You’ve probably seen the standard green-and-brown smudge on a school wall. That’s the usual map of United States Appalachian Mountains most of us grew up with. It looks like a simple, bumpy spine running down the East Coast. But honestly? That map is lying to you—or at least, it’s leaving out the best parts.

The Appalachians aren't just one long hill. They are a massive, ancient, and incredibly messy geological puzzle that stretches all the way from the grit of Newfoundland in Canada down to the humid red clay of Alabama. If you look at a high-resolution topographic map, you’ll notice it’s not a single line. It’s a series of ridges, valleys, and plateaus that define how people live, drive, and even speak in the eastern U.S.

Why the Map of United States Appalachian Mountains is Older Than You Think

When you look at the map of United States Appalachian Mountains, you’re looking at a ghost. These peaks used to be as tall as the Himalayas. Seriously. About 300 million years ago, during the formation of the supercontinent Pangaea, Africa slammed into North America. The result was a jagged, soaring range of ice and rock.

Time is a brutal architect.

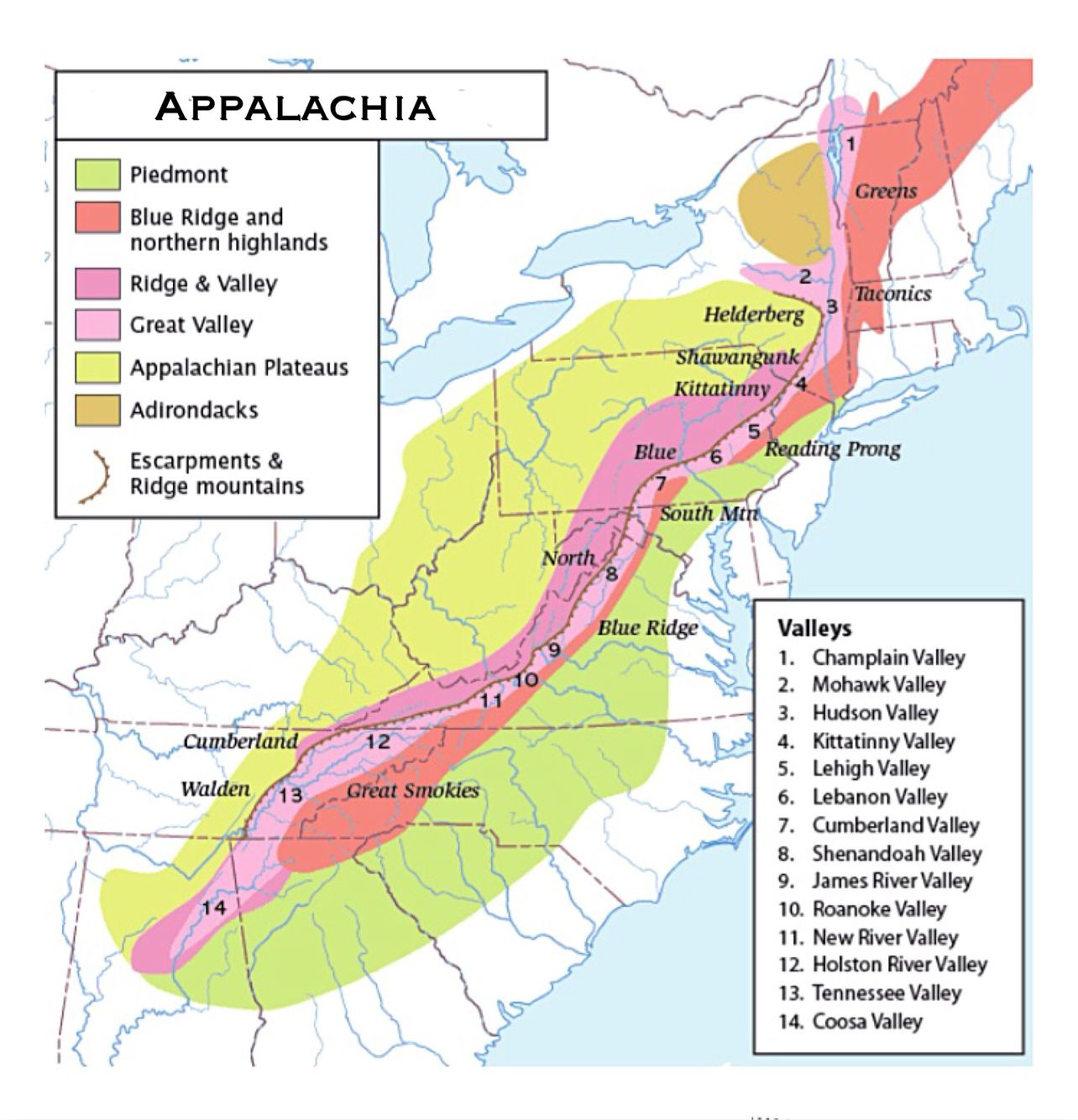

Hundreds of millions of years of rain, wind, and frost have ground those peaks down into the rolling, blue-misted ridges we see today. Geologists like those at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) categorize the range into distinct provinces. You’ve got the Piedmont, the Blue Ridge, the Ridge and Valley, and the Appalachian Plateau. Each one looks completely different on a physical map.

The Blue Ridge vs. The Alleghenies

People mix these up constantly. On a map of United States Appalachian Mountains, the Blue Ridge is that easternmost rampart. It’s where you find the highest peaks, like Mount Mitchell in North Carolina, sitting at 6,684 feet. It’s steep. It’s rugged.

