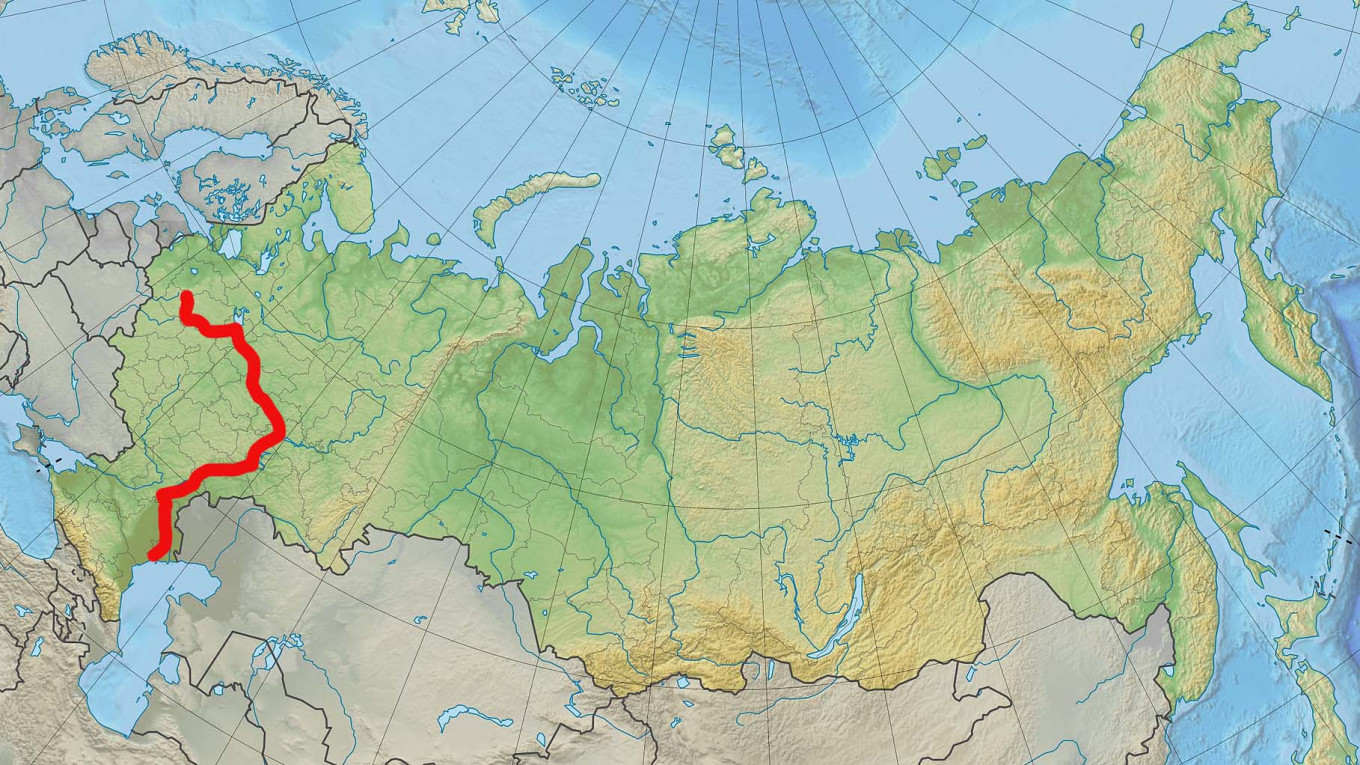

You look at a map of the Volga River in Russia and honestly, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by the sheer scale of the thing. It isn’t just a squiggle on a page. It’s a massive, 2,200-mile artery that basically functions as the circulatory system for European Russia. If you traced it with your finger, you’d be tracing the history of an entire empire.

It starts small. Tiny, really.

Up in the Valdai Hills, about halfway between Moscow and Saint Petersburg, the Volga begins as a humble spring. You could probably jump across it without breaking a sweat. But by the time it reaches the Caspian Sea? It’s a monster. It drains an area roughly the size of one-third of European Russia. People call it "Mother Volga" (Volga-Matushka) for a reason. It isn’t just geography; it's an identity.

Where Exactly Does the Volga Go?

If you’re staring at a map of the Volga River in Russia, you'll see it makes a giant, lazy "S" shape across the landscape. It heads east toward the Ural Mountains before deciding, "Nah, not today," and hanging a sharp right to head south.

The river hits some of the most famous cities in the country. You’ve got Tver, Yaroslavl, and Nizhny Novgorod. Then it flows down to Kazan—where the minarets of the Kremlin reflect in the water—and continues through Samara and Volgograd. Finally, it splits into a massive delta near Astrakhan.

The delta is wild. It has over 500 channels. If you get lost there, you're staying lost for a while. It’s one of the few places in Russia where you’ll find lotus flowers blooming in the wild, which feels kinda weird considering you're in the middle of a Russian steppe.

The Upper Volga: Forests and Ancient Spires

The top part of the map is all about old-world Russia. This is the region of the "Golden Ring." Towns like Uglich and Kostroma sit right on the banks. If you were traveling here in the 1800s, you’d see burlaki—barge haulers—straining against thick ropes to pull boats upstream. It was brutal work. Ilya Repin’s famous painting Barge Haulers on the Volga captured this perfectly.

Today, it's quieter. Mostly.

💡 You might also like: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

The flow is heavily regulated now. You won’t see many "natural" banks in the upper stretches because of the "Greater Volga" project. This was a massive Soviet-era undertaking to turn the river into a series of giant reservoirs. They basically turned the river into a staircase of lakes.

- Ivankovo Reservoir: Often called the "Moscow Sea."

