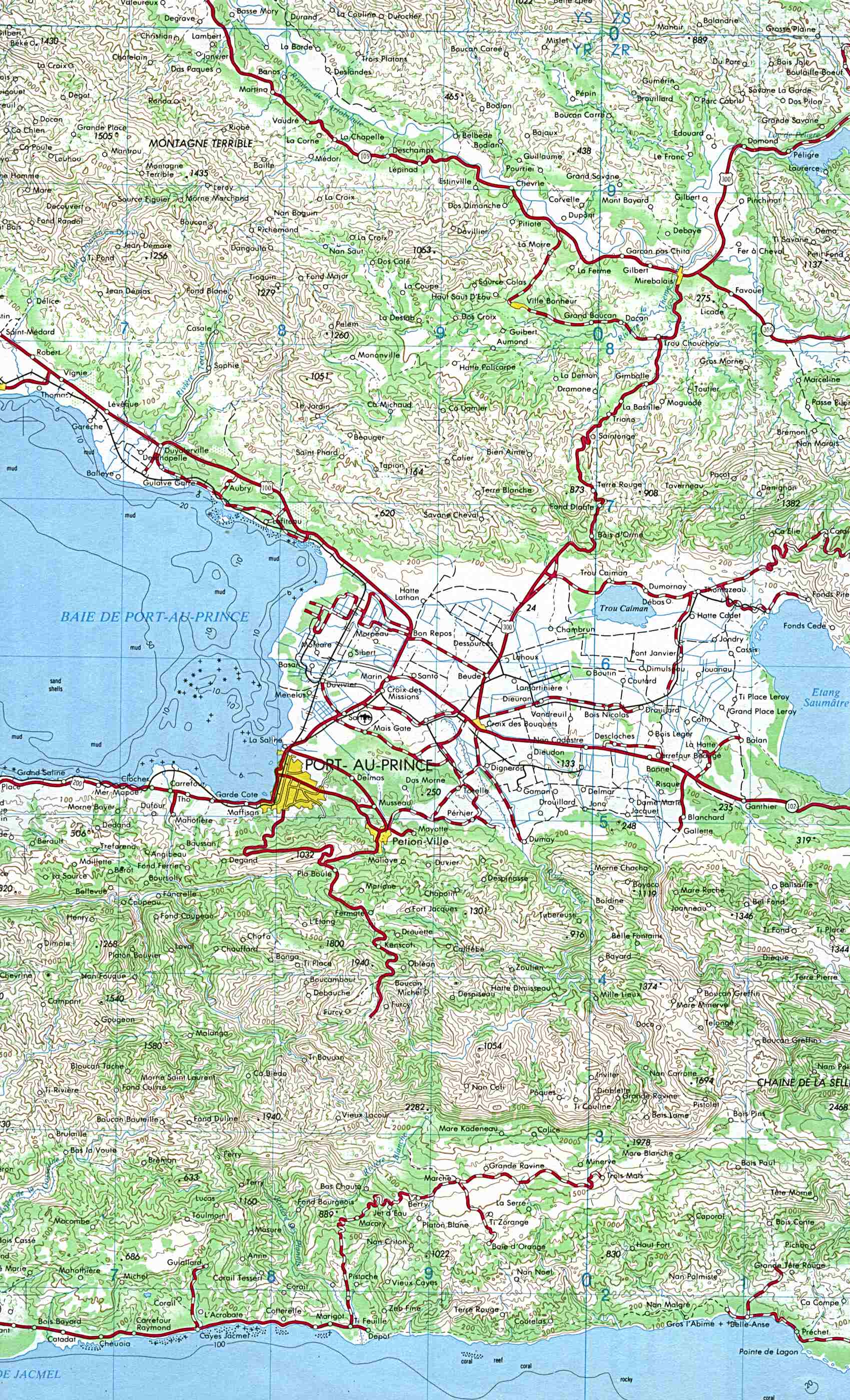

If you open a digital Port au Prince map right now, you’ll see a sprawling grid of gray lines, green patches labeled "Parc de Martissant," and a coastline that hugs the Gulf of Gonâve. It looks orderly. It looks static. But anyone who has actually walked the streets from Pétion-Ville down to the Iron Market knows that a map of Haiti’s capital is more of a suggestion than a rulebook.

