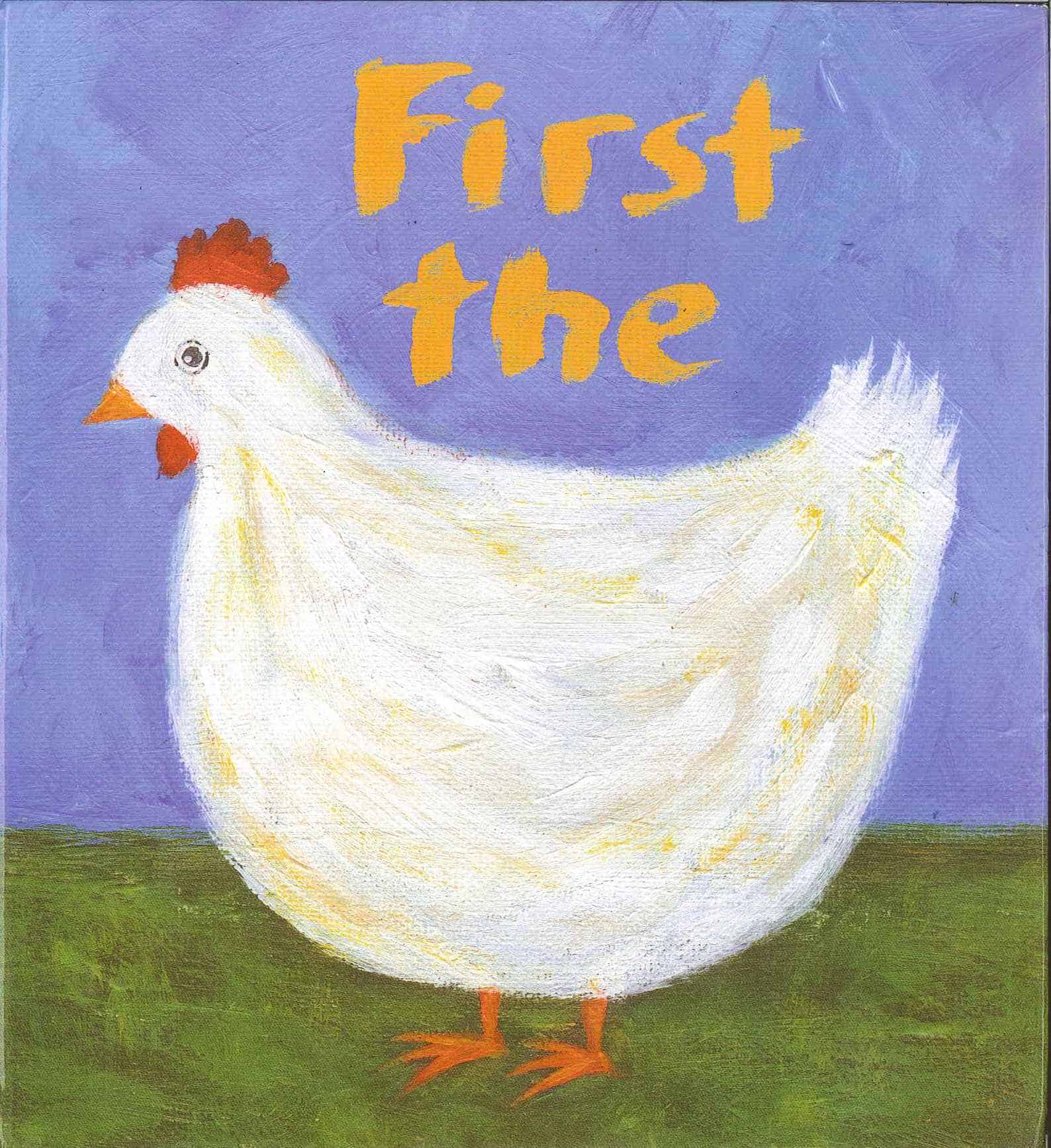

It looks like a simple board book. You see the die-cut circle on the cover, a splash of yellow, and a title that hints at the world’s oldest philosophical debate. But First the Egg by Laura Vaccaro Seeger isn't just another nursery shelf-filler meant to distract a toddler for five minutes while you try to drink a lukewarm coffee. It’s actually a masterclass in minimalism.

