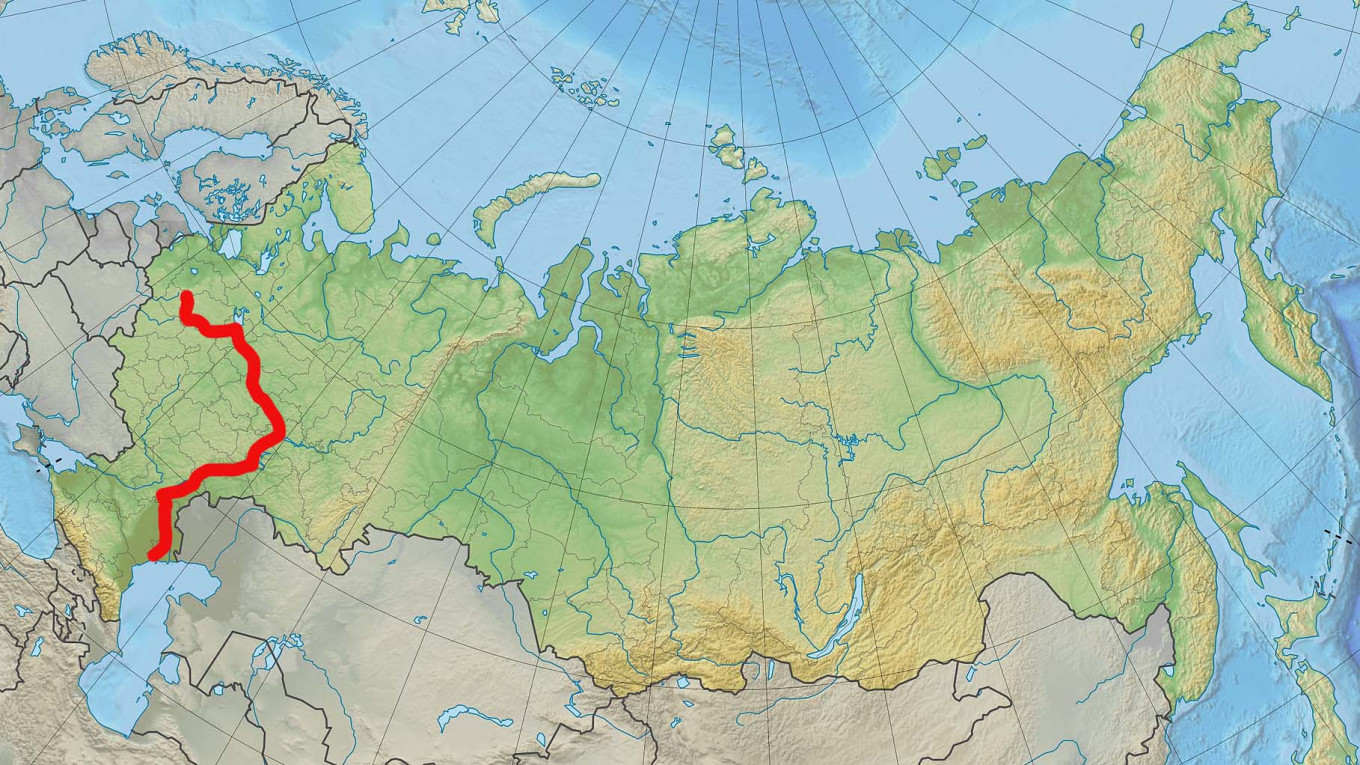

You can't really understand Russia by looking at Moscow. Honestly, if you want to see the nervous system of the country, you have to look at a map of the Volga. It’s massive. It’s messy. It’s basically a 2,300-mile long liquid highway that somehow manages to touch almost every defining moment of Eastern European history.

People call it "Mother Volga" for a reason. But when you pull up a digital map or crack open an old atlas, what you're seeing isn't just water. You're looking at a series of massive, man-made "seas" created by Soviet engineering, ancient Silk Road trade nodes, and a drainage basin that’s home to roughly 60 million people. That is nearly half of Russia’s entire population living in one river valley. Think about that for a second.

Why Your Map of the Volga Looks Different Today

If you found a map of the Volga from the year 1900 and compared it to a Google Maps view today, you might think you were looking at two different planets. Before the 1930s, the Volga was a "natural" river. It had shallows. It had rapids. In the summer, it would get so low in places that large boats couldn't pass.

Then came the Great Volga Scheme.

The Soviet Union decided they needed electricity and reliable shipping more than they needed the original riverbanks. They built a "cascade" of dams. Today, the Volga is basically a staircase of reservoirs. Places like the Rybinsk Reservoir were so huge when they were filled that they actually changed the local climate, making the surrounding areas a few degrees cooler in the summer.

When you look at the map now, you’ll see these massive bulges in the blue line. Those aren't natural lakes. They are flooded valleys. Underneath those waters—specifically near Uglich and Mologa—entire cities, hundreds of villages, and dozens of monasteries were submerged. If you go to Kalyazin, you can see the "Flooded Belfry" of St. Nicholas Church sticking out of the water. It’s a haunting landmark that reminds you the map hides as much as it shows.

💡 You might also like: Tiempo en East Hampton NY: What the Forecast Won't Tell You About Your Trip

The Delta: Where the Map Dissolves

Down south, near Astrakhan, the river doesn't just end. It shatters. The Volga Delta is the largest inland delta in Europe. If you're looking at a high-resolution map of this area, it looks like a frayed piece of rope. There are over 500 separate channels and tiny streams.