- Rybinsk Reservoir: At the time it was built, it was the largest man-made body of water on Earth.

When they filled the Rybinsk, they drowned entire towns. The bell tower of St. Nicholas Cathedral in Kalyazin still pokes out of the water like a ghost. It’s a haunting sight that most maps don't really prepare you for.

Navigating the Middle and Lower Volga

Once the river passes Nizhny Novgorod, it meets the Oka River. This is a big deal. The volume of water almost doubles.

Then comes Kazan. This is where the map of the Volga River in Russia gets culturally interesting. You’re moving from the Slavic heartland into Tatarstan. The river here is wide—sometimes so wide you can’t see the other side clearly.

The Zhiguli Mountains Bend

Near Samara, the river does something strange. It hits the Zhiguli Mountains and has to loop around them. This is known as the Samara Bend (Samarskaya Luka). It’s a national park now. The cliffs are limestone and drop straight into the water. It’s gorgeous.

In the old days, pirates used to hide in these cliffs. They’d wait for merchant ships loaded with Persian silk or salt to come around the bend and then pounce. Legend says the famous rebel Stenka Razin had a secret cave here.

- Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad): This is the southernmost major bend. The river here is massive, nearly 2 miles wide in places.

- The Volga-Don Canal: This is a crucial "junction" on your map. It links the Volga to the Don River, which flows into the Sea of Azov and then the Black Sea. This effectively connects the Caspian to the World Ocean.

- The Delta: South of Astrakhan, the river gives up its singular identity. It dissolves.

Why the Map Looks Different Than it Used To

If you found a map from 1920 and compared it to one from 2026, you’d think you were looking at two different planets.

📖 Related: Atlantic Puffin Fratercula Arctica: Why These Clown-Faced Birds Are Way Tougher Than They Look

The Soviets were obsessed with "taming" nature. They built nine massive hydroelectric dams. This changed everything. The Volga isn't really a "free-flowing" river anymore; it’s more like a managed plumbing system.

The Pros: It generates a staggering amount of electricity. It allows huge cargo ships to travel from the white sea in the north all the way to the warm waters of the south. It provides irrigation for the dry steppes.

The Cons: It’s an ecological mess. The dams blocked the migration paths of the Beluga sturgeon. You know, the fish that gives us that incredibly expensive caviar? Yeah, those guys. Their numbers tanked because they couldn't get upstream to spawn.

Also, the water moves slower now. Slower water means more pollution stays put. It’s a trade-off. Modern environmentalists in Russia are constantly debating how to "fix" the Volga, but you can’t exactly just delete a dam that powers a city of a million people.

A Quick Note on the "Five Seas"

You might hear Russians talk about Moscow being a "Port of Five Seas."

Look at the map of the Volga River in Russia and its connecting canals. Through the Volga-Baltic Waterway and the Volga-Don Canal, boats can get from Moscow to the Baltic Sea, the White Sea, the Caspian Sea, the Sea of Azov, and the Black Sea. It’s a logistical miracle, even if it took a lot of forced labor and environmental shifting to get there.

The Best Ways to Actually See the River

Seeing it on a screen is fine, but being on it is different.

👉 See also: Madison WI to Denver: How to Actually Pull Off the Trip Without Losing Your Mind

River cruises are the standard way to do it. Most people go from Moscow to Saint Petersburg, but the "Long Volga" route from Moscow down to Astrakhan is the real deal. You watch the landscape change from deep, dark forests to rolling hills, then to sun-baked grasslands, and finally to the semi-desert near the Caspian.

If you're more of a DIY traveler, the "M5" and "P228" highways shadow the river for long stretches.

But honestly? Just find a high point.

In Nizhny Novgorod, there’s a massive staircase—the Chkalov Stairs—that leads down to the embankment. Sitting there at sunset, watching the sun dip below the horizon where the Volga meets the Oka, you realize the river is moving billions of gallons of water every second. It makes you feel tiny. In a good way.

Understanding the Map's Limits

Maps are just approximations.

They don't show you the smell of the pine needles in the north or the taste of the smoked catfish (som) sold at roadside stands in the south. They don't show the "Green Stops" where cruise ships let people off to swim in the surprisingly warm (and occasionally tea-colored) water.

They also don't show the seasonal changes. In winter, a map of the Volga River in Russia is basically a map of a giant ice highway. The river freezes solid for months. People drive cars on it. They drill holes and fish through the ice. Then, in the spring, the "ice run" happens. The sound of giant sheets of ice crashing against each other is like thunder. It’s terrifying and beautiful.

Practical Steps for Your Journey

If you’re planning to use a map to navigate or explore the Volga, keep these things in mind to make the most of it:

- Check the Water Levels: If you're renting a small boat, remember that late summer can see lower levels in certain branches of the delta, while spring floods can make the current deceptively strong.

- Focus on the "Bend" Cities: For the best photography and history, prioritize Samara and Volgograd. The elevation changes there give you the best "map-like" views from the ground.

- Use Digital Topo Maps: For the Valdai Hills (the source), standard Google Maps won't cut it. You want topographic maps like those from the Russian Federal Agency for Geodesy to find the actual marshy start of the river.

- Download Offline Layers: Data signal is great in Kazan or Samara, but when you're cruising through the vast stretches between Saratov and Astrakhan, your GPS will fail you without pre-loaded maps.

- Identify the Locks: If you’re on a boat, mark the lock systems (like at Tolyatti). Waiting for the water levels to shift in a massive concrete chamber is a bucket-list experience for any geography nerd.

The Volga isn't just water. It's a 3,500-kilometer story. Once you understand the map, you start to understand why Russia is the way it is. It's all tied to this one, long, winding, dammed-up, beautiful mess of a river.