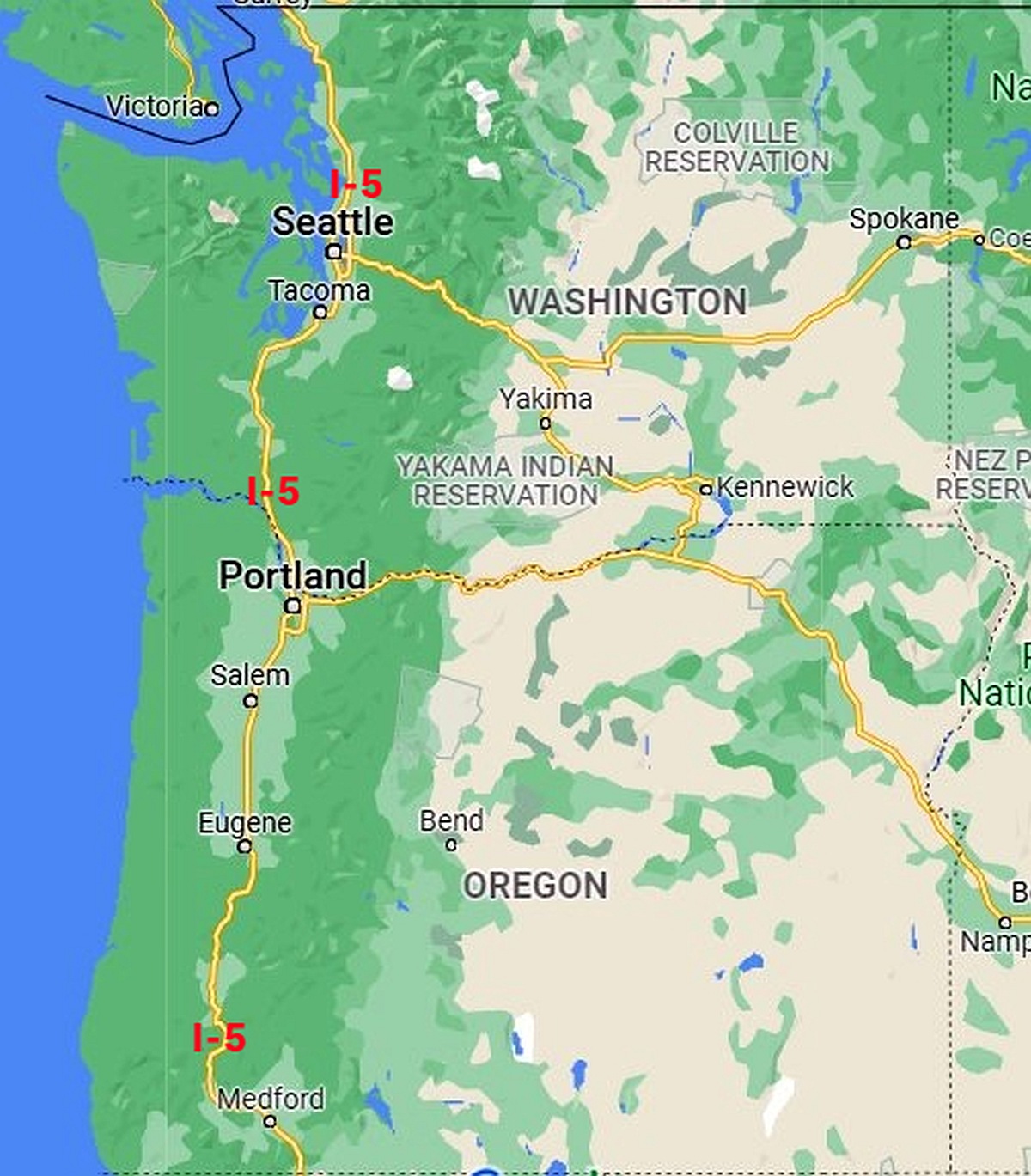

You’re looking at a map of Washington and Oregon. It looks simple enough on a screen, right? Two big blocks of the Pacific Northwest stacked like LEGO bricks. But if you’ve actually driven from the rainforests of the Olympic Peninsula down to the high desert of Alvord, you know that 2D representation is lying to you. Maps flatten the struggle. They hide the fact that a "two-hour drive" on paper can turn into a four-hour ordeal if the Chinook Pass is closed or if a logging truck is crawling up a grade in the Blue Mountains.

