You’re standing on the dock at Trenton, looking north. Ahead of you lies 386 kilometers of some of the most engineered yet wildly natural water in North America. But here’s the thing: if you just glance at a basic map of Trent Severn Waterway, you’re going to miss the reality of the "Big Chute" or why the water levels in the Kawarthas might suddenly ruin your weekend.

It's a massive system.

Owned and operated by Parks Canada, this National Historic Site isn't just a straight line from Lake Ontario to Georgian Bay. It’s a winding, complex series of 44 locks, including two of the highest hydraulic lift locks in the entire world. Most people think they can just "wing it" with a GPS. Honestly? That’s a mistake.

Why a Map of Trent Severn Waterway is More Than Just a Navigation Tool

When you first open a map of Trent Severn Waterway, it looks like a simple blue vein cutting through Ontario’s cottage country. You see names like Rice Lake, Lake Simcoe, and the Otonabee River. But a map here serves as a survival guide for your propeller.

The depth varies. Constantly.

While the guaranteed navigation depth is technically 6 feet (1.8 meters), that's often "best-case scenario" depending on the time of year and how much rain fell in the Haliburton Highlands last week. If you’re drawing 5 feet, you’re going to be sweating through some of the rock-cut channels near Port Severn.

There's a specific kind of stress that comes with watching your depth sounder scream at you while you're surrounded by granite walls. That’s why the official Small Craft Charts (specifically Charts 2021 through 2028) are the only things you should actually trust. A digital map on a phone is a "nice to have," but the paper charts show the "deadheads"—submerged logs that have been there since the logging era of the 1800s.

The Two Icons: Peterborough and Kirkfield

You can't talk about the waterway without mentioning the Peterborough Lift Lock (Lock 21). It’s a marvel. It lifts boats 19.8 meters (65 feet) using nothing but gravity and water weight. No pumps. Just pure physics.

Further along, the Kirkfield Lift Lock (Lock 36) does the same thing but in reverse depending on your direction, sitting at the highest point of the canal. This is the "summit." Once you pass Kirkfield, you’re literally going downhill toward Georgian Bay. On a map, this looks like a tiny dot. In person, it feels like you’re on a water-based elevator in the middle of a forest.

Navigating the Lakes vs. The Rivers

The waterway is basically split into three distinct "vibes." You’ve got the southern river sections, the central lakes (The Kawarthas), and the rugged northern granite.

✨ Don't miss: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

The southern end starts at Trenton. It's lush. It's agricultural. You’re following the Trent River, and it’s fairly predictable. But then you hit Rice Lake. Don't let the name fool you; it’s shallow and can get incredibly "choppy" the moment a south wind hits. Weeds are a nightmare here. If your intake isn't screened, you'll be cleaning out your raw water strainer every twenty minutes.