Honestly, it’s rare to find a book that says so much by saying almost nothing at all.

When it first hit shelves in 2007, it didn't just lean on cute illustrations. It used physical space. It used the literal paper to tell a story about transformation. Published by Roaring Brook Press, the book quickly became a staple in early childhood education, eventually earning a Caldecott Honor and a Theodor Seuss Geisel Honor. That’s a massive deal. Most books are lucky to get a nod from one committee; Seeger managed to impress the folks looking at art and the ones looking at literacy simultaneously.

What First the Egg Actually Teaches (It’s Not Just Biology)

If you’ve never held it, the hook is the die-cut. You see an egg. You flip the page, and that same shape—through a clever cutout—becomes the body of a chick. It’s "First the egg, then the chicken." Simple, right? But then Seeger pivots. "First the tadpole, then the frog." "First the seed, then the flower."

It’s about the "then."

We spend so much time focusing on the finished product—the flower in the garden or the butterfly in the air—that we forget the messy, quiet, stationary beginning. For a three-year-old, this is a lesson in patience and time. For the adult reading it for the fiftieth time that week, it’s a weirdly profound reminder that everything starts as something else. Growth isn't an explosion; it's a sequence.

The paint texture is something else too. Seeger doesn't use flat, digital colors. She uses thick, impasto-style strokes. You can almost feel the ridges of the paint on the page. This tactile quality is why the book thrives in a physical format. You can’t replicate the "First the Egg" experience on an iPad. The screen lacks the soul of the heavy paper and the physical reveal of the cutout.

The Wordless Shift

Then, the book does something brave. It stops using words.

Towards the end, we see "First the word, then the story." We see "First the color, then the painting." It moves from biological metamorphosis to creative metamorphosis. This is where Seeger shows her hand as an artist. She’s telling the reader—and the child—that they have the power to turn raw materials into something complex.

A single "word" on a page leads to a chaotic, beautiful spread of a storybook. A few "colors" lead to a vibrant landscape. It’s a meta-commentary on the very book you’re holding. It’s basically telling the kid, "Hey, I started with an egg of an idea, and now you’re holding the chicken."

Why the Caldecott Committee Cared

The Caldecott Medal is usually about the "most distinguished American picture book for children." Usually, people think that means the most detailed or the most ornate. But in 2008, the committee recognized First the Egg because of how the design is the narrative.

🔗 Read more: Big Tits in the UK: Why Average Bra Sizes Are Actually Skyrocketing

The negative space is intentional.

Look at the "First the caterpillar, then the butterfly" spread. The caterpillar is small, almost lonely on the page. When you turn that page, the wings of the butterfly explode across the gutter. It’s a rhythmic use of scale. Critics like those at The Horn Book and School Library Journal pointed out that Seeger’s ability to manage "the reveal" is what sets her apart from other concept book authors.

There’s a tension in every page turn. Even if a child knows what comes next, the physical act of flipping the page to see the transformation through the die-cut hole creates a hit of dopamine. It’s interactive without needing batteries or a Wi-Fi connection.

The Controversy of the "Chicken or the Egg"

You can’t write a book titled First the Egg without poking the bear of the ancient paradox. Who came first?

Seeger handles this with a wink. The book ends by circling back. It doesn't provide a scientific dissertation on evolutionary biology or the genetic mutations that led from a proto-chicken to the first true Gallus gallus domesticus egg. Instead, it creates a loop.

The ending suggests that "first" is a matter of perspective. It’s a circle.

Some parents find this frustrating. They want a definitive answer to give their kid. But most educators love it because it sparks a conversation. It’s an "open" text. It allows the child to ask, "But where did that egg come from?" And suddenly, you’re talking about the cycle of life at 7:00 PM on a Tuesday while you’re trying to get them to brush their teeth.