Most people treat these states as a package deal. I get it. They share the 45th parallel, a rainy reputation, and a love for hops. However, looking at a map of Washington and Oregon reveals a deep, topographical divide that dictates everything from where people live to why the air feels different the moment you cross the Columbia River.

The Vertical Spine: Why the Cascades Rule Everything

Check any relief map. You’ll see a jagged line of brown and white running north to south. That’s the Cascade Range. It isn't just a pretty backdrop for your Instagram photos of Mount Hood or Mount Rainier; it is a literal wall. This range creates a rain shadow that is one of the most dramatic climate shifts on the planet.

On the west side, you have the lush, moss-covered reality everyone expects. Seattle, Portland, Eugene, and Olympia sit in this green corridor. But slide your finger just an inch east on that map of Washington and Oregon, and everything changes. You hit the "dry side." Places like Yakima, Bend, and Pendleton are high deserts. They get more sun in a week than some coastal towns get in a month.

I’ve met travelers who planned a "scenic drive" through central Oregon in February, thinking it would be misty and cool. They ended up in a blizzard near La Pine because they didn't respect the elevation markers on their map. The Cascades aren't a suggestion. They are a gatekeeper.

The Columbia River Gorge: The Only Way Through

There is one major break in that mountain wall. It’s the Columbia River. If you look at the border between the two states, you’ll see the river carving a winding path. This is the only sea-level break in the Cascades. Because of this, the Gorge acts as a massive wind tunnel.

The pressure differences between the wet west and the dry east force air through that gap at incredible speeds. It’s why Hood River is the windsurfing capital of the world. It’s also why, when you’re driving I-84 or SR-14, your car might suddenly lurch to the side. The map shows a flat blue line, but the reality is a high-velocity corridor of basalt cliffs and whitecaps.

📖 Related: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

Navigating the Urban Growth Boundaries

If you are using a map of Washington and Oregon to plan a move or a long-term stay, you need to understand the "invisible" lines. Oregon, in particular, has strict Urban Growth Boundaries (UGBs). This was a landmark piece of legislation from the 1970s meant to stop suburban sprawl and protect farmland.

When you look at a satellite map of the Willamette Valley, you’ll see a sharp line where the houses stop and the grass seed farms begin. It’s not an accident. It’s why Portland feels so dense compared to sprawling cities like Phoenix or Houston. Washington has similar "Growth Management Act" rules, but they feel a bit different on the ground. Seattle’s geography—squeezed between Lake Washington and the Puget Sound—did a lot of the work that laws did in Oregon.

Honestly, it makes for a weird navigation experience. You can go from a high-rise tech hub to a muddy dairy farm in twenty minutes.

The Coast: A Tale of Two Policies

Public access. That’s the big one.

When you look at the map of Washington and Oregon coastline, they look identical. Rugged. Cold. Moody. But Oregon’s "Beach Bill" of 1967 means the entire 363-mile coastline is public. Every inch. You can’t own the dry sand in Oregon. In Washington, it’s a bit more of a patchwork. Some areas are private, and others are part of the Olympic National Park or tribal lands.

If you're planning a road trip, this matters. In Oregon, you can basically pull over anywhere there’s a gap in the trees and walk to the water. In Washington, especially around the Sound, you’ve gotta check the map for public access points or state parks like Deception Pass.

👉 See also: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

Why the "Olympic Peninsula" is a Map Trap

Look at the top left corner of Washington. That big circular bump? That’s the Olympic Peninsula. It looks like a quick day trip from Seattle.

It isn't.

Because of the Olympic Mountains (which sit right in the middle of the peninsula), there are no roads that go across it. You have to drive all the way around on Highway 101. It’s a massive time commitment. Many people look at the distance "as the crow flies" and think they can do Port Angeles and the Hoh Rain Forest in an afternoon. You can't. You'll spend six hours in the car just trying to bypass the mountains that the map makes look so small.

