If you open a digital Port au Prince map Haiti right now, you aren’t just looking at streets. You’re looking at a grid of survival, shifting borders, and a city that refuses to be defined by a static GPS coordinate. Most people look at the map and see a chaotic sprawl. But there’s a logic to it, even if that logic is currently dictated by security perimeters and neighborhoods that change hands overnight.

It’s complicated.

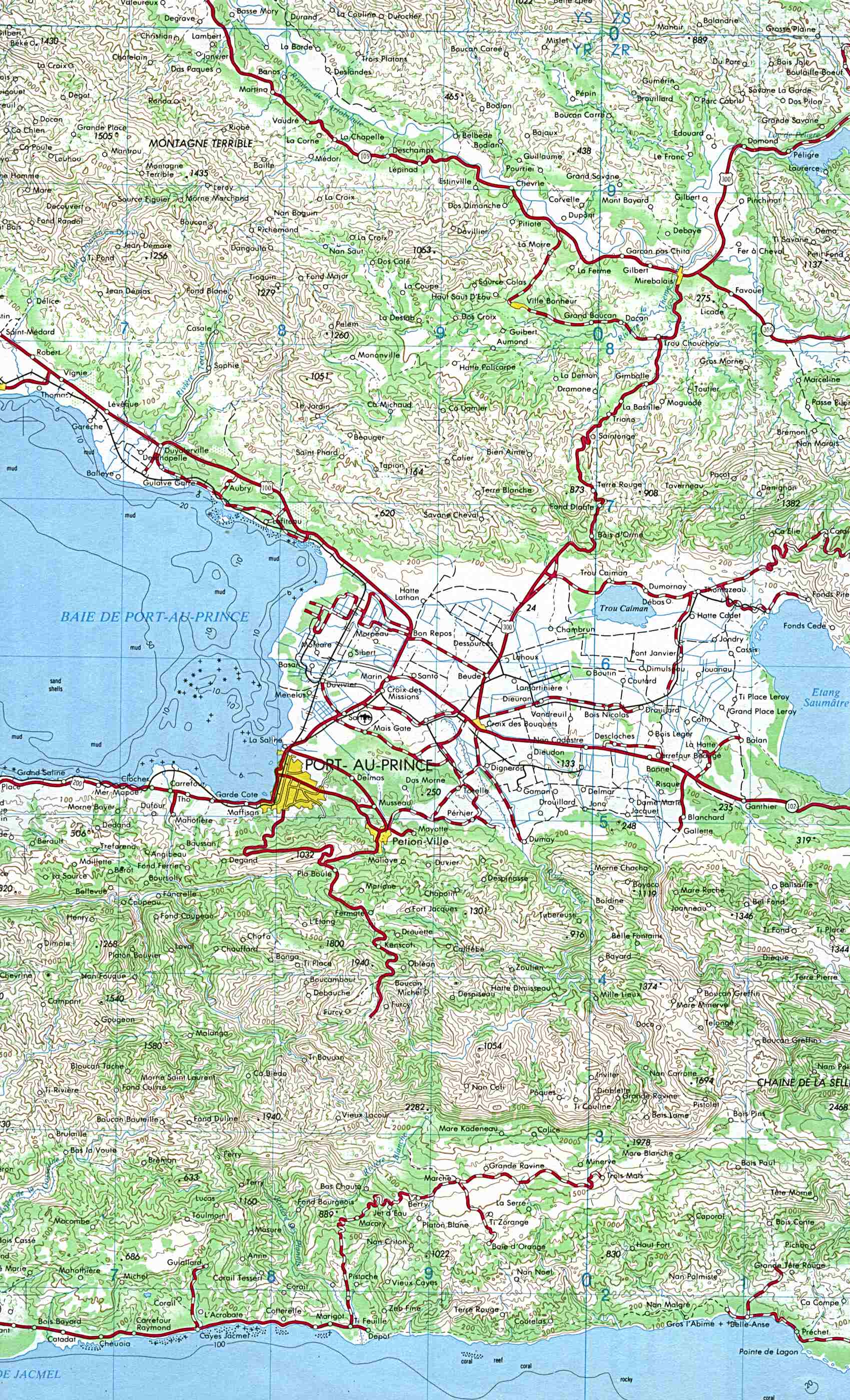

Port-au-Prince wasn't built for three million people. It was designed for a fraction of that, nestled into a coastal bowl where the mountains of the Massif de la Selle meet the Gulf of Gonâve. When you look at the layout, you see the history of French colonialism in the "Bas-Peu-de-Chose" district and the modern desperation in the vast stretches of Cité Soleil. To understand the map is to understand why the city breathes the way it does.