Maps are liars, or at least, they’re chronically out of date in a city that breathes, shifts, and rebuilds itself every single week.

Navigation here is an art form. You aren't just looking for street names; you're looking for landmarks that might not exist in the way Google Maps thinks they do. In Port-au-Prince, "turn left at the big mango tree" or "stop before the colorful tap-tap station" are often more reliable directions than any GPS coordinate.

Navigating the Chaos of the Port au Prince Map

The geography of the city is dictated by the mountains. It’s basically a massive bowl. The "bottom" of the bowl is the downtown area, the Centre-Ville, which sits right at sea level. This is where the history is. It's where the National Palace—or what remains of its footprint—stands as a silent witness to the 2010 earthquake and the political turbulence that followed.

As you move up the rim of the bowl, you go higher in elevation and, generally, higher in socioeconomic status.

Pétion-Ville is the famous suburb perched on the hills. If you're looking at a Port au Prince map, you’ll notice the roads get windier and more serpentine as they climb toward Kenscoff. The air gets thinner. It gets cooler. You’ll see luxury hotels like the Karibe or the El Rancho. But even here, the map is deceptive. A road that looks like a major thoroughfare on your screen might actually be a narrow, potholed alleyway where two SUVs can’t pass each other without a ten-minute negotiation.

Then there’s the traffic. Blokis.

You can’t see blokis on a static map. A three-mile trip from Delmas to the airport can take twenty minutes or three hours. It depends on the time of day, whether a truck has broken down on the Route de l'Aéroport, or if there's a spontaneous street market spilling onto the asphalt.

The Evolution of the Grid

Historically, the city was designed with a colonial French flair. You can still see the remnants of that logic in the Place de l'Indépendance. But the 2010 earthquake fundamentally rewrote the city's DNA.

📖 Related: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

When the earth shook, the map broke.

Entire neighborhoods shifted. Internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, which started as temporary clusters of blue tarps, eventually turned into permanent settlements. Look at Canaan. North of the city, Canaan didn't really exist on a Port au Prince map before 2010. Now, it’s a massive, sprawling urban zone with its own internal logic, commerce, and navigation challenges.

Most digital mapping services are still trying to catch up with the sheer speed of informal urban development in areas like Jalousie. If you look at a satellite view of Jalousie, it looks like a vibrant, multicolored mosaic climbing the hillside. It’s beautiful in a way that defies traditional urban planning. But try finding a specific house number there? Good luck. You navigate by the color of the walls or the proximity to the local water tap.

Safety and the "Red Zones"

We have to be real about the current situation. Since 2021, and especially into 2024 and 2025, the Port au Prince map has become a checkerboard of "go" and "no-go" zones.

This isn't just about bad neighborhoods. It's about territorial control.

Organizations like the ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project) and local analysts often produce heat maps that show which gangs control which intersections. Areas like Cité Soleil, Martissant, and Fontamara are frequently highlighted. For a traveler or even a local, knowing where the "invisible borders" lie is more important than knowing the name of the street.

- The Airport Corridor: Generally the most heavily monitored and vital artery.

- The Pétion-Ville Ascent: Usually stays more accessible, but prone to kidnapping "hotspots" at certain intersections.

- The Downtown Core: A mix of vibrant commerce and high-risk zones that can change hour by hour.

Honestly, if you're using a map to get around, you need a "human" layer on top of the digital one. Check local WhatsApp groups or the "Ayiti Info" type alerts. They provide the real-time data that Google hasn't figured out how to automate yet.

Transport: The Tap-Tap Network

If you want to understand the city's layout, look at the tap-taps. These are the brightly painted pickup trucks and buses that serve as the city's primary transit system. They don't have a published map in the way a Londoner has a Tube map.

👉 See also: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

Instead, they have "stations."