Then you have the Alleghenies and the Cumberland Plateau to the west. These aren't "mountains" in the way a kid draws them. They are technically dissected plateaus. If you were a bird flying over West Virginia, it would look like a giant crumbled a piece of paper and laid it flat. The rivers have carved deep, winding gashes into the earth over eons, creating a labyrinth that makes building roads an absolute nightmare.

Navigating the Great Valley

If you trace a line on a map of United States Appalachian Mountains from Pennsylvania down through Virginia and Tennessee, you’ll see a long, relatively flat strip nestled between the high ridges. This is the Great Appalachian Valley.

👉 See also: Road Conditions I40 Tennessee: What You Need to Know Before Hitting the Asphalt

It’s been the "superhighway" of North America for thousands of years.

Indigenous peoples used it as a trade route. Later, European settlers followed the "Great Wagon Road" through this valley because, frankly, crossing the actual ridges was a great way to break a wagon wheel or lose a horse. Today, if you’re driving I-81, you’re basically following the prehistoric footsteps of mammoths and hunters who knew the geography better than we do with our GPS.

It’s not just a southern thing

Most people think of "Appalachia" and immediately picture Kentucky or West Virginia. But look at the northern end of the map of United States Appalachian Mountains. The White Mountains in New Hampshire and the Green Mountains in Vermont are part of this same family. Even the Adirondacks in New York—though geologically distinct in their rock type—are often grouped into the broader Appalachian landscape in cultural maps.

The terrain changes wildly. In the south, the forest is dense, deciduous, and humid. In the north, it turns into spruce-fir "taiga" forest that feels more like Canada or Siberia.

The Human Impact of the Terrain

Geography is destiny. Or at least, it’s a very loud suggestion.

The ruggedness shown on any map of United States Appalachian Mountains explains why the region developed such a unique culture. Isolated "hollows" (pronounced hollers if you’re from there) allowed communities to preserve music, dialects, and traditions that died out in the flatter, more connected coastal cities.

It’s hard to build a city on a 45-degree slope.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Alta West Virginia: Why This Greenbrier County Spot Keeps People Coming Back

Because of the steep V-shaped valleys in places like Eastern Kentucky and Southern West Virginia, towns are often "string towns." They are long and skinny, hugging the narrow strips of flat land alongside creeks and railroad tracks. You can see this clearly on satellite maps; the lights at night form glowing ribbons through the dark mountain masses.

The Coal and the Curves

The map also reveals why certain industries took over. The Appalachian Plateau is sitting on top of some of the richest carbon deposits on earth. The folded nature of the rock made surface mining and deep-shaft mining the economic engines of the region for a century.

But it’s a double-edged sword.

The same mountains that provided the coal also made it incredibly expensive to build diverse economies. When your "flat" land is underwater every time it rains because it’s at the bottom of a steep basin, you struggle to build factories or malls.

Real Spots to See the Map Come to Life

If you want to actually feel the map of United States Appalachian Mountains under your boots, skip the highway.

- McAfee Knob, Virginia: This is arguably the most photographed spot on the Appalachian Trail. You stand on a protruding tongue of rock looking out over the Ridge and Valley province. You can literally see the waves of the earth stretching toward the horizon.

- Clingmans Dome, Tennessee/North Carolina: It’s the highest point in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. On a clear day—though they are rare because of the "smoke" (actually VOCs from trees)—you can see seven states.

- The Delaware Water Gap: Here, the Delaware River literally cuts through a mountain ridge. It’s a massive "water gap" that shows just how powerful erosion is compared to solid stone.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Map"

There’s a common misconception that the Appalachians end at the edge of the woods.

They don't.

🔗 Read more: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

Geologically, the "Fall Line" is where the hard rock of the Appalachian foothills meets the soft sediment of the Coastal Plain. This is why cities like Washington D.C., Richmond, and Philadelphia are where they are. Early explorers could sail up rivers until they hit the first set of waterfalls caused by the Appalachian rock. They had to stop there and unload their ships.

So, in a way, the map of United States Appalachian Mountains dictated the location of the biggest cities in the U.S.

Taking Action: How to Use This Knowledge

If you're planning a trip or researching the region, don't just look at a flat paper map. Use a 3D terrain visualizer like Google Earth or a specialized topographic app like Gaia GPS.

First, look for the "gaps." Places like the Cumberland Gap were the only reason westward expansion was possible in the 1700s. Finding these notches on the map tells you where the history happened.

Second, check the elevation profiles if you're hiking or biking. A five-mile hike in the Appalachians is not the same as a five-mile hike in Florida. The "Piedmont" sections are rolling hills, but once you hit the "Escarpment," you're looking at vertical climbs that will wreck your knees if you aren't ready.

Third, pay attention to the watersheds. The Appalachians are the Great Divide of the East. Rain falling on one side of a ridge goes to the Atlantic; rain on the other side travels thousands of miles to the Gulf of Mexico via the Mississippi.

The map of United States Appalachian Mountains isn't just a drawing of some old hills. It’s a blueprint of how the continent was smashed together, how the water flows, and why the people who live there are as resilient as the rock itself. Next time you're looking at that green-and-brown smudge, remember you're looking at the worn-down teeth of a once-mighty giant.

Explore the National Park Service's digital archives for the Blue Ridge Parkway to see detailed historical maps that show how engineers actually wound roads around these peaks without tunnels. Or, better yet, grab a physical topo map of the Monongahela National Forest and try to find a cell signal. Spoilers: You won't find one, and that’s exactly the point.