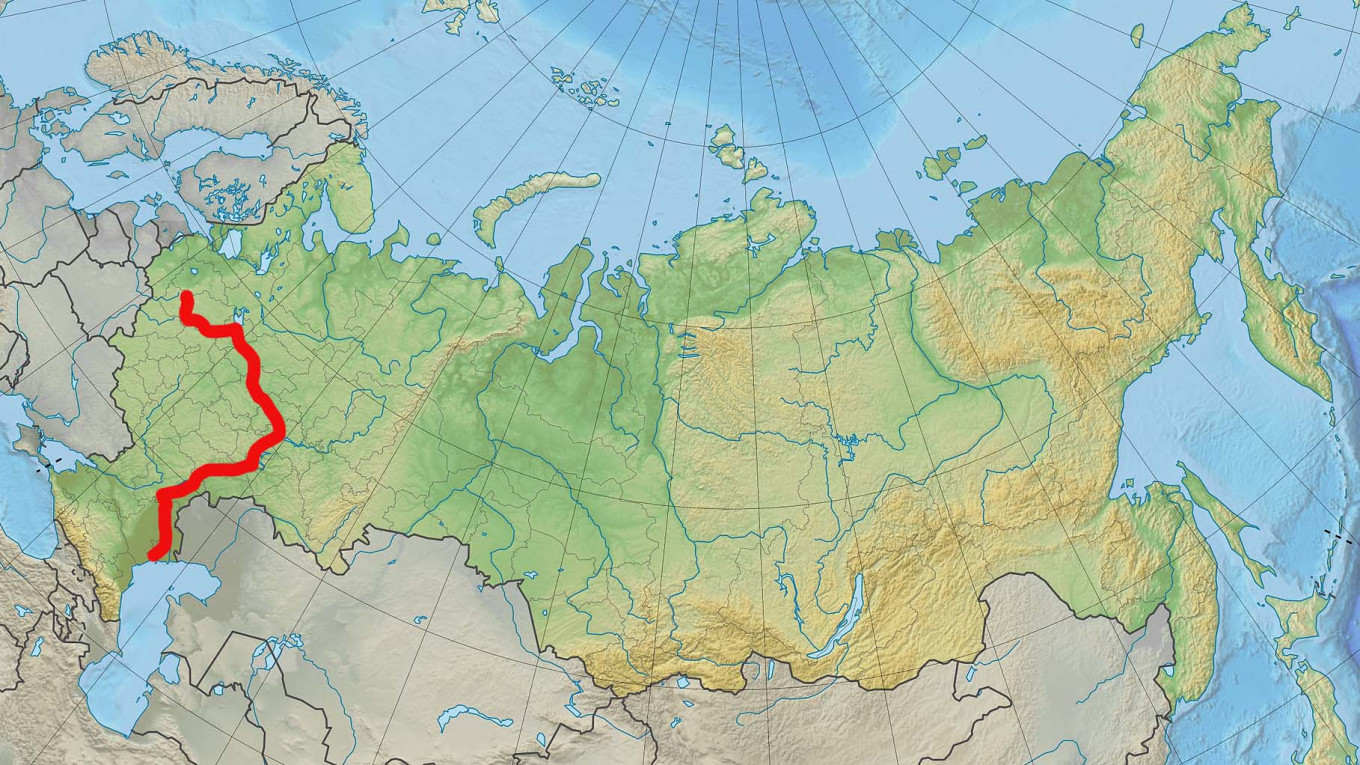

If you look at a map of the Volga River, you aren't just looking at a blue line snaking through a continent. You're looking at the actual spine of a nation. It’s huge. Honestly, the scale is hard to wrap your head around until you realize this single river basin covers about one-third of European Russia. People call it "Mother Volga" for a reason. It’s not just sentiment; it’s geography.

The river starts in the Valdai Hills, northwest of Moscow, at an elevation of only about 225 meters. That’s basically a tall hill. From there, it drifts, winds, and eventually pours into the Caspian Sea some 3,530 kilometers later. Because the drop in elevation is so gradual, the water moves slow. It’s a lazy, massive giant.

Most people expect a mountain-fed torrent. It isn’t that. It’s a series of massive reservoirs held back by some of the most impressive (and controversial) dam engineering projects of the 20th century. If you’re trying to navigate it or just understand the layout, you have to look at it in three distinct chunks: the Upper, Middle, and Lower Volga. Each one feels like a different country.

Why the Upper Volga Map Looks Like a Chain of Lakes

When you trace the map of the Volga River near its source, you'll notice it doesn't look much like a river at all for the first few hundred miles. It looks like a string of pearls, or more accurately, a sequence of flooded valleys. This is the "Upper Volga." It runs from the source down to the confluence with the Oka River at Nizhny Novgorod.

In the old days, this part of the river was shallow and tricky. Now? It’s a massive industrial and transport artery. You’ve got the Rybinsk Reservoir, which, when it was created in the 1940s, was the largest man-made body of water on earth. It literally swallowed the historic town of Mologa. Divers still go down there to see the ruins. It’s eerie.

The Upper Volga is where you find the "Golden Ring" cities. Yaroslavl and Kostroma sit right on the banks. If you're looking at a map for travel purposes, this is the cruise capital. The river here is wide, calm, and flanked by birch forests that look exactly like a Levitan painting.

