You're staring at a 2x2 contingency table. Maybe you're looking at a small clinical trial or a niche A/B test for a specialized software feature. You have a handful of successes and a handful of failures. Naturally, your brain screams "Chi-square!" because that’s what we’re taught in Stats 101. But then you notice something unsettling. One of your cells has a count of 3. Another has a zero. This is exactly when things get messy, and it's where the Chi-square test starts to fall apart. Honestly, if you try to force a Chi-square on tiny datasets, you're basically guessing. That’s why you need to know exactly when to use Fisher's exact test before you report a p-value that doesn't actually exist.

The Small Sample Crisis

Small data is a nightmare for standard frequentist statistics. Most tests we use—like the Chi-square or the G-test—are "asymptotic." This is a fancy way of saying they assume your data follows a smooth, predictable curve (like the normal distribution) as your sample size grows toward infinity. But your data isn't infinite. It’s 12 people in a room.

📖 Related: Tell Me a Joke: Why Humor is the Next Frontier for Silicon Valley and Our Sanity

When your sample size is tiny, that smooth curve looks more like a jagged mountain range. The Chi-square test relies on an approximation that breaks down when "expected" cell frequencies drop below 5. This isn't just a suggestion; it's a mathematical cliff. If you ignore it, your p-value becomes a work of fiction.

Fisher's exact test is the solution because it doesn't approximate anything. It calculates the exact probability of seeing your specific data—and every configuration more extreme than yours—under the null hypothesis. It’s computationally heavy, sure, but in the era of modern computing, that doesn't matter for the small-scale tables where it's most needed.

The Core Mechanics: Hypergeometric Distribution

Ronald Fisher—the guy who literally wrote the book on modern statistics—developed this test while trying to solve "The Lady Tasting Tea" problem. A colleague, Muriel Bristol, claimed she could tell if the milk or the tea was poured into the cup first. Fisher didn't want an approximation. He wanted to know the exact odds she was just lucky.

The math behind this is the hypergeometric distribution. Unlike the Chi-square, which looks at the squared differences between observed and expected counts, Fisher’s looks at the permutations of the data.

$$P = \frac{\binom{a+b}{a} \binom{c+d}{c}}{\binom{n}{a+c}} = \frac{(a+b)! (c+d)! (a+c)! (b+d)!}{n! a! b! c! d!}$$

👉 See also: Why the Broken Script Has Failed to Load Correctly (and How to Kill the Error for Good)

Don't let the factorials scare you. Basically, the test assumes the "marginals" (the row and column totals) are fixed. If you have 10 people treated and 10 in a control group, and 5 people total got better, the test asks: "Of all the ways I could distribute those 5 'successes' among 20 people, how many ways would result in a split this lopsided or worse?"

When to Use Fisher's Exact Test: The Rule of Five

If you're looking for a hard and fast rule, here it is: Use Fisher’s when more than 20% of your expected cell counts are less than 5.

Many people think this rule applies to the observed counts (the numbers you actually see in your table). It doesn't. It applies to the expected counts—what you’d expect to see if there was no relationship between the variables. If any single expected cell count is less than 5, the Chi-square p-value is officially suspect.

Actually, many modern statisticians argue you should use Fisher’s for all 2x2 tables if your software can handle it. Why approximate when you can be exact?

The Medical Research Reality

In rare disease research or Phase I clinical trials, you rarely have the luxury of 500 participants. You might be comparing a new gene therapy against a placebo in a group of 15 patients.

Let's say 4 out of 7 treated patients recovered, while 0 out of 8 placebo patients did.

- Chi-square might give you a p-value of 0.03.

- Fisher’s Exact Test might give you 0.07.

See the danger? One tells you it's statistically significant; the other tells you it might just be a fluke. In medicine, that distinction is the difference between a breakthrough and a dangerous mistake. Fisher's is the "conservative" choice here, but conservative in statistics usually means "not being wrong."

💡 You might also like: Why The Inmates Are Running the Asylum Book Still Explains Your Worst Tech Nightmares

Limitations and the "Fixed Marginals" Debate

Nothing is perfect. The biggest criticism of Fisher's exact test is that it’s "too conservative." Because it assumes the row and column totals are fixed, the p-values can be slightly higher than they "should" be, leading to a higher Type II error rate (missing a real effect).

In some experiments, the marginals aren't actually fixed. If you're conducting a survey and just happens to get 40 men and 60 women, those totals were random. Fisher’s assumes you intended to have exactly 40 men and 60 women. This is a bit of a statistical "inside baseball" debate, but it’s worth noting that for very specific experimental designs, the Barnard’s test might actually be more powerful. But honestly, for 99% of researchers, Fisher's is the gold standard for small samples.

Beyond the 2x2 Table

You can technically use Fisher’s for larger tables—like a 3x3 or a 2x4. This is often called the Fisher-Freeman-Halton extension.

However, be warned: the computational complexity explodes. If you have a 5x5 table with large-ish numbers, your computer might start humming and then give up. For anything larger than 2x2 where you still have small cell counts, you'll likely need to use a "Monte Carlo" simulation of Fisher's test. This provides an estimate of the exact p-value by randomly shuffling the data thousands of times rather than trying to calculate every single possible permutation.

Practical Steps for Your Analysis

If you're sitting with data right now, follow this workflow.

First, check your total sample size (N). If N is over 1000 and all your cells have big numbers, just use Chi-square. It’s faster and perfectly accurate at that scale.

