You’re out there. Somewhere between the red rocks of Moab and the high desert of Nevada, the bars on your phone just... vanish. It happens fast. One minute you're streaming a podcast, and the next, your GPS is spinning a circle of death while you stare at a dusty fork in the road. This is exactly why a physical or high-quality digital western US map with roads isn't just a nostalgia trip for people who miss the 90s. It is a survival tool.

The West is huge. Like, mind-bogglingly empty. You can drive for three hours in Wyoming and see more pronghorn than people. When you’re looking at a western US map with roads, you aren't just looking at lines on paper; you're looking at a gateway to the last truly wild places in the lower 48. But here’s the thing: not all maps are created equal. Most people grab a gas station fold-out and think they're set, but they’re usually missing the nuance of BLM land, forest service routes, and those seasonal passes that stay snowed in until July.

The Reality of Mapping the Great American West

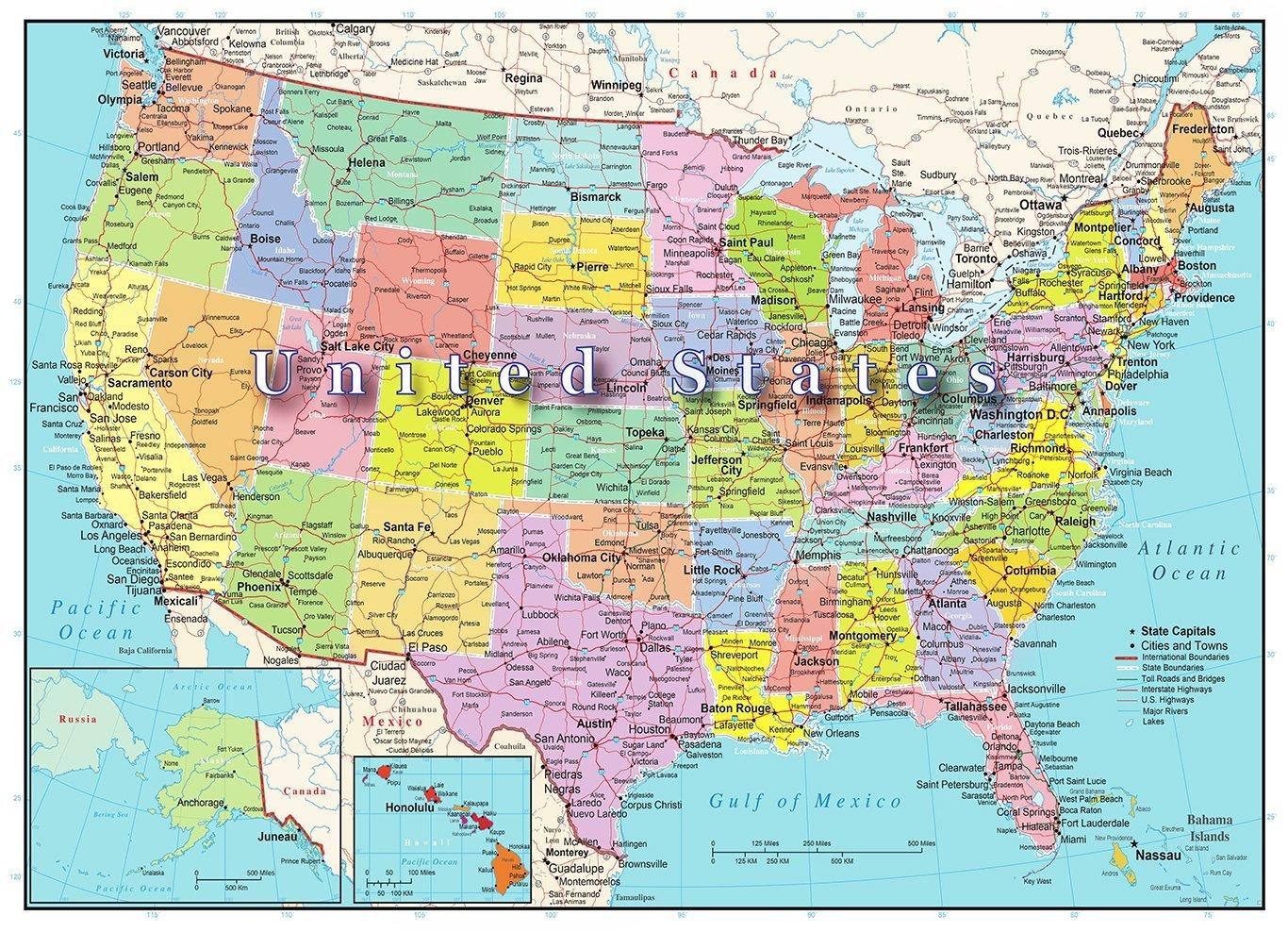

The geography of the American West is dominated by the "Basin and Range" province and the massive uplift of the Rockies. This isn't just a geology lesson. It dictates where the pavement actually goes. If you look at a western US map with roads, you’ll notice a massive amount of "white space" compared to the East Coast. That space isn't empty. It’s managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or the US Forest Service.

Honestly, the "roads" on these maps range from eight-lane interstates like I-80 to "roads" that are basically just two ruts in the dirt where a Jeep might struggle. You’ve got to know the difference. A standard highway map might show a line connecting two towns in rural Nevada, but it won't tell you that the "road" is sharp volcanic rock that will shred a passenger car tire in five miles.

