California is a weird place when it comes to water. If you look at a map of San Joaquin River, you aren't just looking at a blue line on a piece of paper or a digital screen; you’re looking at the central nervous system of the state’s massive agricultural machine. It's complicated. Honestly, it’s a bit of a mess. Most people think a river is a simple thing that flows from a mountain to the sea, but the San Joaquin is more of a "plumbing system" these days than a wild waterway.

It starts high. Real high. We’re talking over 10,000 feet up in the Sierra Nevada, specifically at Thousand Island Lake. From there, it tumbles down through the granite peaks, but by the time it hits the valley floor, things get strange. The water gets diverted, pumped, siphoned, and sometimes, the river just flat-out disappears.

Reading the Map of San Joaquin River from High Sierra to the Delta

When you pull up a map of San Joaquin River, the first thing you notice is the curve. It runs south from the Sierras, then makes a hard right turn to head north through the Central Valley. It’s the second-longest river in California, trailing only the Sacramento River. But length doesn't mean flow.

For a huge stretch between the Friant Dam and the confluence with the Merced River, the "river" is often bone dry. Why? Because we take the water. The Friant-Kern Canal and the Madera Canal suck that Sierra snowmelt away to keep the citrus and almond groves of the southern valley alive. If you're looking at a map and wondering why the blue line looks so thin or dashed in some places, that’s your answer. It’s been "over-appropriated," which is just a fancy way of saying we’ve promised more water to people than the river actually has.

The Major Landmarks You’ll Spot

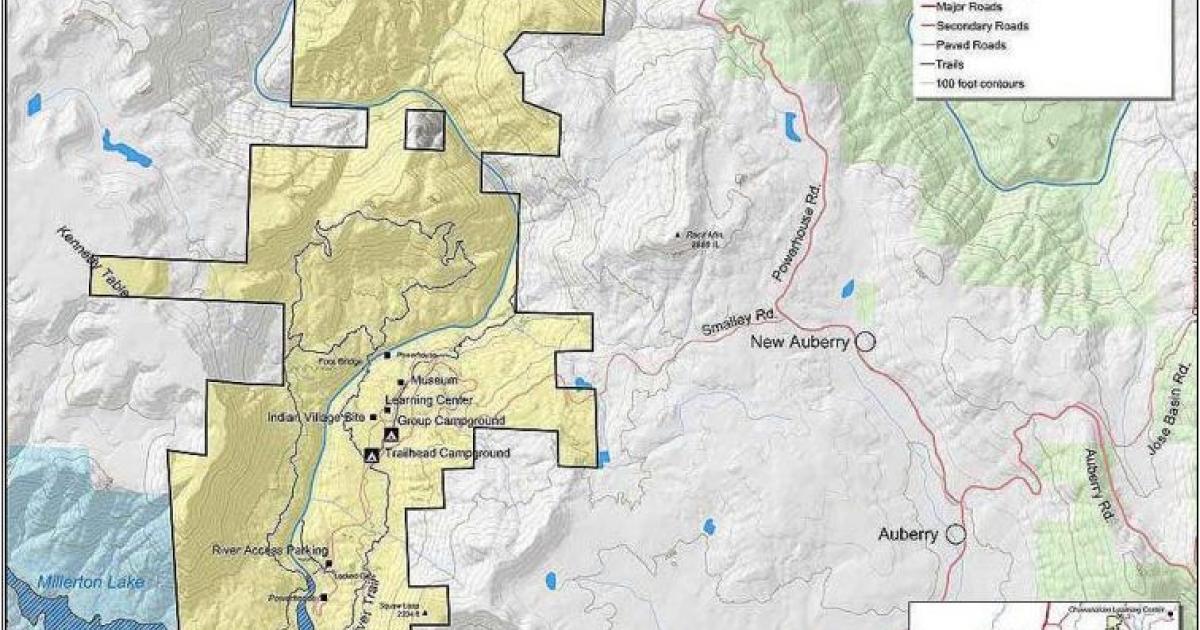

You’ve got a few key spots that define the river's geography. Millerton Lake is a big one. It’s the reservoir behind Friant Dam, just northeast of Fresno. This is where the river's "wild" life ends and its "working" life begins. Further downstream, you'll see where the tributaries join in—the Merced, the Tuolumne, and the Stanislaus. These three rivers are basically the life support system for the lower San Joaquin. Without them, the main stem would barely be a trickle by the time it reached Stockton.

Then there’s the Delta. The Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta is a massive, inverted triangle of islands and levees. It’s where the river finally meets the Sacramento River and heads out toward the San Francisco Bay. If you’re navigating this area, a standard map won't help much; you need a nautical chart. The channels are a maze. People get lost back there all the time because the "islands" are often below sea level, hidden behind giant dirt walls.

📖 Related: Food in Kerala India: What Most People Get Wrong About God's Own Kitchen

Why the Topography Matters More Than the Lines

Basically, the Central Valley is a bowl. The San Joaquin flows along the bottom of that bowl. But because the land is so flat—sometimes dropping only a few inches per mile—the river wants to meander. It wants to wander around and create wetlands. Humans, however, like things in straight lines. We’ve built hundreds of miles of levees to keep the river in its place.