The "Other" Washington and Oregon

Most people ignore the eastern two-thirds of the map of Washington and Oregon. That’s a mistake.

The Palouse in Southeast Washington is one of the most beautiful sights in America. It’s a region of rolling silt dunes that look like a green and gold ocean. It’s world-class for photography. Then you have the Wallowa Mountains in Northeast Oregon, often called "Little Switzerland." These areas are rugged, remote, and vastly different from the rain-slicked streets of the I-5 corridor.

In these parts, the map becomes about survival and preparation. Cell service? Spotty. Gas stations? Maybe every 60 miles if you’re lucky. If you are heading out toward Steens Mountain or the Okanogan, your digital map might fail you. I always tell people to keep a physical gazetteer in the trunk. It sounds old-school, but when you're at the bottom of a canyon in the Owyhee Wilderness, Google Maps isn't coming to save you.

✨ Don't miss: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

Getting Specific: Key Points of Interest Often Missed

Don't just look for the big dots. The map of Washington and Oregon is full of anomalies that define the region's history.

- The Hanford Site: In Eastern Washington, there is a massive chunk of land near the Tri-Cities that is essentially a void on most casual maps. This was a key part of the Manhattan Project. It’s one of the most contaminated sites in the world, and while they do tours, it’s a sobering reminder of the region’s role in the Cold War.

- The Lost Forest: In the middle of the Oregon desert, there is a stand of Ponderosa pines that shouldn't exist. They are prehistoric leftovers from a wetter era, surviving on a fraction of the water they usually need. Finding it on a map requires some serious zooming.

- Point Roberts: Look at the very top of Washington, near Vancouver, BC. There is a tiny peninsula called Point Roberts. It’s part of the U.S., but it’s not connected to the mainland. To get there by land, you have to drive through Canada. It’s a geographic quirk that makes for some very weird border crossing stories.

Acknowledging the Limitations of the Grid

Maps are human inventions. They don't account for the "Big One." We are sitting on the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Geologically speaking, the map of Washington and Oregon is a work in progress. The coastline has changed over thousands of years and will change again. When you look at the Tsunami Evacuation maps posted along the coast, you realize how fragile these boundaries are.

Also, we have to talk about the political map. There is a growing movement in Eastern Oregon to "Move Oregon’s Border" and join Idaho. While it’s legally a long shot, it highlights the cultural rift that the physical map ignores. The lines we draw aren't always the lines people feel.

Actionable Insights for Your Next PNW Map Study

If you’re using a map of Washington and Oregon to plan a life or a trip, here is how to actually use the data:

- Check the Snow Levels, Not Just the Route: If you’re crossing the Cascades between October and June, your map route is meaningless if the passes are closed. Always cross-reference your map with the WSDOT or TripCheck (Oregon) apps.

- Calculate Time by Terrain: In the PNW, 50 miles on a highway is not the same as 50 miles on a coastal or mountain road. Double your time estimates for anything off the I-5 or I-84.

- The "Rain" Is a Lie: Don't let the "green" on the map fool you into thinking it's always pouring. July through September is often bone-dry. If you're camping, check the fire maps. In 2026, smoke maps are just as important as road maps.

- Download Offline Maps: Especially for the Olympic Peninsula, North Cascades, and the entirety of Eastern Oregon. You will lose LTE.

- Look for the Basalt: If the map shows a river, look for the word "Canyon" or "Gorge." The geology here is volcanic. Expect verticality.

The Pacific Northwest isn't just a place on a map; it's a series of vertical challenges, microclimates, and legal boundaries that define how we move through the world. Whether you're looking for the best Pinot Noir in the Dundee Hills or trying to find a remote trailhead in the Pasayten Wilderness, the map of Washington and Oregon is just the beginning of the story. You have to get out there and feel the elevation change to really understand what those lines mean.

If you’re planning a trip, start by marking your "Must Sees" but then look at the topography. That’s where the real travel happens. Stop at a ranger station. Buy the paper map. Those creases in the paper are often more reliable than the blue dot on your screen when you're deep in the timber. All you've got to do is start driving and keep your eyes on the horizon, not just the GPS.