The Moscow Connection

One thing the map doesn't always show clearly is that Moscow isn't actually on the Volga. It’s on the Moskva River. But, thanks to the Moscow Canal, the city is technically a "port of five seas." The canal links the Volga to the capital, allowing massive ships to sail from the Caspian all the way to the heart of the Kremlin. It’s a 128-kilometer feat of engineering that changed the geography of the region forever.

The Middle Volga: Where East Meets West

Once you hit Nizhny Novgorod, everything changes. The Oka River joins in, and the Volga suddenly doubles in size. This is the Middle Volga. It’s the cultural fault line of Russia.

👉 See also: Weather in Kirkwood Missouri Explained (Simply)

Look at the map of the Volga River between Nizhny and Samara. You’ll see the river take a hard turn south. This is where the forest gives way to the steppe. It’s also where the ethnic and religious map gets interesting. You pass through Tatarstan and Chuvashia.

Kazan is the crown jewel here.

In Kazan, the skyline has both minarets and Orthodox domes. The river is so wide here—at the Kuybyshev Reservoir—that you often can't see the other side. It’s more like an inland sea. This reservoir is actually the largest in Europe by surface area. It’s so big that it has its own weather patterns and can produce waves significant enough to toss smaller boats around.

The "Zhiguli Bend" near Samara is another weird geographic quirk. The river hits the Zhiguli Mountains and is forced into a massive 180-degree loop. It’s one of the most beautiful spots on the entire map, full of limestone cliffs and thick forests that stand in stark contrast to the flat plains nearby.

The Lower Volga and the Dying Delta

South of Saratov, the river enters its final act. This is the Lower Volga. The climate gets dry. Deserts start to creep in from the east. By the time you reach Volgograd (formerly Stalingrad), the river is a beast.

But then, something strange happens on the map.

Just south of Volgograd, the Volga-Don Canal connects the Volga to the Don River, which flows into the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. This is the vital link for global shipping. If you’re a cargo captain, this is the most important "turn" on your entire route.

✨ Don't miss: Weather in Fairbanks Alaska: What Most People Get Wrong

Finally, the river reaches the Caspian Depression. It’s below sea level here. The river breaks apart into over 500 smaller channels and streams, forming the Volga Delta.

- Size: The delta is about 160 kilometers wide.

- Wildlife: It’s a UNESCO-protected site because of the lotus fields and the sturgeon.

- The End: The water doesn't "exit" into an ocean; it pours into the landlocked Caspian Sea.

The Delta is a maze. If you’re looking at a map of the Volga River to go fishing or bird watching, this is where you end up. It’s the only place in Russia where you can find wild pelicans and flamingos. It’s also the home of the famous Beluga sturgeon, though they’re much rarer now than they were fifty years ago due to the dams upstream blocking their spawning routes.

The Engineering Reality Most Maps Ignore

We talk about the river like it’s a natural thing. It’s really not anymore. The Volga is a "managed waterway."

There are nine major hydroelectric dams. They provide a massive amount of power, but they've basically turned the river into a series of stagnant ponds. This is a huge environmental issue. The water doesn't flow fast enough to clean itself anymore. Blue-green algae blooms are a nightmare in the summer, especially near Samara and Tolyatti.

The dams also stopped the silt. Usually, a river carries sediment to its delta to keep it healthy. Because of the dams, the Volga Delta is actually shrinking and changing shape in ways that aren't reflected on older maps.

Logistics and the Modern "Viking" Route

If you’re using a map to plan a trip, remember that the Volga is frozen for a good chunk of the year. In the north, it’s closed from late November to April. Down south near Astrakhan, the ice might only hold for a few weeks, or not at all in a warm year.

The "Volga-Baltic Waterway" is the modern version of the old Viking trade routes. You can literally take a boat from the Caspian Sea, go up the Volga, through a series of canals and lakes (like Onega and Ladoga), and pop out in the Baltic Sea at Saint Petersburg. It’s one of the most important logistical corridors in the world, moving millions of tons of oil, timber, and grain every year.

🔗 Read more: Weather for Falmouth Kentucky: What Most People Get Wrong

Practical Steps for Exploring the Volga

If you’re actually planning to use a map of the Volga River to see the region, don't try to do the whole thing in one go unless you have three weeks to spare. It's too big.

Pick a specific segment based on your interest:

For history and classic Russian architecture, focus on the Upper Volga between Tver and Kostroma. This is where you'll find the wooden churches and the quiet, "old Russia" vibe.

For food and cultural blending, go to the Middle Volga. Spend time in Kazan. The mix of Tatar and Russian culture is something you won't find anywhere else, and the riverfront there is world-class.

For nature and "roughing it," hit the Delta. Fly into Astrakhan. Rent a boat with a local guide. You cannot navigate the Delta alone; the map changes every season as channels silt up and new ones open.

Check the water levels:

If you're boating, be aware that late summer can see lower water levels in certain reservoirs, affecting navigation for deeper-draft vessels. Always consult the latest "pilot charts" which are much more detailed than a standard topographical map.

Respect the scale:

Everything on the Volga takes longer than you think. A "short" boat hop between cities can take ten hours. The distances are deceptive because the river is so wide it feels like you're moving slowly, even when you're at full throttle.

To get the most out of your research, start by overlaying a topographical map with a modern satellite view. You'll see the sheer impact of the reservoirs and how the "original" riverbed is often miles away from the current shoreline. Understanding that tension between the natural river and the engineered one is the key to truly reading the Volga.