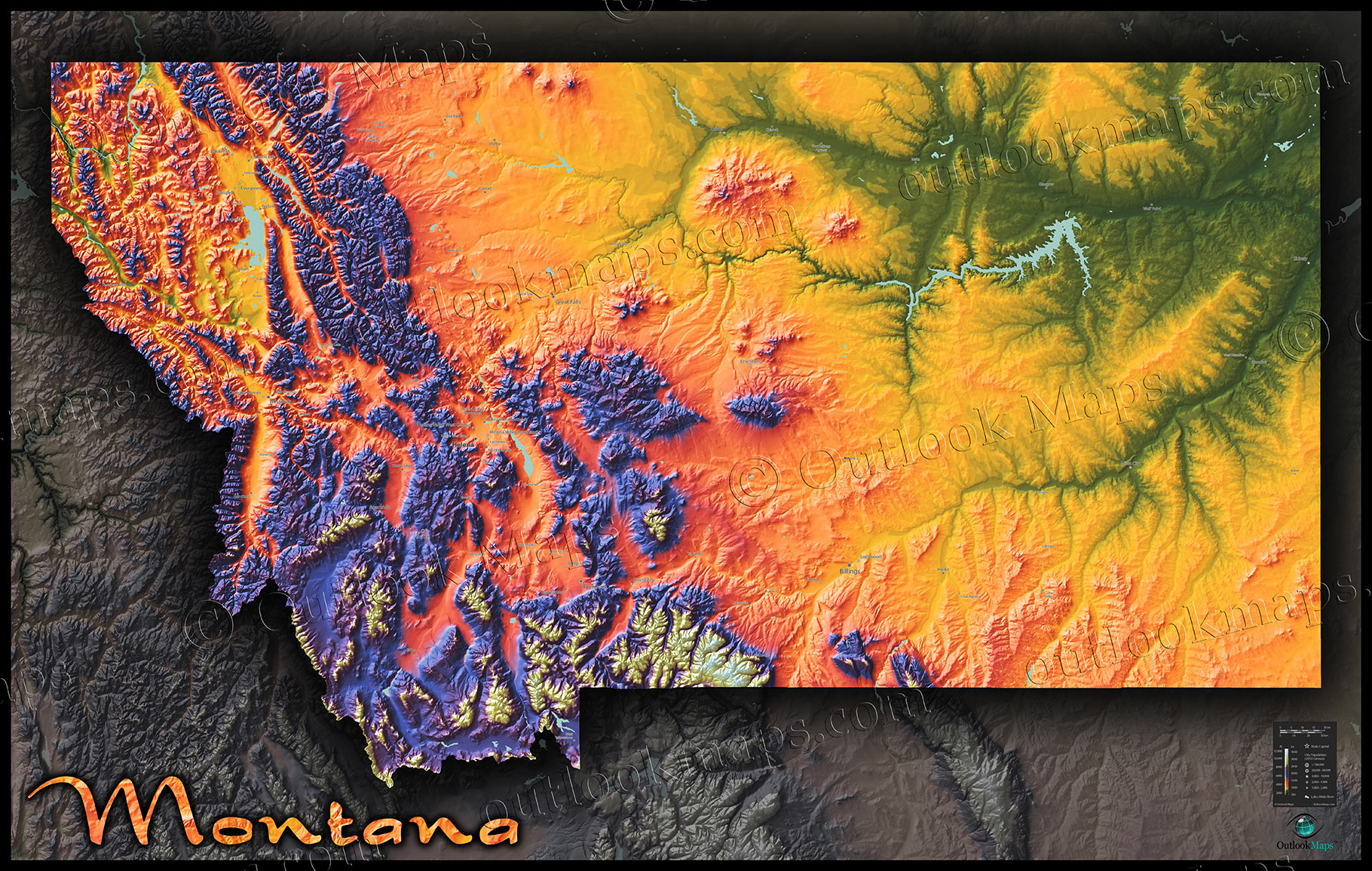

Montana isn't flat. That sounds like a "well, duh" statement until you’re standing at the bottom of a 2,000-foot scree slope in the Bitterroots with a heavy pack and a fading sunset. If you’ve ever stared at a topographic map of Montana and felt like you were looking at a bowl of brown spaghetti, you aren't alone. Those wiggly lines—contour lines, for the pros—are the only thing standing between a world-class backcountry experience and a very long, very cold night spent wondering where you went wrong.

The Big Sky State is a geometric nightmare. In the east, you have these vast, rolling plains that look simple but hide deep, deceptive coulees. Then, the ground basically explodes into the Rocky Mountains. Most people think they understand the terrain because they’ve seen the postcards of Glacier National Park. Real Montana is weirder than that. It’s a mix of high-desert plateaus, jagged limestone reefs, and river valleys so wide you can’t see the other side through the summer haze. Understanding the map is about more than just not getting lost; it's about reading the history of the earth written in 40-foot intervals.

Why the Topographic Map of Montana is Deceptive

Distance in Montana is a lie. On a standard road map, two points might look five miles apart. On a topographic map of Montana, you might realize those five miles involve crossing three separate drainages and a ridgeline that sits at 9,000 feet. The sheer scale of the vertical relief here is what catches newcomers off guard.

Take the Crazy Mountains. They rise abruptly out of the plains like a mistake. One minute you’re in wheat fields at 4,000 feet, and the next, you’re looking at summits over 11,000 feet. If you’re looking at a USGS 7.5-minute quadrangle map of this area, the contour lines are so tightly packed they almost blur into a solid block of ink. That "ink" is a cliff. You can't walk up that. You’ve gotta find the breaks, the saddles, and the gentler spurs that the map reveals only if you know how to squint.