The Geography of Power and the Port au Prince Map Haiti

Street maps are mostly liars in Port-au-Prince lately. You see a road marked "Boulevard Toussaint Louverture," and on paper, it’s the main artery to the airport. In reality? It’s a gauntlet. The physical geography of the city is dominated by two things: the waterfront and the hills.

The wealthy moved up. It’s that simple. As you move south and east on the map, the elevation climbs toward Pétion-Ville. The air gets cooler, the roads get narrower, and the "map" starts to look more like a series of fortified islands. Meanwhile, the "bottom" of the city—the downtown area near the National Palace—has become a literal no-go zone.

Why the Downtown Core Disappeared

The National Palace sits (or sat, rather, as the ruins of the 2010 earthquake were eventually cleared) at the symbolic heart of the Port au Prince map Haiti. Around it, you have the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption and the main government buildings.

But here’s the thing.

If you tried to walk those streets today, you’d find a ghost town. The iron market (Marché en Fer) is a masterpiece of 19th-century design, but the "map" doesn't show you the barricades. The gangs—specifically the Viv Ansanm coalition led by figures like Jimmy "Barbecue" Chérizier—effectively rewrote the city's topography. They didn't just take over buildings; they took over the intersections. In mapping terms, they control the "nodes." If you control the intersection of Route de Delmas and the airport road, you control the country’s windpipe.

Navigating the "Red Zones"

Most humanitarian organizations, like the UN’s OCHA or Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), use a version of the Port au Prince map Haiti that looks like a heat map of risk.

It’s basically a checkerboard.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened When 10 People Died in the Bronx Last Night

- Cité Soleil: This is the largest slum in the Western Hemisphere. On a standard Google Map, it looks like a dense grid near the northern coast. In reality, it’s a series of "fronts" between rival factions.

- Martissant: This neighborhood is the gatekeeper to the south. If Martissant is blocked—which it has been, off and on, for years—the entire southern peninsula of Haiti is cut off from the capital.

- Delmas: This is a massive corridor. It’s divided into "numbers" (Delmas 32, Delmas 75). It’s the commercial spine of the city.

The hills aren't safe anymore, either. Neighborhoods like Laboule and Thomassin, once considered elite retreats, are now frequently highlighted on security maps as high-risk areas for kidnapping. The map has expanded. The violence has moved uphill.

The Infrastructure Gap

Let’s talk about the actual "stuff" on the map. Port-au-Prince has a severe lack of paved roads for its density. When you look at the Port au Prince map Haiti, you see a few thick yellow lines—Route Nationale 1 going north, Route Nationale 2 going south. That’s it. There are no bypasses. No ring roads.

This is a geographical trap.

If one truck breaks down on the road through Martissant, the whole city chokes. If a gang sets up a checkpoint on the road to Mirebalais, the center of the country loses its connection to the coast. It’s a fragile system. We’re talking about a city where the "map" is often just a list of bottlenecks.

The 2010 Earthquake and the Map That Never Was

We have to mention the earthquake. It’s been over fifteen years, but the Port au Prince map Haiti is still a post-seismic document.

Before 2010, the city was dense. After 2010, it exploded outward. Look at the area called Canaan. It’s north of the city. Before the quake, it was empty, dusty land. After the quake, tens of thousands of people moved there because they had nowhere else to go. Now, it’s a permanent city. But it’s a city without a plan.

Canaan is the "accidental" part of the map. It wasn't designed by urban planners in suits. It was built by people with cinderblocks and grit. When you see it on a satellite map, the sprawl is staggering. It stretches for miles along the coast, a testament to Haitian resilience and the total failure of formal housing projects.

How People Actually Get Around

Forget the map for a second. If you want to move in Port-au-Prince, you use a tap-tap.

These are brightly painted pickup trucks and buses. They are the blood cells of the city. They don't follow a printed map you can buy at a kiosk. They follow "stations." You go to the station at Portail Léogâne to go south. You go to the station at Clercine for the airport.

Honestly, the tap-tap routes are the real map of the city. They tell you where the people are, where the markets are open, and where the "boundaries" are currently respected. If the tap-taps aren't running to a certain neighborhood, that neighborhood is "off the map" for that day.

Digital Mapping and OpenStreetMap (OSM)

When the 2010 quake hit, the "official" maps were useless. That’s when the OpenStreetMap community stepped in. In what became a landmark moment for digital geography, thousands of volunteers worldwide used satellite imagery to trace every building and alleyway in Port-au-Prince.

