When you search for foetal alcohol syndrome photos, you're usually looking for a specific set of facial markers. It’s human nature. We want a visual shortcut to understand a complex medical reality. But here’s the thing—the "classic" face of Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) is actually becoming less central to how doctors talk about the condition today.

Basically, the face is just the tip of the iceberg.

It's heavy. It's controversial. And honestly, it's often misunderstood. For decades, medical textbooks relied on a very specific set of images to teach students what to look for: the thin upper lip, the smooth philtrum (that little groove between your nose and mouth), and the small eye openings. But if you only look at the photos, you miss the 90% of the condition that happens inside the brain. We’re moving toward a broader umbrella called Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD), where the physical "look" might not be present at all, even if the neurological impact is profound.

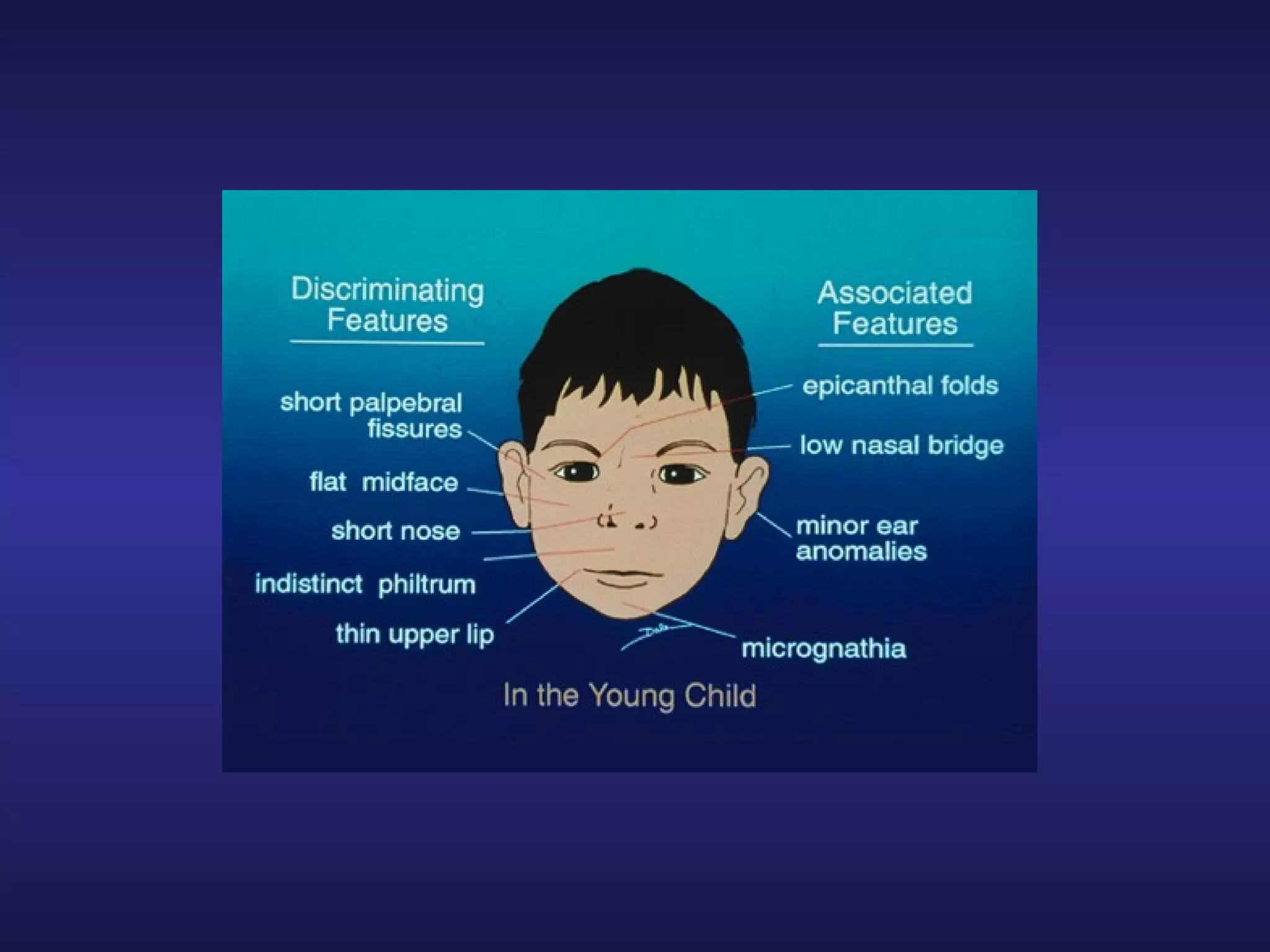

The specific facial markers in foetal alcohol syndrome photos

If you look at clinical photos used by organizations like the CDC or the American Academy of Pediatrics, you’ll notice three distinct "sentinel" features. These aren't just random observations. They are measured using very specific tools, like the Lip-Philtrum Guide developed by Dr. Susan Astley at the University of Washington.

First, there’s the palpebral fissure length. That’s just a fancy way of saying the horizontal length of the eye opening. In many foetal alcohol syndrome photos, these openings are noticeably short. It’s not about the shape of the eye itself, but the width of the "slit."

Then you have the smooth philtrum. In most people, there are two distinct ridges running from the nose to the lip. In a child with full FAS, this area is often completely flat. Doctors actually use a 5-point scale to rank this. A "1" is a deep groove, while a "5" is totally smooth.

The third major marker is a thin upper lip. We aren't talking about "naturally thin" lips that run in a family. We’re talking about an upper vermilion border that is barely visible. When these three things appear together, it’s a high-confidence indicator that alcohol exposure occurred during a very specific window of embryonic development—usually around the 19th or 20th day of pregnancy when the midline of the face is forming.