This is where the geography gets tricky. The Caspian Sea—where the Volga empties—is a closed basin. It’s not connected to the world’s oceans. Because of this, the sea level fluctuates wildly based on how much the Volga flows. In the 1970s, the sea was shrinking, and maps had to be redrawn every few years. Then it started rising again. It’s a living, breathing landscape.

It’s also the only place in Russia where you’ll find wild lotuses. Imagine that: a Russian river ending in a field of tropical-looking pink flowers. It’s a weird, beautiful quirk of the map that most people miss because they stop looking once they see the big cities.

Key Waypoints on the Modern Map of the Volga

You can’t talk about this river without mentioning the heavy hitters. These are the anchors of any decent map.

- Nizhny Novgorod: This is where the Volga meets the Oka. It was the "wallet of Russia" because of its massive trade fairs.

- Kazan: This is a fascinating spot on the map. It’s where the river turns south. It’s also the cultural heart of Tatarstan. On one side of the river, you have the Kremlin with its cathedrals; on the other, the minarets of mosques.

- Samara: Look for the "Samara Bend" or Samarskaya Luka. The river hits the Zhiguli Mountains and has to take a massive detour, looping around in a nearly 180-degree turn. It’s a hiker's paradise and one of the most scenic spots on the entire map.

- Volgograd: Formerly Stalingrad. The river here is wide, cold, and heavy with history.

The Infrastructure Nobody Notices

Look closely at the area between the Volga and the Don. You’ll see a tiny thin line. That’s the Volga-Don Canal. Without that 63-mile stretch of dirt and concrete, the Volga would be a dead end. Because of that canal, ships can go from the Caspian all the way to the Black Sea, and eventually the Mediterranean.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Lake Placid Town Map Doesn’t Tell You

This is why Moscow calls itself the "Port of the Five Seas." Even though Moscow is hundreds of miles from any ocean, the map shows a network of canals and rivers—starting with the Volga—that connects it to the White, Baltic, Caspian, Azov, and Black Seas.

The Economic Reality of the Map

We tend to think of maps as static things, but the map of the Volga is an economic engine. It’s not just about cruise ships (though the Moscow-to-Astrakhan route is a classic). It’s about oil. It’s about caviar (though that’s getting rarer). It’s about the massive hydroelectric plants like the one at Zhigulyovskaya.

The river carries roughly half of all Russian inland freight. If the Volga stops, Russia stops. But this comes at a cost. The "cascade" of dams means the water moves very slowly. In some reservoirs, it takes over a year for a single drop of water to travel from the top to the bottom. This leads to massive algae blooms in the summer, which you can actually see on satellite maps as bright green swirls.

Mapping the Environmental Shifts

Ecologists use a different kind of map for the Volga. They look at pollution gradients and sturgeon migration routes. The sturgeon—the fish that gave the world Beluga caviar—is basically extinct in the wild Volga. Why? Because the dams blocked their path to spawning grounds.

There are projects now to "map" the restoration of the river. Scientists are looking at how to bypass dams or create artificial spawning beds. It's a race against time. The river that built the country is struggling under the weight of that same country’s industrial needs.

👉 See also: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

How to Use a Map of the Volga for Travel

If you’re actually planning to see this thing in person, don't just stick to the cruise routes. Everyone does that.

Instead, look at the map for the "Golden Ring" intersections. Yaroslavl and Kostroma are stunning. But also look for the smaller dots. Ples is a tiny town that became famous because the painter Isaac Levitan obsessed over it. It’s basically a living 19th-century landscape painting.

Then there’s the Zhiguli Nature Reserve. Most maps show it as a green blob inside the Samara Bend. It’s one of the few places where the pre-industrial landscape of the Volga still feels real.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Explorer

- Check the "Water Level" Maps: If you are renting a boat or fishing, use resources like the Federal Agency for Water Resources. They provide real-time data on reservoir levels. This is crucial because the "shoreline" on your paper map might be a mudflat if the dams are holding back water.

- Layers Matter: When using digital maps, toggle to the "Terrain" or "Satellite" view around Samara. The elevation changes are what make the river interesting. The flat steppe of the south is a completely different world from the forested north.

- Historical Overlays: Try to find a map that shows the "Old Volga" channel beneath the reservoirs. It helps you understand why certain towns are where they are—they used to be on high ground that is now a shoreline.

- The Logistic Link: Use the map to trace the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC). This is a massive project linking India to Europe via the Volga. It’s why the river is seeing a massive uptick in commercial traffic lately.

The Volga isn't just a line on a page. It's a series of trade-offs between nature and progress, history and the future. When you look at the map, you aren't just seeing geography; you're seeing the blueprint of a civilization. Stop looking at it as a way to get from point A to point B. Start looking at the bends, the flooded towns, and the frayed delta. That’s where the real story lives.

To get the most out of your study of the Volga, begin by comparing the Kuybyshev Reservoir—the largest in Europe by surface area—to the original river width near Samara. This specific geographic tension reveals the sheer scale of the 20th-century transformation. From there, trace the river's path through the Caspian Depression, the only part of Europe that sits below sea level. Understanding this drop in elevation is the key to grasping why the Volga’s flow is so unique.