You look at a standard map of the United States Appalachian Mountains and you see a green smudge. Maybe some ripples. It looks like a spine, right? A long, bumpy vertebrae stretching from the deep woods of Maine all the way down to the red clay of Alabama. But honestly, most digital maps do a terrible job of showing what’s actually happening on the ground. They make it look like one continuous pile of dirt.

It isn't.

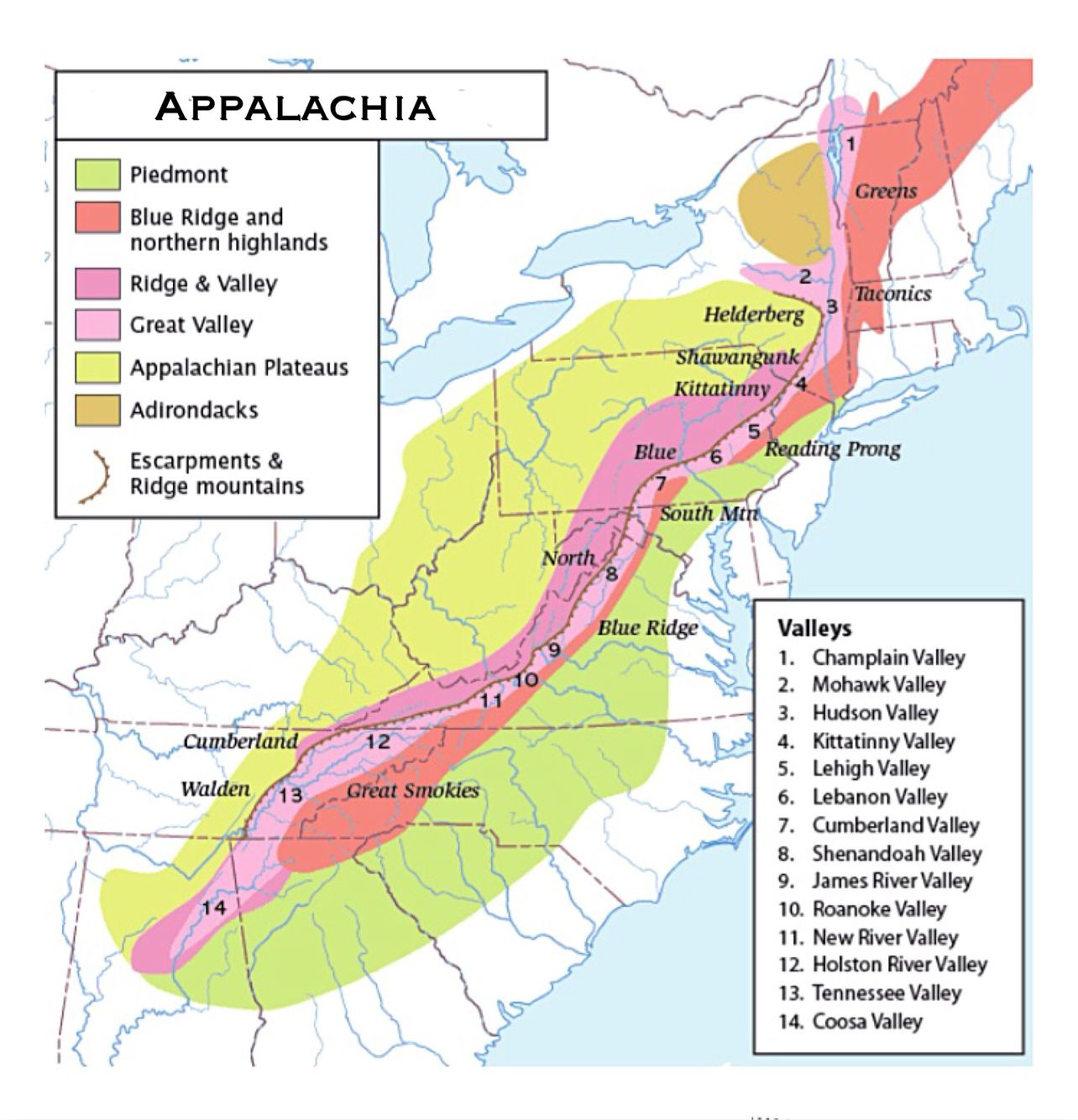

The Appalachians are a messy, ancient collection of distinct provinces. If you’re planning a road trip or trying to understand why certain towns in West Virginia are so isolated, the map is your first clue. Geologically, these mountains are older than bones. They’ve been eroding for hundreds of millions of years. What we see today is just the weathered remains of peaks that once rivaled the Himalayas. Think about that for a second. You’re walking on the stumps of giants.

The Geography Most People Miss

When you pull up a map of the United States Appalachian Mountains, your eyes probably jump to the Blue Ridge. That makes sense. It’s the iconic part. It's the Skyline Drive and the Blue Ridge Parkway. But look closer at the western edge. You'll see the Ridge-and-Valley province. This area looks like a giant piece of corrugated cardboard. Long, skinny ridges separated by flat, fertile valleys. If you’re driving across it, you’re constantly going up-down, up-down, like a literal roller coaster.

Then there’s the Allegheny Plateau. This is the "back" of the mountains. It’s not really a mountain range in the traditional sense; it’s a massive highland that’s been carved up by rivers. To someone standing in a deep holler in Kentucky, it feels like a mountain. To a geologist, it’s a dissected plateau.

Geography dictates destiny here.

