You’re standing on a curb at 11:00 PM. The rain is starting to blur your windshield. Your phone says "You have arrived," but the dark row of suburban houses in front of you looks like a wall of identical shadows. None of them have visible lights on their porches. You’re looking for 412, but the house to your left is 408 and the one to the right is... 420? In that moment, a map of house numbers isn't just a niche data point. It’s the difference between getting your pizza hot and wandering into a stranger's backyard by mistake.

Digital mapping has gotten scary good at showing us the curves of the earth and the traffic on the I-95. But once you zoom in past the street level, things get weirdly messy.

Most people assume Google or Apple just "knows" where every front door is. They don't. Mapping the world down to the individual structure—a process often called "sub-addressing" or "rooftop geocoding"—is one of the most expensive and frustrating challenges in modern geography. It’s a mix of government bureaucracy, high-resolution satellites, and literally paying people to drive around and look at stuff.

The messy reality of how house numbers actually work

We like to think of addresses as logical. We assume they follow a mathematical progression. But address systems were often created by local clerks in the 1800s or 1920s who were more worried about the local tax rolls than whether a GPS would find the place a century later.

In some parts of Queens, New York, house numbers use hyphens, like 18-34. In parts of Utah, the entire state is mapped on a massive grid centered on the Salt Lake Meridian, leading to addresses like 400 South 200 West. Then you have the "back house" problem. Or the "unit B" that sits behind "unit A" but shares the same driveway. If you are building a map of house numbers, these aren't just edge cases. They are the daily reality.

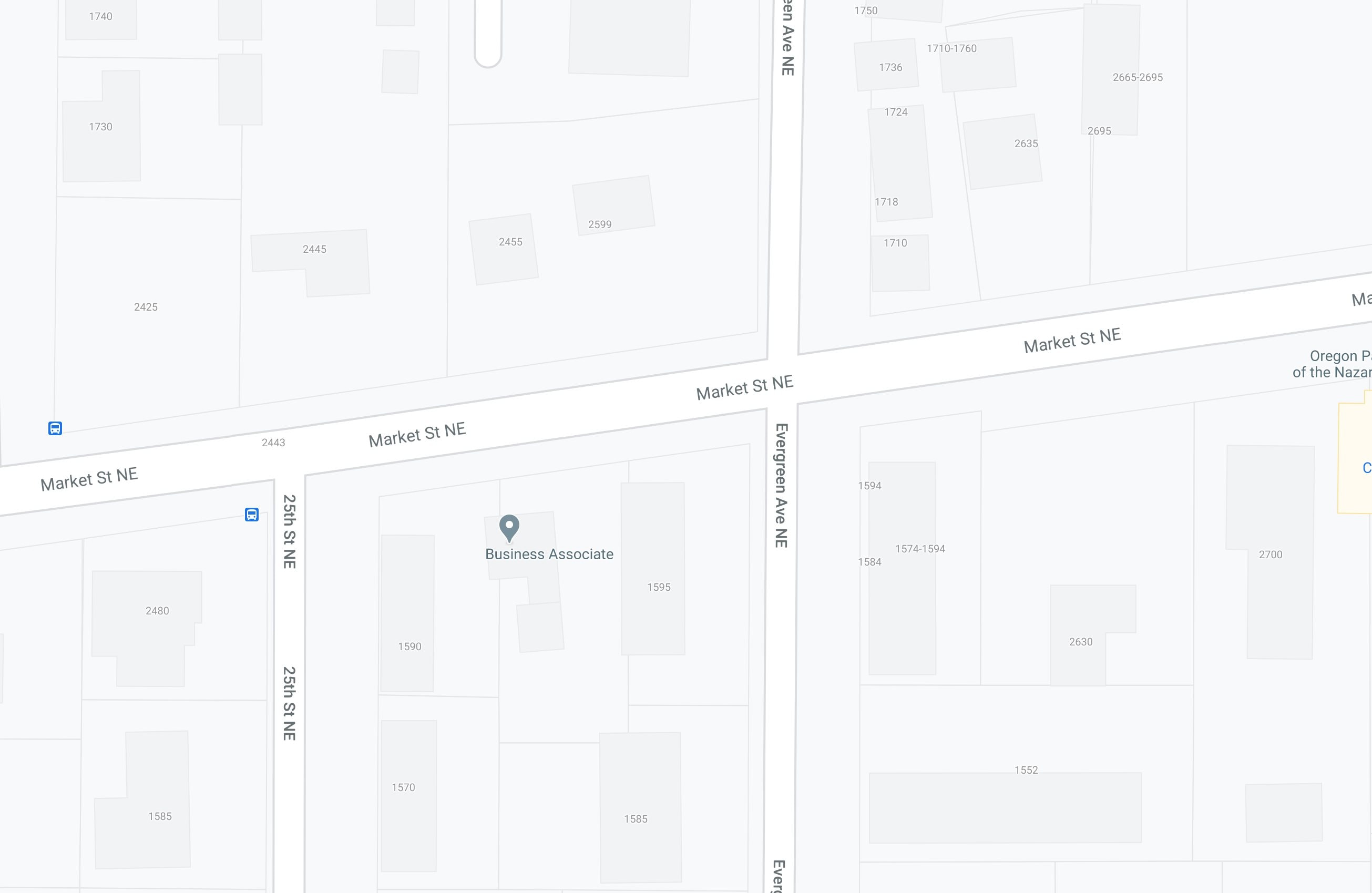

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is probably the most fascinating place to see this struggle in action. It’s the Wikipedia of maps. Thousands of volunteers spend their weekends tracing building footprints from satellite imagery and manually tagging them with house numbers. It’s a labor of love, but it’s also the most accurate data we have in many rural areas where the big tech companies haven't bothered to send a Street View car in five years.