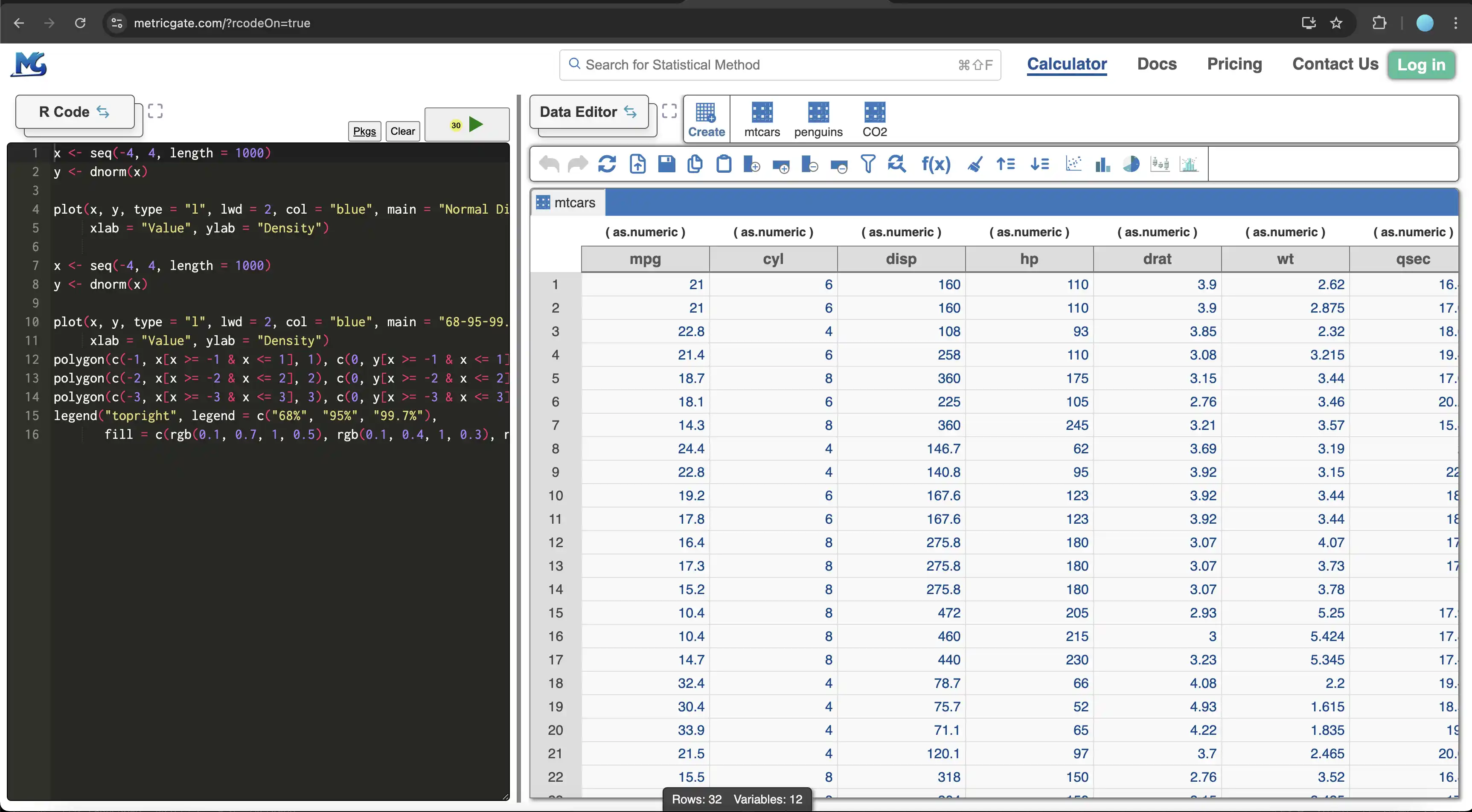

Second, look at your expected frequencies. If you’re using R, you can check this with chisq.test(table)$expected. If any number in that output is less than 5, stop what you're doing. Switch to fisher.test(table).

Third, decide if you need a one-tailed or two-tailed test. Most of the time, you want two-tailed. You’re looking for any difference, not just a difference in one specific direction.

Lastly, look at the Odds Ratio. Fisher's test in most software packages (like R or Python’s SciPy) will provide an estimate for the Odds Ratio along with a confidence interval. This gives you the "effect size," telling you not just if there's a relationship, but how strong that relationship is.

Why It Matters for SEO and Digital Marketing

Even if you aren't a scientist, you've probably encountered this in A/B testing. Marketers love to declare a "winner" after three days of testing a new landing page. If your "Buy Now" button has 2 conversions out of 40 clicks on Version A and 0 conversions out of 38 clicks on Version B, a standard A/B testing calculator might give you a "confidence level" that is totally misleading.

Running a Fisher's Exact Test on those numbers would likely show a p-value well above 0.05, signaling that you need more data before making a business decision. It prevents you from chasing ghosts in your data.

Immediate Next Steps for Implementation

- Audit your current tools: Check if your A/B testing software or statistical package defaults to Chi-square. If it doesn't automatically switch to Fisher's for small samples, you need to calculate it manually.

- Run a sensitivity check: If you have a "borderline" significant result ($p \approx 0.045$) with a Chi-square on a medium-sized sample, run Fisher's test as a sanity check. If the Fisher p-value jumps to 0.06, your result isn't as robust as you think.

- Verify your assumptions: Ensure your observations are independent. Fisher’s test, like the Chi-square, assumes that one person's outcome doesn't affect another's. If you have repeated measures from the same person, you need McNemar's test instead.

- Report the Odds Ratio: Don't just report the p-value. Use the Fisher's output to provide the 95% confidence interval for the Odds Ratio, which gives your audience a much clearer picture of the actual impact.