulary that could make a dictionary feel insecure. McKenna argued that our rapid jump from "primitive" primates to self-aware, language-using humans wasn't just a random fluke of DNA. He thought we had help. Specifically, he pointed the finger at Psilocybe cubensis—magic mushrooms.

People called him crazy. They still do. But honestly, if you look at the current "psychedelic renaissance" happening in labs at Johns Hopkins or Imperial College London, McKenna starts to look less like a hippy with a telescope and more like a visionary who was just thirty years too early.

What is the Stoned Ape Theory?

The core of Food of the Gods Terence McKenna revolves around the "Stoned Ape Hypothesis." It’s a catchy name for a pretty complex idea. Imagine the North African jungles receding at the end of the last Ice Age. Our ancestors, these Homo erectus folks, are forced out of the trees and onto the grasslands. They’re hungry. They’re looking for anything to eat.

They start following herds of cattle. And where there is cattle dung in a humid environment, there are often mushrooms.

McKenna’s logic was based on three distinct levels of dosage. At very low doses, psilocybin actually increases visual acuity. If you’re a hunter on the savannah, seeing better means eating better. You survive; your kids survive. At slightly higher doses, it acts as an aphrodisiac and a "boundary dissolver," leading to more group bonding and, frankly, more babies.

But it’s the high doses—the "heroic doses," as he called them—that really matter.

He argued that these intense visions triggered the development of language. We needed a way to describe the impossible things we were seeing. Language is basically just symbolic representation. If you can see a spirit in a mushroom trance and try to tell your friend about it using sounds, you’ve just invented the precursor to every poem, technical manual, and tweet ever written.

Why Science Initially Laughed (And Why It's Listening Now)

For decades, mainstream biology treated McKenna like a radioactive uncle at a Thanksgiving dinner. They argued that there was no evidence. No fossil record of mushroom use. No way a "drug" could change the hardwiring of the brain over generations.

📖 Related: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

But then things got weird in the world of neuroscience.

We started learning about neuroplasticity. We found out that psilocybin doesn't just make you see "pretty colors." It physically rewires the brain. It dampens the Default Mode Network (DMN), which is the part of your brain responsible for your ego and your "autopilot" mode. When the DMN goes quiet, other parts of the brain that usually never talk to each other start a massive, cross-functional conversation.

It’s like the brain goes from a rigid bureaucracy to a free-flowing startup.

While modern scientists like Paul Stamets (the world-renowned mycologist) have championed a more refined version of this theory, they acknowledge McKenna started the fire. Stamets has noted that it’s not just about one mushroom. It’s about the entire fungal kingdom and its role in the ecosystem. McKenna's mistake might have been focusing only on psilocybin, but his intuition about the "external chemical catalyst" for human evolution is being taken seriously by people who aren't wearing tie-dye.

The Loss of the Goddess and the Rise of the Ego

One of the most poignant parts of Food of the Gods isn't the science; it's the social critique. McKenna wasn't just talking about the past. He was worried about the present. He believed that when we stopped using these "sacred plants," we lost our connection to the "Goddess"—the nurturing, interconnected spirit of the Earth.

He saw history as a 10,000-year-long "ego trip."

Basically, without the boundary-dissolving power of psychedelics, we became obsessed with hierarchy, property, and war. We traded the "partnership" model of society for the "dominator" model. He blamed alcohol and sugar for this, too. He called alcohol a "pro-ego" drug that encourages aggressive, linear thinking.

It's a heavy thought. You're sitting there reading about ancient primates, and suddenly you're questioning why our modern society is built on coffee-fueled productivity and beer-fueled relaxation instead of communal, visionary experiences.

👉 See also: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

Is It All Just a Fairy Tale?

Let’s be real for a second. There are massive holes in McKenna's narrative.

