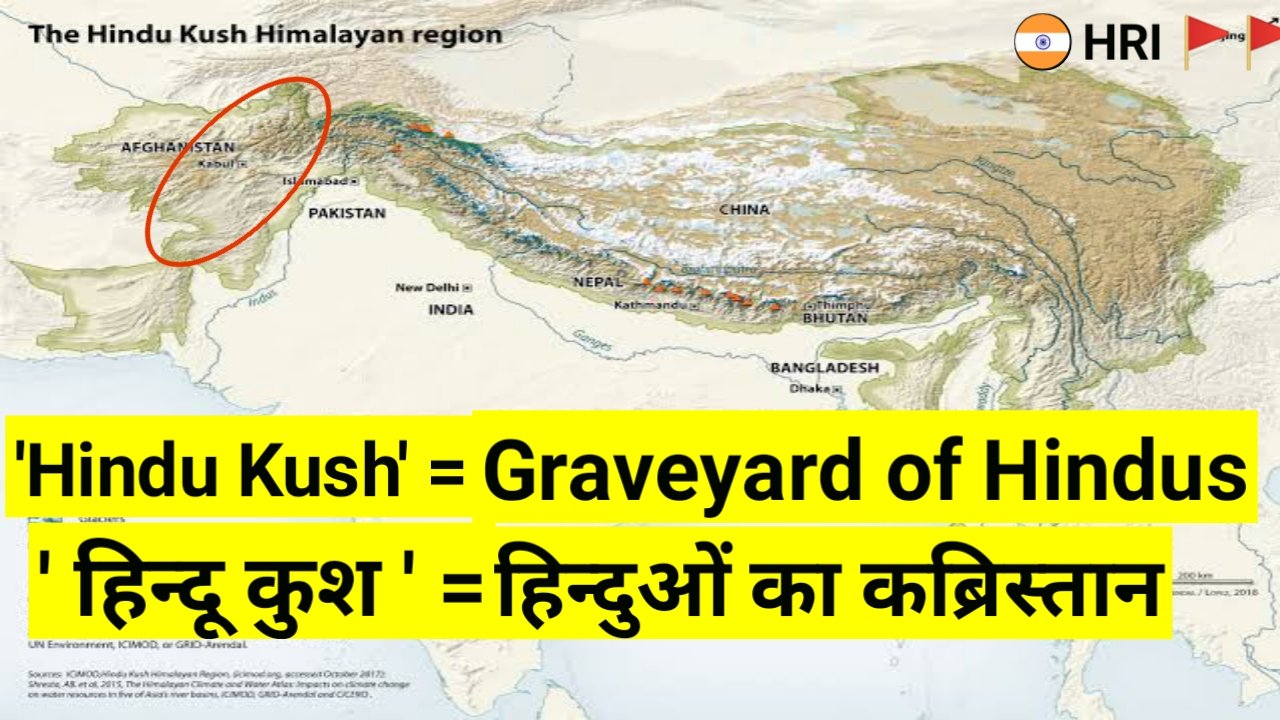

You look at a map of the Hindu Kush mountains and it just seems like a messy brown smudge across Central and South Asia. Honestly, it’s intimidating. These aren't just hills. We are talking about an 800-kilometer stretch of jagged, unforgiving rock that separates the Indus Valley from the Oxus. It is a literal wall. If you’ve ever tried to trace the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, you know the map gets chaotic fast.

The Hindu Kush is basically the "Great Wall" of nature. It’s the western extension of the Pamir Knot. People often confuse it with the Himalayas, but the vibe here is different. It’s drier. Crueler. While the Himalayas feel like a spiritual sanctuary, the Hindu Kush feels like a fortress.

Where the Lines Blur: Reading the Map of the Hindu Kush Mountains

Most maps will show you that the range starts in the west near the Bamyan Valley and stretches all the way to the high plateaus of the Wakhan Corridor. But maps are kinda liars. They don't show you the verticality. You aren't just moving north or south; you are moving thousands of feet up and down through passes that have swallowed entire armies.

The highest point is Tirich Mir. It sits at 7,708 meters (about 25,289 feet) in the Chitral District of Pakistan. On a topographical map, this peak looks like a giant white tooth. Surrounding it are dozens of other peaks over 7,000 meters. If you’re looking at a physical map, notice how the density of the ridges increases as you move east. The western part is lower, more accessible, but as you hit the eastern Hindu Kush, the terrain becomes a labyrinth of glaciers and granite.

The map is also a political headache. It crosses through Afghanistan and Pakistan, touching the fringes of Tajikistan and China. The Durand Line—the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan—cuts right through these mountains. It’s a line drawn on paper by the British in 1893 that the mountains themselves completely ignore. Tribal groups, snow leopards, and winds don’t care about the ink on the map.

The Passes That Changed History

Maps aren't just about peaks; they're about the holes in the peaks. The passes.

Take the Khyber Pass. It’s the most famous notch on any map of the Hindu Kush mountains. It’s the gateway. For centuries, if you wanted to conquer India or trade silk, you had to squeeze through this narrow gap. Then there’s the Salang Pass. Today, there’s a tunnel there—the Salang Tunnel—which is one of the highest road tunnels in the world, sitting at roughly 3,400 meters.

Before that tunnel? Crossing was a nightmare.