The way the mountains fold determines where the roads go. It’s why you can’t get from Point A to Point B in a straight line in eastern Tennessee. The map shows you the obstacles, but it doesn't show the culture built into those folds. The isolation provided by these ridges is exactly why distinct dialects and musical traditions survived so long in places like Madison County, North Carolina.

The Great Valley: The Hidden Highway

Running right through the middle is the Great Valley. On a map of the United States Appalachian Mountains, it’s that long, pale streak. It has different names depending on where you are—the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia, the Cumberland Valley in Pennsylvania. It’s been the main north-south "highway" for thousands of years, first for bison, then for Native American trails (like the Great Indian Warpath), and eventually for the Scotch-Irish settlers moving south.

💡 You might also like: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

If you’re traveling, don’t just stay on the Interstate. I-81 follows this valley. It’s fast, sure. But it’s also packed with trucks. Move one ridge over to the east or west. That’s where the real Appalachia is.

Reading the Map of the United States Appalachian Mountains Like a Pro

Most people look for green. On a digital map, green usually means National Forest or National Park. In the Appalachians, that’s your playground. You’ve got the Monongahela in West Virginia, the George Washington and Jefferson National Forests in Virginia, and the massive Great Smoky Mountains on the border of Tennessee and North Carolina.

But here is a pro tip: check the "Relief" or "Terrain" layer.

Notice how the mountains just... stop?

In the south, there's a very sharp line called the Fall Line. It’s where the hard rock of the mountains hits the soft sediment of the coastal plain. It’s the reason so many major cities—Richmond, Raleigh, Columbia—are located exactly where they are. That’s where the waterfalls are. That’s where the boats had to stop. The map of the United States Appalachian Mountains isn’t just a guide for hikers; it’s a blueprint for why America looks the way it does.

The Highest Peaks are Hiding

You might think the tallest mountains are in the north because they’re "rugged." Nope. The highest point in the entire range is Mount Mitchell in North Carolina. It’s 6,684 feet. Compare that to Mount Washington in New Hampshire at 6,288 feet.

The southern Appalachians are actually higher and more biodiverse.

📖 Related: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

During the last Ice Age, the glaciers stopped in Pennsylvania. They never made it south. This turned the southern mountains into a "refugium"—a safe haven for plants and animals. That’s why the Smokies have more tree species than all of Europe. When you’re looking at the map, remember that the "bottom" part of the range is actually the most complex ecosystem on the continent.

Navigating the Appalachian Trail

We can’t talk about the map of the United States Appalachian Mountains without mentioning the "A.T." This white-blazed trail is a thin thread that ties the whole map together. It starts at Springer Mountain, Georgia, and ends at Mount Katahdin, Maine.

- The Southern Start: Georgia and North Carolina offer massive elevation changes.

- The Mid-Atlantic Flat(ish): Pennsylvania is famously called "Rocksylvania." The map looks flat, but the ground is covered in ankle-breaking scree.

- The Northern Finish: New Hampshire and Maine are the "Whites" and the "Wilds."

The Appalachian Trail Conservancy (ATC) provides specialized maps that are way better than Google Maps for this. They show water sources, shelters, and—most importantly—elevation profiles. Because on a 2D map, a 5-mile walk looks easy. On a 3D topo map, you realize those 5 miles include a 3,000-foot climb.

Beyond the Green: The Human Map

Appalachia isn't just a physical place; it's a defined region. The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) defines it as 423 counties across 13 states. This map is different. It includes parts of Mississippi and New York.

It’s a map of economics and culture.

Historically, this area was defined by coal, timber, and salt. If you look at a map of the United States Appalachian Mountains overlaid with resource data, you see why certain areas boomed and then crashed. The "Coal Fields" of West Virginia and Eastern Kentucky are physically distinct—narrower valleys, steeper hills, fewer ways out.

Actionable Tips for Your Next Trip

If you’re using a map of the United States Appalachian Mountains to plan a visit, do these three things to avoid getting stuck or disappointed:

👉 See also: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

Download Offline Maps.

Cell service is a joke in the high ridges. You will lose GPS signal in the middle of the Monongahela National Forest. If you don't have an offline map or a paper one, you are going to have a very long, very stressful night.

Watch the "Gap" Towns.

Look for towns with "Gap" in the name—Cumberland Gap, Delaware Water Gap. These are the natural notches in the mountain walls. They are almost always the most scenic places to cross, and they usually have the most interesting history because everyone had to pass through them.

Check the "Blue Ridge Parkway" specifically.

This isn't a normal road. It’s a 469-mile linear park. There are no gas stations on the road itself. You have to exit into local towns. Use your map to scout these exits ahead of time. Some exits lead to thriving mountain towns like Asheville; others lead to three houses and a closed general store.

The Appalachians aren't just a barrier. They are a destination that requires a bit of study. Stop looking at the map as a way to get around the mountains and start looking at it as a way to get into them. The best spots aren't on the Interstate. They’re tucked into those tiny contour lines where the road turns into a squiggle and the cell service bars disappear.

Pack a physical map. Buy a gazetteer for the state you're visiting. Trust the paper more than the screen. The mountains have a way of making tech feel very small.

Next Steps for Your Journey

- Order a USGS Topographic Map: If you're heading into the backcountry, go to the USGS Store and find the 7.5-minute quadrangle map for your specific destination.

- Study the "Physiographic Provinces": Look up the difference between the Blue Ridge and the Ridge-and-Valley to understand why the scenery changes so drastically as you drive west.

- Identify Your Access Points: Use the National Park Service maps for the Blue Ridge Parkway or the Smokies to locate "low-traffic" trailheads away from the main tourist hubs.