He was a master of "poetic truth." Sometimes he would gloss over contradictory archaeological evidence to make his story flow better. For instance, the timeline of the North African "green savannah" doesn't perfectly align with every stage of human brain expansion. Critics also point out that many cultures have used psychedelics for millennia without necessarily launching a technological revolution.

Also, he had a habit of being... well, very Terence. He talked about "Timewave Zero" and the end of the world in 2012. He was wrong about that.

But being wrong about the date of the apocalypse doesn't mean he was wrong about the fundamental relationship between humans and plants. You can't ignore the fact that almost every ancient civilization—from the Greeks with their Eleusinian Mysteries to the Aztecs and their "Flesh of the Gods"—had a cornerstone ritual involving an altered state of consciousness.

The Practical Legacy of Food of the Gods

So, what do we do with this information today? We aren't all going to go live in the rainforest and eat mushrooms (though some people try).

The legacy of Food of the Gods Terence McKenna is the realization that our current "normal" state of consciousness isn't the only one, or even necessarily the best one. It’s just the one that’s most useful for filing taxes and driving cars.

McKenna’s work has directly influenced:

- The decriminalization movements in cities like Denver, Seattle, and Detroit.

- The use of psilocybin in treating "end-of-life" anxiety for terminal patients.

- The concept of "microdosing" in Silicon Valley (even if he would have found the corporate aspect of it a bit soul-crushing).

He wanted us to have an "archaic revival." This doesn't mean going back to the Stone Age. It means reaching back into our history to find the tools we dropped along the way—tools that help us feel less alone and more connected to the planet.

✨ Don't miss: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you’re intrigued by McKenna’s world, don’t just take his word for it. He would have been the first person to tell you to go have your own experience. But since we live in a world of laws and science, here is how you can actually apply the "Food of the Gods" philosophy without losing your mind.

Start with Mycology, Not Just Psychedelics

Read Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake. It’s the modern, scientifically grounded sibling to McKenna’s work. Understanding how fungi connect the entire forest through the "Wood Wide Web" makes the idea of mushrooms influencing human evolution feel much more grounded in reality.

Audit Your "Legal" Drugs

McKenna was fascinated by how society chooses its poisons. Take a week to notice how caffeine, sugar, and alcohol affect your "vibe." Are they making you more "dominator-oriented"? Are they closing your boundaries or opening them? Just noticing is the first step toward the "archaic revival" he talked about.

Explore the "Flow State"

You don't need substances to experience boundary dissolution. Deep meditation, "breathwork," or even intense physical exercise can quiet the Default Mode Network. McKenna’s goal was the state, not necessarily the pill. Find what gets you out of your own head.

Respect the History

If you do choose to explore psychedelics, treat them with the weight McKenna gave them. They aren't "party drugs" in his worldview; they are teachers. Research the Indigenous cultures that have used these substances for thousands of years. Respect the lineage.

Terence McKenna died in 2000, but his ideas are more alive than ever. Whether the "Stoned Ape" is a literal biological fact or just a beautiful metaphor doesn't really matter as much as the question it asks: What are we missing by staying "sober" in a world that is clearly intoxicated with its own ego?

Next time you see a mushroom in the woods, maybe don't just walk past it. Think about the possibility that it, or something like it, might be the reason you’re able to think at all.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge

- Listen to the Archives: Search for the "McKenna OmniBus" or his lectures on YouTube. His voice is half the experience; his cadence and humor bring the text of Food of the Gods to life in a way reading can't quite match.

- Compare the Theories: Look up the "Social Brain Hypothesis" by Robin Dunbar. It’s the mainstream scientific alternative to McKenna’s theory, focusing on social grooming and group size rather than diet. Seeing where they overlap and where they clash is where the real learning happens.

- Support Research: Follow organizations like MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies). They are doing the hard, clinical work to prove—or disprove—the therapeutic claims McKenna made decades ago.

The "Food of the Gods" isn't just a historical curiosity. It's a lens through which we can view our own potential. Even if McKenna was only 10% right, that 10% changes everything we think we know about being human.