📖 Related: Tipos de cangrejos de mar: Lo que nadie te cuenta sobre estos bichos

In the winter, these passes are death traps. Snow doesn't just fall; it buries. A standard road map might show a line connecting Kabul to Mazar-i-Sharif, but that line is often theoretical from November to April. Avalanches are the real landlords here.

The Geologic Reality Beneath the Paper

Why does the Hindu Kush look so jagged on a map? It’s because the Indo-Australian plate is still shoving itself under the Eurasian plate. It’s a slow-motion car crash that has been happening for millions of years. This isn't stable ground.

The Hindu Kush is one of the most seismically active regions on Earth. When you look at a map showing earthquake epicenters, the Hindu Kush lights up like a Christmas tree. The "Hindu Kush Nest" is a specific zone where deep-seated earthquakes happen constantly. We are talking about shocks occurring 200 kilometers below the surface.

It’s weird.

Usually, earthquakes happen near the surface. But here, the crust is being dragged down so deep that it snaps under immense pressure. So, when you look at a map of the Hindu Kush mountains, imagine it’s a living thing that’s still growing, shifting, and occasionally shaking the ground hard enough to level cities.

Water: The Map’s Lifeblood

If you follow the blue lines on the map, you’ll see where the real power lies. The Hindu Kush is the water tower of Central Asia. The Helmand River, the Kabul River, and the Konar River all start here. They are fed by melting glaciers.

But there’s a problem. The glaciers are shrinking.

👉 See also: The Rees Hotel Luxury Apartments & Lakeside Residences: Why This Spot Still Wins Queenstown

Recent studies by organizations like ICIMOD (International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development) show that these "Third Pole" glaciers are retreating faster than we thought. On a 1970s map, the glaciated area would look significantly larger than it does on a satellite map today. This isn't just a geography fact; it's a looming water crisis for millions of people downstream in Kabul and the Indus Valley.

Navigating the Cultural Map

The mountains have created "pockets" of humanity. Because travel is so hard, cultures have stayed isolated for thousands of years.

Look at the Kalash Valleys in Pakistan. On a map, they are just tiny slivers near the Afghan border. But inside those valleys, the people have a completely unique religion, language, and culture that looks nothing like the surrounding Islamic regions. They’ve stayed "hidden" because the Hindu Kush acted as a shield.

Then you have the Wakhan Corridor. It’s that weird "finger" of land on the map of Afghanistan that reaches out to touch China. It was created as a buffer zone between the Russian and British Empires during the "Great Game." Even today, the people living there, the Wakhi, live a life that feels disconnected from the modern world. They are the high-altitude nomads of the map.

What Most People Get Wrong

People think the Hindu Kush is just a subset of the Himalayas. It’s not.

While they are part of the same massive mountain complex, the Hindu Kush has its own distinct tectonic history. It’s also much more arid. You won't find the lush, tropical foothills of the Eastern Himalayas here. This is a landscape of stark contrasts: blinding white snow against deep, dark rock and bright turquoise glacial lakes.

Also, the name itself is a point of contention. Some say "Hindu Kush" means "Killer of Hindus," referring to the Indian slaves who died in the cold while being transported to Central Asia. Others, like the traveler Ibn Battuta, supported this grim origin. However, some modern linguists suggest it might be a corruption of "Hindu Koh," meaning "Mountains of India." The map carries the weight of that history.

✨ Don't miss: The Largest Spider in the World: What Most People Get Wrong

Mapping the Future of the Range

What does a map of the Hindu Kush mountains look like in 2026? It looks like a region in transition.

Mining companies are looking at the map with greedy eyes. There are massive deposits of copper, lithium, and rare earth minerals buried under that rock. In Afghanistan, the Mes Aynak site is one of the largest untapped copper deposits in the world. But it’s also a Buddhist archaeological treasure. The map is now a battleground between economic survival and cultural preservation.

Modern mapping tech—LiDAR and high-resolution satellite imagery—is finally revealing what’s actually in the deep canyons. We are finding lost Silk Road outposts and measuring glacial melt down to the centimeter. But even with all this tech, the Hindu Kush remains one of the least explored places on the planet.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you are actually planning to use a map of the Hindu Kush mountains for travel or research, keep these realities in mind:

- Trust Topo, Not Roads: Never rely on a standard road map. You need topographic maps with contour lines. A 10-mile distance on a flat map could actually be a 15-hour trek due to vertical gain.

- Check the Season: Mapping "accessibility" is seasonal. Passes like the Lowari (before the tunnel) or the Shandur Pass are closed for half the year.

- Acknowledge the Buffer: If you are looking at the border regions, remember that "No Man's Land" is a real thing here. GPS can be unreliable in deep, narrow gorges where satellite signals are blocked by granite walls.

- Digital Tools: Use apps like Fatmap or Google Earth Pro for 3D visualization. Seeing the "folded" nature of the Hindu Kush is the only way to understand why it was never fully conquered.

The Hindu Kush isn't just a destination; it's a barrier that has shaped the genetics, languages, and religions of an entire continent. When you study the map, you aren't just looking at geography—you're looking at the blueprint of Central Asian history.

To truly understand this region, start by tracking the rivers from their source in the high eastern peaks. Follow the water, and you'll find the civilizations. Follow the ridges, and you'll find the legends. The map is just the beginning of the story.

Check the latest satellite updates from the Copernicus Open Access Hub if you want to see real-time snow cover changes across the range. It’s the best way to see the "wall" as it exists right now.