Why Paper Still Wins in the Desert

Digital maps rely on pings. In the deep canyons of Zion or the shadows of the Sierra Nevada, those pings don't happen. A physical western US map with roads allows for "situational awareness" that a 6-inch phone screen can't match. You can see the relationship between the mountain ranges and the basins. You see that if you miss your turn on US-50 (the "Loneliest Road in America"), you might be driving 80 miles before you can legally and safely turn around.

The Benchmark Maps or DeLorme Atlases are the gold standard here. They use something called "land cover" shading. It shows you exactly where the forest begins and the scrubland ends. If you’re trying to find a dispersed campsite near the Grand Tetons, a standard Google Map is basically useless. You need a map that differentiates between a paved county road and a "high clearance" 4WD track.

💡 You might also like: Finding Your Way: The United States Map Atlanta Georgia Connection and Why It Matters

Understanding the Major Arteries

When we talk about a western US map with roads, the Interstates are the skeleton. I-5 runs the coast. I-15 slices from San Diego up through Salt Lake City and into Montana. I-25 hugs the Front Range of the Rockies. These are the fast lanes. They’re efficient, but they’re boring.

The real West is in the US Highways. The "Blue Highways," as William Least Heat-Moon called them.

- US-101: It’s the rugged, salt-sprayed sister to I-5. It hugs the coast and takes three times as long, but you actually see the Pacific.

- US-89: Often called the "National Parks Highway." It links Glacier, Yellowstone, Grand Teton, Zion, and Bryce Canyon. If you have one road trip in you, this is the one on the map to circle.

- US-395: The backbone of Eastern California. It runs along the base of the Sierra Nevada mountains. It’s arguably the most beautiful paved road in the country, passing by Mt. Whitney and Mono Lake.

Most travelers make the mistake of sticking to the purple lines (Interstates). Big mistake. Huge. If your western US map with roads shows a winding red or gray line that follows a river, take it. That’s where the actual scenery lives.

The "Secret" Layers: Public Lands and Topography

What most people get wrong about a western US map with roads is ignoring the colors behind the lines. In the West, who owns the land matters.

Yellow usually means BLM land.

Green is National Forest.

Purple or Pink is often Indian Reservations.

📖 Related: Finding the Persian Gulf on a Map: Why This Blue Crescent Matters More Than You Think

Why does this matter for your drive? Because you can usually camp for free (dispersed camping) on BLM and Forest Service land. You can't do that on private land or in most National Parks without a permit. If you're using a map like OnX Offroad or a printed Benchmark Atlas, you can see these boundaries. It changes how you travel. It turns a "drive" into an "expedition."

The Topography Trap

Let's talk about elevation. A flat map is a lie. If you're looking at a western US map with roads in Colorado, a 20-mile stretch of road might look like it takes 20 minutes. But if those 20 miles include a 12,000-foot pass with 15 switchbacks, it’s going to take you an hour. Maybe more if you're behind a rental RV with smoking brakes.

You need to look for contour lines or relief shading. If the road looks like a pile of dropped spaghetti, check your fuel gauge. Climbing uses more gas. Coming down uses more brakes. The West eats unprepared vehicles for breakfast.

Weather: The Map’s Silent Partner

A map might show a road, but the weather decides if it exists that day. Tioga Pass in Yosemite (Highway 120) is a major artery on any western US map with roads. But it’s closed. Every year. From roughly November to late May or even June.

I’ve seen people try to GPS their way from Lee Vining to Yosemite Valley in April, and the computer tells them it’s a two-hour drive. It’s not. It’s an eight-hour detour around the mountains because the road on the map is under 20 feet of snow. Always cross-reference your map with state DOT sites like Caltrans or WYDOT. They have live maps that show closures and chain requirements.

👉 See also: El Cristo de la Habana: Why This Giant Statue is More Than Just a Cuban Landmark

Navigating the "Dead Zones"

There are places in the West where the map says there's a town, but the town is a ghost. It might have a name on the map—places like Cisco, Utah, or Bitter Creek, Wyoming—but there is no gas. There is no water. There is no cell service.

If your western US map with roads shows a stretch of 100 miles without a significant town name, you better have a full tank. The "No Services for 80 Miles" signs are not suggestions. They are warnings. In the Great Basin, the distance between reliable help can be life-threatening if you break down in the summer heat or a winter blizzard.

Practical Steps for Your Western Journey

- Buy a physical Atlas. Specifically, get the Benchmark Road & Recreation Atlas for the specific state you’re visiting. They are vastly superior to Rand McNally for the West because they show public land boundaries.

- Download offline maps. If you use Google Maps or Gaia GPS, download the entire state or region before you leave the hotel Wi-Fi. Do not assume you'll have 5G in the mountains.

- Learn to read "LRS" (Linear Referencing System). Look for mile markers. In the West, many directions are given as "Turn south at mile marker 42."

- Check the "Shaded Relief." If the map looks bumpy in a certain area, plan for slower travel times.

- Verify the road surface. If a road on the map is a thin dashed line, it's likely unpaved. Don't take a rental Sentra on a dashed line in the San Rafael Swell.

The West is a place of scale. It’s a place where the map is an invitation to get lost, but only if you know how to find your way back. Get a real western US map with roads, put it on the hood of your car, and actually trace the route with your finger. It changes how you see the world. You start seeing the gaps between the towns not as empty space, but as the whole point of the trip.

Stop looking at the little blue dot on your phone. Look at the landscape. The map is just the legend for the story you’re about to write. Go find a road that doesn't have a name, just a number, and see where it ends. That’s usually where the best stuff happens anyway.