Honestly, the "flat" parts of the state are sometimes harder to navigate. In the Missouri Breaks, the topography is fractured. It's a labyrinth of gumbo clay and eroded sandstone. A topo map here shows a mess of tiny, erratic circles and V-shapes indicating seasonal washouts. Without a map, you could walk in circles for days in a canyon that's only fifty feet deep but a hundred miles long.

Decoding the Colors and Symbols

We usually think of maps as green for forests and white for everything else, but Montana maps use color to tell a story of survival. On a modern USGS topo, that green tint represents "vegetation thick enough to hide a troop of soldiers." In Montana, that often means lodgepole pine so thick you have to crawl through it. If you see a white patch on a high-altitude map, it’s not just "open space." It's likely a rock field or alpine tundra.

🔗 Read more: Entry Into Dominican Republic: What Most People Get Wrong

Water is a Moving Target

Montana's hydrography is a huge part of its topographic identity. Blue lines on the map are supposedly rivers or creeks. In July? Sure. In September? That blue line might be a dry bed of fist-sized rocks. Experts look for the "perennial" vs. "intermittent" symbols—solid blue lines versus dashed ones. If you’re planning a trek through the Bob Marshall Wilderness, knowing the difference is the difference between a hydrated camp and a very dry, miserable hike.

The Magic of the Bench

One thing you’ll notice on a topographic map of Montana is the "bench." These are flat elevated areas above river valleys. They’re a classic Montana landform. Ranchers love them. Elk love them. And if you’re looking for a place to pitch a tent where you won’t roll into a creek in your sleep, you’re looking for where those contour lines suddenly spread out wide on a shoulder of a mountain.

The Continental Divide: The Ultimate Map Feature

You can't talk about Montana's shape without talking about the Divide. It snakes through the state like a jagged spine. On a map, this is the ultimate "high ground." It’s where the water decides if it wants to end up in the Pacific or the Gulf of Mexico.

Navigating the Divide is a masterclass in reading topographic maps. The peaks aren't just high; they're weather makers. When you see a "cirque" on the map—a U-shaped valley carved by a glacier—you're looking at a natural amphitheater. The lines will form a tight semi-circle. These areas often hold snow until August. If your map shows a tight cluster of lines on the north-facing slope of a peak, expect ice. Even in the middle of summer. I've seen hikers get trapped in "The Bob" because they assumed a pass was clear, ignoring the topographical reality that north-facing shadows create their own microclimates.

Where to Get the Best Data

Don’t just rely on your phone. Seriously. GPS is great until the battery dies or the cold kills your screen. In Montana, the cold will kill your screen.

💡 You might also like: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

- USGS Store: The gold standard. You can download the "US Topo" series for free as PDFs. They’re updated frequently and include layers for orthoimagery.

- Montana State Library (NRIS): This is the secret weapon for locals. The Natural Resource Information System has incredible GIS data. You can find maps that show land ownership—crucial because Montana is a checkerboard of public and private land.

- Avenza Maps: This app lets you use those USGS PDFs with your phone's GPS even when you have zero cell service. It’s how most search and rescue teams operate these days.

- OnX Backcountry: Founded right in Missoula. Their maps are specifically tuned for Montana's terrain, showing every trail, old logging road, and, most importantly, who owns the dirt you're standing on.

Misconceptions About Montana's Height

People think the highest point is the most important thing on the map. It's usually not. Granite Peak is the highest at 12,807 feet, located in the Beartooth Range. But look at the topo map for the Beartooth Plateau. It’s not just one peak; it’s a massive, high-altitude graveyard of rock. It’s the highest true plateau in North America.

The "saddle" is often more important than the "summit." A saddle is that low point between two peaks. On your topographic map of Montana, look for the hour-glass shape. That’s your gateway. If you’re trying to move from one drainage to another, you don't go over the top; you find the saddle. But be careful—wind screams through those saddles. If the contour lines are tight on either side of the saddle, you’re in a funnel.

The Eastern Third: Not Just a Flat Line

Most people blast through Eastern Montana on I-94 and think it’s a boring wasteland. Look at a topo map of the Makoshika State Park area near Glendive. It looks like the surface of the moon. The "Badlands" topography is a vertical nightmare on a small scale. You might only be moving up and down 100 feet at a time, but you're doing it every fifty yards.

The "Island Ranges" also dot the eastern half. These are isolated mountains like the Highwoods, the Big Snowies, and the Pryors. They sit all by themselves in the middle of the prairie. Their topo maps are fascinating because they’re like little circular fortresses. One minute it’s flat, then—boom—you’re in a limestone canyon with 500-foot walls.

Practical Next Steps for Map Users

If you're serious about exploring Montana, stop looking at Google Maps' "terrain" view. It’s too smoothed out. It hides the cliffs. It hides the coulees. It hides the truth.

📖 Related: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

Go to the USGS website and search for the "7.5-minute quadrangle" for an area you think you know—maybe a local state park or a favorite fishing hole. Print it out. Take it with you. Look at the ground, then look at the lines. Try to find a "spur" (a ridge sticking out) and a "draw" (the little valley between spurs).

Once you can "see" the 3D shape of the land by looking at the 2D lines, Montana opens up. You start seeing routes that aren't on any trail map. You see where the elk are likely to be hunker down during a storm (usually on a leeward slope in a timbered draw). You see where the water has to be.

Before your next trip, check the "magnetic declination" on the bottom of your topographic map of Montana. In Montana, the difference between "true north" and "magnetic north" is significant—anywhere from 11 to 15 degrees East depending on where you are in the state. If you don't adjust your compass, you'll be a mile off your target by the end of the day. That's a lot of extra walking in a state that doesn't offer many shortcuts.

Grab a physical map. Study the drainages. Learn the difference between a ridge and a cliff. The terrain here is unforgiving, but the map tells you everything you need to know if you're willing to listen.