If you compare a modern map of San Joaquin River to one from the 1850s, the difference is staggering. Back then, the valley was a patchwork of seasonal lakes and tule marshes. Today, it’s a grid. But the river remembers where it used to go. During "wet" years, like the massive floods we saw in late 2022 and early 2023, the river tries to reclaim its old territory. Places like the San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge near Modesto become massive inland seas again. It’s a reminder that our maps are more like "suggestions" to nature.

The Restoration Project: Putting Water Back

There is a massive effort underway called the San Joaquin River Restoration Program (SJRRP). It’s one of the biggest environmental do-overs in US history. The goal is to bring salmon back to the upper reaches of the river. To do that, they have to ensure there is actually water in the channel year-round.

This means the map of San Joaquin River is actually changing. New bypasses are being built. Old levees are being moved. If you’re looking at a map from ten years ago, it might already be out of date regarding where the water actually flows. They are literally re-engineering the river to act like a river again. It’s a weird paradox—using heavy machinery and engineering to create something "natural."

Navigation and Recreational Access

Can you actually boat on it? Sorta.

👉 See also: Taking the Ferry to Williamsburg Brooklyn: What Most People Get Wrong

In the lower reaches, near Stockton and the Delta, you can take a massive cargo ship up the deep-water ship channel. It’s surreal to see a giant vessel towering over the cornfields. But as you move south (upstream), it gets tougher. In the summer, you might be dragging your kayak over sandbars.

- The Delta Loop: Great for powerboats and fishing.

- George J. Hatfield State Recreation Area: Good for swimming and easy paddling when the flow is right.

- Friant to Skaggs Bridge: This is "Canoe Trail" territory, but you have to check the release levels from Friant Dam. If they aren't releasing water, you're walking.

The water quality is another thing to watch. Because the river collects runoff from thousands of acres of farmland, it can get high in salts and nitrates. It's not the pristine mountain water you see at the headwaters. By the time it hits the Delta, it’s been used and reused several times.

How to Use a Map to Understand Water Rights

This is where it gets nerdy but important. In California, water is gold. If you look at a map of San Joaquin River, you’ll see dozens of irrigation districts bordering the banks. These districts—like Westlands or Central California Irrigation District—have specific "points of diversion."

A map of the river is also a map of legal battles. Every bend in the river represents a different water right. Some of these rights go back to the 1800s. These "senior" rights holders get their water first, even in a drought. Everyone else gets what’s left. When you see a dry riverbed on a map, you’re looking at the physical manifestation of a junior water right holder losing out.

The Impact of Subsidence

Here is a wild fact: the land around the San Joaquin River is sinking. It’s called subsidence. Because we’ve pumped so much groundwater out of the Central Valley, the earth is literally collapsing in on itself. In some places near the river, the ground has dropped 30 feet over the last century.

✨ Don't miss: Lava Beds National Monument: What Most People Get Wrong About California's Volcanic Underworld

This wreaks havoc on the river's gravity-fed flow. If the land sinks, the river can’t flow "downhill" as easily. Engineers have to constantly check their maps and surveys to figure out how to keep the water moving. It’s a constant battle against the literal sinking of the earth.

What Most People Get Wrong About the San Joaquin

Most people think the river is just a dirty canal. It’s not. Despite all the dams and the diversions, it’s still a living ecosystem. You’ve got Great Blue Herons, Chinook salmon (thanks to the restoration efforts), and the endangered Riparian Brush Rabbit.

Also, people think "South" means "Downstream." Not here. The San Joaquin is one of the few major rivers in the US that flows primarily north. If you're looking at a map of San Joaquin River and trying to figure out which way the current goes, remember: it’s trying to get to San Francisco, so it’s heading "up" the map.

Practical Steps for Explorers and Researchers

If you're planning a trip or doing a deep dive into the river's geography, don't just rely on Google Maps. It often misses the nuance of water levels.

- Check the CDEC: The California Data Exchange Center provides real-time flow data. If the gauge at Vernalis or Stevinson is low, the river is effectively a series of puddles.

- Use USGS Topo Maps: These show the old oxbows and "sloughs" that don't appear on standard road maps. It gives you a sense of where the river wants to be.

- Consult the SJRRP Site: If you want to see where new construction is happening for salmon passage, the San Joaquin River Restoration Program maps are the gold standard.

- Visit the San Joaquin River Parkway: If you're in Fresno, this is the best way to see the river up close in a way that’s actually accessible. They have great trail maps that show the "bluffs" overlooking the water.

The map of San Joaquin River is a document of California's ambition and its consequences. It shows how we turned a desert into an orchard, but it also shows the scars of that transformation. Whether you're a fisherman, a kayaker, or just someone trying to understand why California's water politics are so insane, the river is the best place to start. It’s the heart of the valley, even if that heart beats a little irregularly these days.

Explore the public access points at the San Joaquin River National Wildlife Refuge to see the most natural state of the lower river. Always verify current flow rates through the Department of Water Resources before attempting any water-based navigation, as conditions change hourly based on dam releases. Use the California Water Library for historical map overlays to compare the pre-industrial river to its current channelized state.