A tap-tap might be labeled "Carrefour" or "Delmas." You hop on, pay a few gourdes, and bang on the side of the truck when you want to get off. The "map" of the tap-tap routes is etched into the collective memory of the population. It’s a decentralized, self-organizing system that works surprisingly well, even when the main roads are blocked.

Understanding the Landmarks

When you're staring at your phone, trying to make sense of the Port au Prince map, look for these anchors. They help orient your brain when the street signs are missing.

The Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption: Or rather, the ruins of it. It remains a hauntingly beautiful landmark in the downtown area. It’s a waypoint. If you're near the Cathedral, you’re in the heart of the old city.

The Iron Market (Marché en Fer): It’s bright red. It’s iconic. It was shipped from France in the late 19th century—originally destined for a railway station in Cairo, or so the story goes. It’s the chaotic, pulsing center of Haitian commerce. On a map, it’s a rectangle. In reality, it’s a sensory overload of spices, metalwork, and shouting.

MUPANAH: The Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien. It’s mostly underground, located across from the National Palace. It’s one of the few places where the map stays consistent because the grounds are well-maintained and highly guarded. It’s a great "reset" point if you get lost downtown.

The Problem with Digital Mapping in Haiti

Why does Google Maps struggle here?

Infrastructure.

✨ Don't miss: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

In many Western cities, the map is built on top of stable municipal data. In Port-au-Prince, the data is fragmented. OpenStreetMap (OSM) actually does a better job in many parts of Haiti because it relies on "crowdsourced" intelligence. After the earthquake, thousands of digital volunteers around the world used satellite imagery to trace every building and footpath, creating the most detailed Port au Prince map in existence.

Even then, a map cannot tell you about road quality. It won't tell you that a "primary road" is currently underwater because of a clogged drainage canal after a tropical storm. It won't tell you that a bridge is out.

You have to drive with your eyes, not just your screen.

Practical Advice for Navigating the City

If you’re heading to Haiti—or if you're trying to coordinate logistics from afar—don't rely on a single source.

- Download Offline Maps: Data can be spotty. Download the entire Port-au-Prince area on Google Maps or use an app like Maps.me which uses OSM data.

- The "Rule of Two": If you're driving, always have two routes planned. The "direct" route on your Port au Prince map might be blocked by a protest, a market, or a construction project that started five minutes ago.

- Ask a "Mototaxi": The guys on the small motorbikes (motos) are the masters of the city’s geography. They know every shortcut, every back alley, and every road closure. If you’re stuck, follow a moto.

- Identify the Communes: Port-au-Prince isn't just one giant blob. It’s a collection of communes: Delmas, Cité Soleil, Pétion-Ville, Carrefour, Tabarre. Each has its own vibe and its own level of "mappability."

The Future of the Map

There is a movement toward "smarter" mapping in Haiti. Local tech hubs and NGOs are trying to map the "informal" economy. They are documenting where the solar streetlights are, where the clean water points are, and where the nearest medical clinics sit.

This isn't just about finding a restaurant. It's about survival and urban resilience.

A map of Port-au-Prince is a living document. It reflects the struggle, the creativity, and the sheer will of a people who refuse to be defined by the disasters that have crossed their borders. When you look at that map, don't just see the streets. See the layers of history, the heights of the mountains, and the complex social web that keeps the city moving even when the "official" systems fail.

Actionable Next Steps for Travelers and Researchers:

- Cross-Reference with Satellite Views: Always toggle to "Satellite" mode on your digital map. This allows you to see the actual terrain and building density, which is often more helpful than the stylized "Map" view in Port-au-Prince.

- Use OpenStreetMap (OSM): If you are doing any kind of logistics or humanitarian work, use OSM-based tools. They are significantly more detailed regarding footpaths and smaller structures in the informal settlements.

- Monitor Local News Feeds: Before setting out on any route shown on your Port au Prince map, check local social media or radio stations (like Radio Métropole) for "état de la route" (road conditions) updates to avoid unexpected delays or safety issues.