👉 See also: Astronauts Stuck in Space: What Really Happens When the Return Flight Gets Cancelled

Where the data actually comes from

You can’t just buy a single file that contains every house number in the world. It’s fragmented.

First, there’s the TIGER data from the U.S. Census Bureau. It’s a foundational piece of the puzzle, but it’s often "interpolated." This means the computer sees that one end of a block is number 100 and the other end is 200. It then just guesses that number 150 is exactly in the middle. If there’s a vacant lot or a massive park in the middle of that block, the "guess" is wrong. Your GPS tells you that you've arrived, but you’re actually 300 feet away from the actual house.

Then you have County Assessor records. These are the "gold standard" for accuracy because they are tied to property taxes. If the government wants to collect money, they make sure they know exactly where the property sits. Companies like Esri or Mapbox often ingest this local government data to sharpen their maps.

But even then, a lot of it is just boots on the ground.

- Postal workers: The USPS has the most accurate list of where mail actually goes, but they don't always share the exact GPS coordinates of the front door with the public.

- Delivery drivers: Every time a DoorDash or Amazon driver hits "delivered," they are inadvertently helping "train" the map. If five drivers all stop at the same set of coordinates for 412 Oak St, the algorithm learns that the previous data point was slightly off.

- LiDAR and AI: Modern mapping cars use lasers to "see" the numbers on the side of a house. This is how Google can sometimes tell you exactly which side of the street your destination is on before you even turn the corner.

Why your GPS still gets it wrong

Ever had a delivery driver call you because they’re at the house behind yours? This usually happens because of "point-to-address" errors.

✨ Don't miss: EU DMA Enforcement News Today: Why the "Consent or Pay" Wars Are Just Getting Started

If a map of house numbers places the "pin" in the center of a large rural lot, the routing algorithm just tries to find the closest road to that pin. If your house sits on a 5-acre lot and happens to be closer to the back fence than the front driveway, the GPS will lead the driver to the street behind your house. It’s a "nearest neighbor" problem in geometry that causes thousands of missed deliveries every day.

We also have the "New Construction" lag. It can take six months to a year for a new subdivision to show up on a consumer-grade map. The developer assigns numbers, the city approves them, but the satellite hasn't flown over lately to see the new roofs.

The role of "Plus Codes" and What3Words

Because the traditional map of house numbers is so broken in many parts of the world—think of the favelas in Brazil or rural villages in India—new systems are trying to bypass numbers entirely.

Google’s "Plus Codes" are basically a digital address based on latitude and longitude. It looks like a short string of characters (e.g., 85GH+FH). It doesn't care about street names. It doesn't care about what the local council decided in 1950. It just marks a specific 3-meter by 3-meter square on the planet.

This is technically superior. It's precise. But humans hate it. We like names. We like "The blue house on the corner of Maple." We aren't robots, and we aren't likely to start telling our friends to come over to "7JQ4+W2" for a barbecue anytime soon.

🔗 Read more: Apple Watch Digital Face: Why Your Screen Layout Is Probably Killing Your Battery (And How To Fix It)

How to fix your own house on the map

If you live in a "ghost" house that delivery drivers can never find, you don't have to just live with it. You can actually edit the map of house numbers yourself.

On Google Maps, you can right-click (or long-press on mobile) and select "Report a problem" or "Edit the map." You can literally drag the pin to your front door. It’s not an instant fix—a human or a very smart AI has to verify that you aren't just prank-moving your neighbor's house to the middle of a lake—but it works.

Apple Maps has a similar "Report an Issue" feature. If you use OpenStreetMap, you can go to the site, create an account, and manually add your house number. Because so many other apps (like Instagram, Facebook, and various fitness trackers) use OSM data, fixing it there has a massive "trickle-down" effect on the rest of the internet.

Actionable steps for better location accuracy

If you’re a business owner or a frustrated homeowner, waiting for the tech giants to catch up isn't your only option.

- Check the major "aggregators": Companies like Factual, Acxiom, and Infogroup provide the data that fuels many maps. If your house or business address is wrong there, it will keep reappearing on maps even after you "fix" it locally.

- Verify your "Entrance Point": Some map editors allow you to set the "routing point" separately from the "house point." This tells the GPS exactly where the driveway starts, rather than just where the chimney is.

- Use physical signage: It sounds old-school, but in an age of digital mapping, high-contrast, reflective house numbers are more important than ever. If the GPS gets the driver within 50 feet, the physical sign has to do the rest of the work.

- Claim your business profile: If you’re running a shop, claiming your Google Business Profile and Bing Places for Business is the only way to ensure your address is treated as "verified" rather than just a guess.

The digital map of house numbers is a living, breathing thing. It's never "finished." As cities grow and suburbs sprawl, the data gets messy, decays, and has to be rebuilt. We are currently in the middle of a massive shift from "street-level" mapping to "door-level" mapping, and while it’s still glitchy, the days of wandering the rain looking for number 412 are slowly coming to an end.