It’s precise. It’s fleeting. And if the exposure happened a week later? The face might look totally "normal," but the brain could still be significantly affected.

🔗 Read more: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

Why the photos don't tell the whole story

Focusing strictly on foetal alcohol syndrome photos can actually be kinda dangerous. Why? Because it leads to a "missing" population.

Most people on the spectrum (FASD) do not have the facial features. In fact, research suggests that as many as 80% to 90% of individuals with brain damage from prenatal alcohol exposure don't have the "classic" look. They have what used to be called Neurodevelopmental Disorder-Alcohol Exposed (ND-AE).

Think about that.

If a teacher or a doctor is only looking for the face they saw in a textbook, they’re going to miss the kid who is struggling with executive function, memory, and impulse control. They’ll just see a "naughty" kid or a child with "unexplained" ADHD. The photos provide a visual "smoking gun," but the absence of those features doesn't mean the person is fine.

Dr. Kenneth Lyons Jones, one of the original pediatricians who identified FAS in 1973, has spent years emphasizing that the brain is far more sensitive to alcohol than the face is. The facial features only form if alcohol is present in the system during a very narrow window of the first trimester. Alcohol exposure in the second or third trimester impacts the wiring of the brain—the corpus callosum, the cerebellum, the basal ganglia—but it won't change the shape of the lip or the eyes.

The "invisible" disability and the stigma of the image

There is a massive stigma attached to these photos. When parents—especially adoptive or foster parents—see foetal alcohol syndrome photos, they often feel a sense of dread. They worry about the future. They worry about what society will see.

But here is a reality check: facial features often fade.

💡 You might also like: Blackhead Removal Tools: What You’re Probably Doing Wrong and How to Fix It

As children grow into adolescence and adulthood, the philtrum can become more defined. The face grows. The "look" becomes less obvious. This is why adult diagnosis is so incredibly difficult. If you don't have childhood photos or a clear maternal history, a doctor might have no physical evidence to go on.

We also have to talk about the "look" across different ethnicities. For a long time, the diagnostic charts were based primarily on Caucasian children. This led to massive underdiagnosis (and sometimes overdiagnosis) in other populations. Expert teams now use different "norms" for different racial backgrounds to ensure they aren't misreading a child's natural heritage as a medical symptom.

What's actually happening in the brain?

If you could take "photos" of the brain—and we can, with MRIs—you’d see a much more startling picture than what you see on the surface.

In some cases of heavy exposure, the corpus callosum, which is the bridge of fibers connecting the left and right hemispheres of the brain, is thin or even completely missing. This is why a person with FASD might "know" a rule (left brain) but can't "apply" it in the heat of the moment (right brain). The connection is literally frayed.

The cerebellum is another area often visible in neuro-imaging. It’s responsible for motor control, but also "timing" in social interactions. This is why kids with FASD often struggle with personal space or "getting" a joke at the same time as everyone else. It’s not a behavior problem. It’s a hardware problem.

The diagnostic shift: Beyond the snapshot

In 2026, the medical community is moving toward a more holistic diagnostic process. We don't just look at a photo and say "Yes" or "No."

The current gold standard involves a multi-disciplinary team:

📖 Related: 2025 Radioactive Shrimp Recall: What Really Happened With Your Frozen Seafood

- A pediatrician to check growth and physical markers.

- A psychologist to test IQ and executive function.

- A speech-language pathologist to look at communication nuances.

- An occupational therapist to check sensory processing.

They look at 10 different brain domains. If a person shows significant impairment in three or more of these domains—and there is confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure—they get the diagnosis, regardless of what their upper lip looks like.

Honestly, this shift is saving lives. It’s moving the conversation away from "How does this child look?" to "How does this child learn?"

Actionable steps for parents and caregivers

If you are looking at foetal alcohol syndrome photos because you're concerned about a child in your care, the photo is not your answer. It's just a starting point.

- Document everything. If you are an adoptive parent, try to find any photos of the child from infancy or early toddlerhood. These are often more "telling" than current photos because facial features change with puberty.

- Seek a FASD-informed clinic. A regular pediatrician might not have the specific training to measure a philtrum correctly or understand the nuances of the spectrum. You need a specialist.

- Focus on "Brain-Based" parenting. If a diagnosis is suspected, stop punishing the "behaviors." If the brain can't process the "why," the punishment won't work. Look into the "Neurobehavioral Model" pioneered by experts like Diane Malbin. It’s a game-changer.

- Ignore the "Normal" milestones. Kids on the spectrum often have a "developmental age" that is about half their chronological age in terms of social and emotional maturity. Adjust your expectations accordingly.

- Get a baseline MRI if possible. While not always necessary for diagnosis, having a clear picture of the brain's structure can help tailor educational support (IEPs) in school.

The most important thing to remember is that a photo is a static image of a single moment. A child with FASD is a dynamic, growing human being with strengths that a camera can't capture. They might be incredibly artistic, deeply empathetic, or technically gifted. The physical markers are just clues for doctors to unlock the right support systems.

Don't let the "look" define the potential. Diagnosis isn't a dead end—it's the map that tells you which road to take so the child can actually succeed.

Next Steps for Implementation

- Consult the FASD United (formerly NOFAS) directory to find a diagnostic clinic in your state that specializes in the 4-Digit Diagnostic Code.

- Request a "Functional Assessment" from your school district rather than just a standard IQ test; this measures real-world adaptive skills which are often lower than IQ in individuals with FASD.

- Review the University of Washington's Lip-Philtrum Guides if you are a medical professional to ensure you are using the correct age-adjusted and race-adjusted charts for physical screenings.