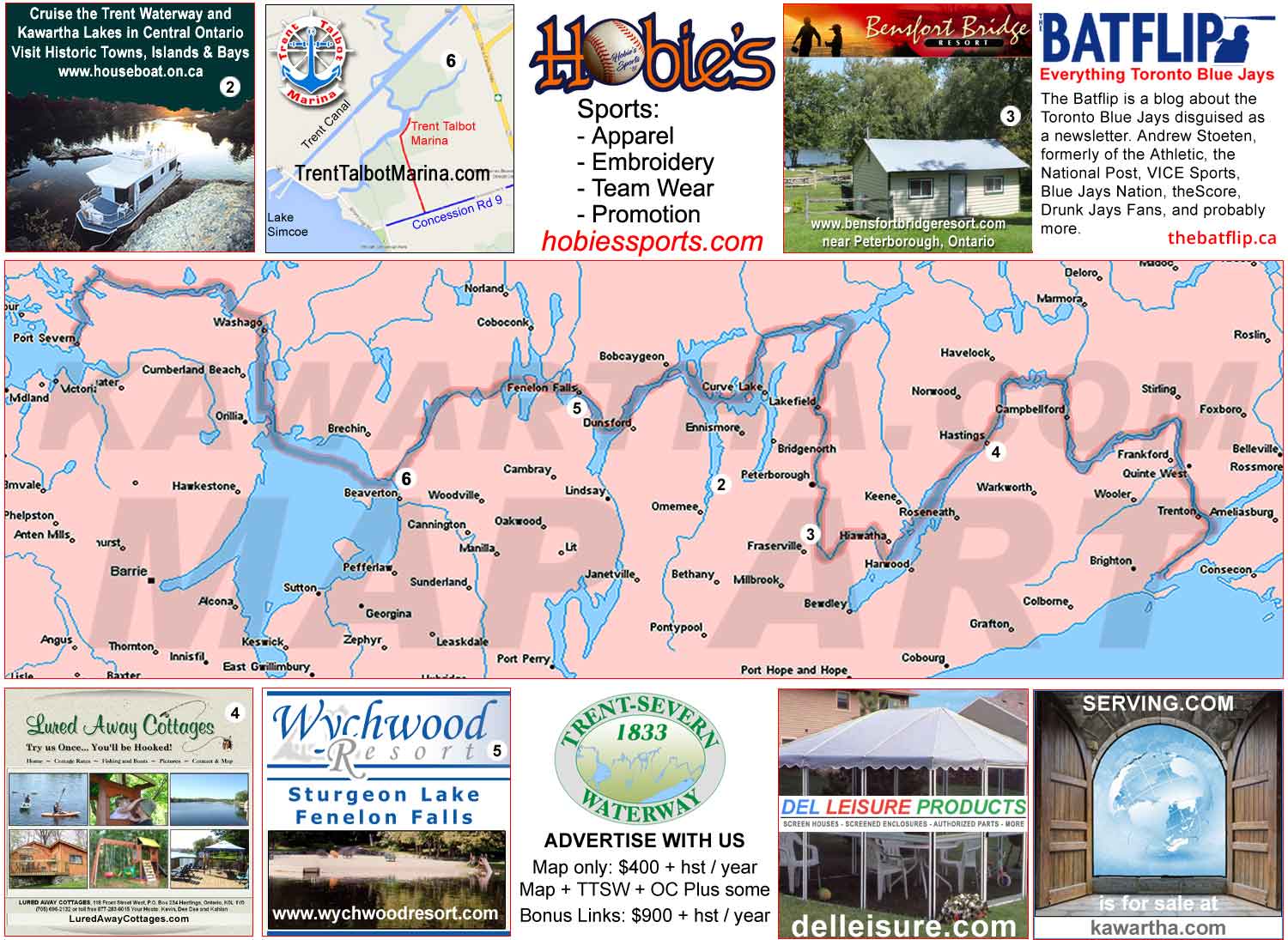

Moving into the Kawarthas—Stoney, Clear, Buckhorn, Pigeon—the scenery shifts. This is the heart of Ontario cottage culture. The map of Trent Severn Waterway gets crowded here with markers. You’ll see red and green buoys everywhere.

Expert Tip: Red, Right, Returning. But "returning" on the Trent-Severn means traveling away from the nearest Great Lake. If you’re heading toward Lake Simcoe from Trenton, you keep the red buoys on your right. If you’re heading from Simcoe toward Georgian Bay, the red buoys stay on your right again because you’ve passed the summit at Kirkfield. It’s confusing. People mess it up every year.

The Granite Trap of the Severn River

Once you cross Lake Simcoe—which is essentially a small inland sea—you enter the Severn River. This is the "Canadian Shield" portion. It is stunningly beautiful and dangerously rocky.

The Big Chute Marine Railway (Lock 44) is located here. It’s not a lock at all. It’s a massive carriage that lifts your boat out of the water, carries it over a road, and drops it back into the river. It was built because they didn't want to allow sea lampreys to migrate into the internal lakes. It’s the only one of its kind left in North America.

If your map doesn't clearly show the "Swift Rapids" section, get a better map. The current here can be surprisingly strong when the Gloucester Pool levels are being adjusted.

Practical Logistics: Bridges and Clearances

It’s not just about what’s under your boat. It’s about what’s over it.

Fixed bridges on the TSW generally have a clearance of 22 feet (6.7 meters). If you have a massive flybridge or a sailboat with a fixed mast, you aren't making it through. Period. You’ll see people at the marinas in Orillia or Bobcaygeon frantically measuring their antennas.

- Swing Bridges: These are manually or electrically operated. You wait for the light to turn green.

- Wait Times: On a long weekend in July, expect to wait. Lockmasters prioritize getting as many boats in as possible, often "rafting" boats together.

- Mooring: You can actually stay overnight at most locks for a very small fee. It’s basically the cheapest waterfront "hotel" in Canada.