Comparing Seeger to Her Peers

If you look at Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar, the focus is on consumption and the days of the week. It’s a linear progression. Seeger’s work feels more like Lois Ehlert’s Color Zoo but with more emotional weight. While Ehlert focused on geometric shapes, Seeger focuses on the essence of change.

There’s also a certain "quietness" here that you don't find in the loud, neon-colored books that dominate Amazon’s best-seller lists today. First the Egg doesn't scream. It whispers.

Technical Mastery in the Artwork

Let’s talk about the medium. Seeger uses acrylics on canvas.

The choice of canvas is vital. If she had used watercolor, the book would feel light and airy. By using thick acrylics, the objects—the egg, the seed, the tadpole—feel heavy and real. They have gravity. When the "seed" becomes the "flower," the flower looks like it has been carved out of the page.

The color palette is also surprisingly sophisticated. We aren't just looking at primary red, yellow, and blue. We’re looking at ochres, deep forest greens, and variegated browns. It respects the child’s eye. It assumes the child can appreciate nuance in tone.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Pic of Mullet Haircut for Your Face Shape

The Psychology of the Die-Cut

There’s actual developmental psychology at play here.

Toddlers are obsessed with object permanence. They are also obsessed with "hiding" and "finding." The die-cut hole acts as a peek-a-boo mechanism. It allows the child to see a piece of the future while they are still in the present. This bridges the cognitive gap between "what is" and "what will be."

It’s a visual representation of potential.

Real-World Impact and Longevity

Since 2007, the book has been translated into multiple languages and has become a staple in "Storytime" sets at public libraries. Why? Because it works for a group. You can hold it up in a room of twenty screaming toddlers, and the "reveal" of the chick through the hole will almost always get a collective "Ooh."

It’s also a favorite for "Concept" units in preschools.

Teachers use it to bridge the gap between art and science. One day you’re talking about how frogs grow, and the next you’re talking about how to mix yellow and blue to get the green on the frog's back. It’s a multi-tool.

Is it still relevant in 2026?

With the rise of "AI-generated" children's stories—which are often visually cluttered and narratively hollow—a book like First the Egg stands out even more. It is human-centric. You can see the hand of the artist in every brushstroke. In a world of digital perfection, the "imperfections" of Seeger’s canvas and the physical tactile nature of the cutouts feel like a relief.

It reminds us that the best way to teach a child isn't through a screen, but through something they can touch, turn, and ponder.

Common Misconceptions About the Book

People often think this is a "baby book."

Sure, the word count is low. But the concepts—especially the shift from biology to art—are actually quite advanced. I’ve seen middle school art teachers use this book to explain the concept of "minimalism" and "composition."

Another misconception is that it’s purely a science book. It isn't. If you want a book about the life cycle of a chicken, go find a non-fiction title with photos. This is a book about transformation. It’s about the poetry of becoming.

Actionable Ways to Use First the Egg

If you’re a parent, educator, or just a fan of good design, don't just read the book once and put it away.

💡 You might also like: The Claw Foot Tub Bathroom: What Most People Get Wrong About This Classic Choice

- The "Trace and Guess" Game: Before flipping the page, have the child trace the shape of the die-cut with their finger. Ask them what else that shape could become. A circle isn't just an egg; it could be a sun, a wheel, or a cookie.

- Texture Exploration: Use the book as a prompt for a "thick paint" art project. Give the kids palette knives or just pieces of cardboard and let them smear acrylic paint to see if they can recreate the "ridges" Seeger uses.

- The Reverse Narrative: Ask the child to tell the story backward. "Before the chicken, there was the..." This helps with sequencing and understanding causality.

- Find the "Egg" in Your House: Look for things that are "beginning" stages. A pile of flour (before the cake), a ball of yarn (before the sweater), or a blank piece of paper (before the drawing).

The real magic of First the Egg isn't in the answer to the riddle. It’s in the realization that everything, including the child reading the book, is in a constant state of becoming something bigger. It’s a quiet, beautiful, and essential addition to any library. Just make sure you get the hardcover or the high-quality board book version; the experience is entirely in the paper.