Today, the most accurate Port au Prince map Haiti isn't from a government office—it’s the OSM data.

- It tracks the growth of informal settlements.

- It marks water points and clinics.

- It is updated by locals who know when a bridge is out or a new market has formed.

Google Maps is okay for the main roads, but if you need to find a specific "impasse" in a neighborhood like Bel-Air, you’re better off with OSM or asking a local. GPS coordinates in Haiti are often "near the big mango tree" or "behind the blue church."

The Ports and the Airport: The Map’s Last Stand

The port (APN) and the Toussaint Louverture International Airport are the most vital points on the Port au Prince map Haiti.

🔗 Read more: Who is Robert Lee: The Civil War General, the ESPN Sportscaster, and the CEO Changing New York

They are the lungs.

Haiti imports almost everything, including its food. The port is located right in the middle of some of the most contested territory in the city. To get a shipping container out of the port and into the city, you have to cross through multiple zones of influence.

The airport is on the northern edge. It’s a massive plot of flat land. In early 2024, the "map" of the airport became a literal battlefield. Gangs tried to breach the perimeter walls. The map shows a runway; the reality was a fortress under siege. When the airport closes, the map of Haiti becomes an island within an island. You can’t leave. You can’t get help.

The Role of Topography

Why don't the police just "take back" the city? Look at the map again.

Port-au-Prince is a maze of "ravines." These are deep, narrow gullies that run from the mountains down to the sea. They act as natural drainage for rain, but they also act as hidden highways for anyone who knows them.

You can move an entire group of people across the city through these ravines without ever stepping onto a "mapped" road. It makes traditional policing almost impossible. The geography favors the insider. It favors the person who knows the dirt paths, not the person looking at a digital screen.

Practical Realities for Travelers and Expats

If you find yourself needing to use a Port au Prince map Haiti for actual navigation, you need to throw out everything you know about driving in a city like Miami or Paris.

- Don't trust the "shortest route." The shortest route might take you through a neighborhood that is currently in a state of "lock."

- Check the morning news. Local radio stations and WhatsApp groups are the real-time updates for the map. They will tell you if a "barrikad" (barricade) has been erected on a major road.

- Elevations matter. If it rains, the "bottom" of the map floods instantly. The drainage is poor, and the garbage often clogs the canals. A 10-minute drive can become a two-hour wade.

- Privacy is a myth. Many streets on the map look like public thoroughfares but are treated as private territory by the locals who live there.

The Future of the City Layout

There are talks of "decentralizing" the map. Some people want to move the administrative center of Haiti away from Port-au-Prince entirely. Maybe to the Central Plateau.

It’s a dream, mostly.

Port-au-Prince is too deep. Too historical. Too vital. You can’t just "move" a city of three million. The map will likely continue to densify. We will see more vertical growth in the hills and more "informal" expansion in the north.

The map of Port-au-Prince is a living document. It’s scarred, yes. It’s messy. It’s heartbreakingly difficult to navigate. But it’s also a map of a city that has survived coups, quakes, and colonial debt that would have crushed almost any other place on Earth.

📖 Related: Would Biden Have Done Better: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insights for Using the Map

If you are researching the Port au Prince map Haiti for academic, humanitarian, or travel reasons, keep these specific points in mind to stay grounded in reality:

- Use OpenStreetMap for detail: It is significantly more accurate than Google Maps for footpaths, small businesses, and neighborhood boundaries within the slums.

- Monitor the "Ti-Lalin" (Little Moon) markers: In local parlance, certain landmarks (like the "Carrefour de l'Aéroport") are the only way to orient yourself. Learn the names of the major "Carrefours" (intersections).

- Identify the "Green Line": This isn't an official term, but there is a clear elevation line (roughly around the 300m mark) where the urban heat and density begin to give way to the more ventilated, residential zones of the upper city.

- Consult Security Feeds: Use sources like the "Haiti Security Barometer" or UN satellite imagery to see how the "human map" is shifting. The physical streets stay the same, but the "usable" streets change daily.

- Respect the "Gwo Mòn": The mountains are beautiful, but they are also the "walls" of the city. Any movement toward the border with the Dominican Republic or the southern coast must take these massive geographical barriers into account. There are only a few passes. Know them.

The map of Port-au-Prince is more than just coordinates. It’s a story of a people who have been squeezed into a small space and forced to make it work. When you look at that screen, see the people, not just the lines.