The "Blue Line" Etiquette

On the map of Trent Severn Waterway, look for the designated "blue lines" at each lock station. This is where you tie up if you intend to go through the lock.

🔗 Read more: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

Don't tie up there if you just want to go get an ice cream in Fenelon Falls. That’s a fast way to get a lecture from a Parks Canada employee. The blue line is for "active" transit. If you want to stay the night, you move to the areas designated for "overnight mooring" after the lockage is done for the day.

Seasonal Realities and Water Flow

Parks Canada manages the water levels for more than just boaters. They have to balance the needs of hydro-electric plants, local residents concerned about flooding, and fish spawning.

In late August, the "feeder lakes" up north start to get low. This means the canal might see reduced depths. Conversely, in a wet June, the current in the Otonabee River can be so fast that smaller vessels struggle to make headway.

Check the "Scotsman Point" or "Gannon’s Narrows" areas on your map. These are bottleneck points where the water moves faster and the boat traffic is thick. Honestly, Gannon’s Narrows on a Saturday in August is basically a floating parking lot. Everyone is looking at their maps, no one knows quite where the channel is, and the rental pontoon boats are zig-zagging. Keep your eyes up.

Misconceptions About the TSW

A lot of people think the Trent-Severn is just for "old people in trawlers."

Actually, the demographic has shifted. You’ll see 20-foot bowriders doing the whole "Loop" (The Great Loop), and you'll see kayakers doing the "Paddle the Trent" challenge. The map doesn't show the physical toll of 40+ locks on your arms if you're in a canoe.

Another myth: "The water is always calm because it’s a canal."

Wrong. Lake Simcoe can produce 6-foot waves with very short periods. It’s shallow, so the waves "stack" up. It can be dangerous. Many boaters get trapped in Orillia or Lagoon City for days waiting for the "Simcoe crossing" to be safe. Always check the weather at Cook’s Bay and the main body of Simcoe before committing to that leg of the map.

Essential Gear for the Voyage

Beyond the physical map of Trent Severn Waterway, you need specific hardware.

💡 You might also like: Weather at Lake Charles Explained: Why It Is More Than Just Humidity

- Fenders: You need at least four large fenders. The lock walls are concrete and rough. They will chew up your gelcoat in minutes.

- Lock Lines: Have at least two 50-foot lines. You don't use your own lines to tie to the lock; you usually hold onto drop cables, but having long lines is essential for the "blue line" wait.

- A Hook: A telescoping boat hook is your best friend.

- Parks Canada Pass: You can buy a single lockage, a return trip, or a seasonal pass. If you're doing more than five locks, just get the season pass. It saves a headache.

Actionable Steps for Your First TSW Trip

If you’re planning to tackle this route, don't just print a PDF and hope for the best.

First, download the "Water Levels" app from Parks Canada. It gives real-time data on flow rates and any emergency closures. Sometimes a bridge breaks. Sometimes a lock gate needs repairs. You don't want to find that out after driving 4 hours.

Second, buy the "Trent-Severn Waterway Cruising Guide." It’s a book, often spiral-bound, that provides "strip maps." These are much easier to read while at the helm than a giant unfolding chart. It lists where the gas docks are, which marinas have mechanics, and—most importantly—where the best butter tarts are (it's Lock 27 in Young’s Point, by the way).

Third, practice your slow-speed maneuvering. Locking through requires you to hold a position in a confined space with wind and current. If you haven't mastered "back and fill" or pivoting your boat, the Trent-Severn will be a stressful experience rather than a vacation.

Finally, plan for "The Big Chute" ahead of time. If you have a deep keel or a specific hull shape, check the Parks Canada website for the dimensions of the carriage. Most recreational boats are fine, but it’s worth a 5-minute check to ensure your vessel fits the straps.

The waterway is a slow-motion adventure. You’re capped at 10km/h (about 6mph) in most of the canal portions. It’s about the journey, the history of the 1920s concrete, and the transition from the muddy south to the windswept pines of the north. Use the map to keep your prop safe, but keep your eyes on the shoreline. That's where the real magic of the Trent-Severn lives.

Reach out to local marinas like those in Peterborough or Port Carling if you’re unsure about current draught conditions. They live on this water and know the "unofficial" depth of the channels better than any government-issued map ever could.

Check the Parks Canada "Notice to Shipping" page before you untie your lines. It’s the most up-to-date resource for temporary hazards, bridge malfunctions, or changed operating hours that could impact your transit through the system.