Look at a map of Rocky Mountains and you’ll see a massive, jagged spine that looks like it's trying to split North America in half. It’s huge. Honestly, the scale is hard to wrap your head around until you’re standing at the base of a 14,000-foot peak in Colorado or looking at the glacial silt in Alberta. But here is the thing: most people look at a map and think the Rockies are just one big continuous pile of rocks.

They aren't.

What we call "The Rockies" is actually a messy, beautiful collection of at least 100 separate ranges. It stretches more than 3,000 miles. It goes from the top of British Columbia and Alberta all the way down into New Mexico. If you’re planning a trip, or just trying to understand the geography, you’ve gotta realize that a map of Rocky Mountains is basically a map of several different climates, ecosystems, and geological "moods."

The North vs. The South: It's Not All the Same Rock

If you look at the northern section on a map of Rocky Mountains, specifically up in Canada, the peaks look different. They are "sharper." This is because of heavy glaciation. These mountains were carved by ice that was thousands of feet thick. When you move down into the Southern Rockies, like the Front Range in Colorado or the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in New Mexico, the peaks are often more rounded or blocky. The geology here is older and more about "uplift" than just ice carving.

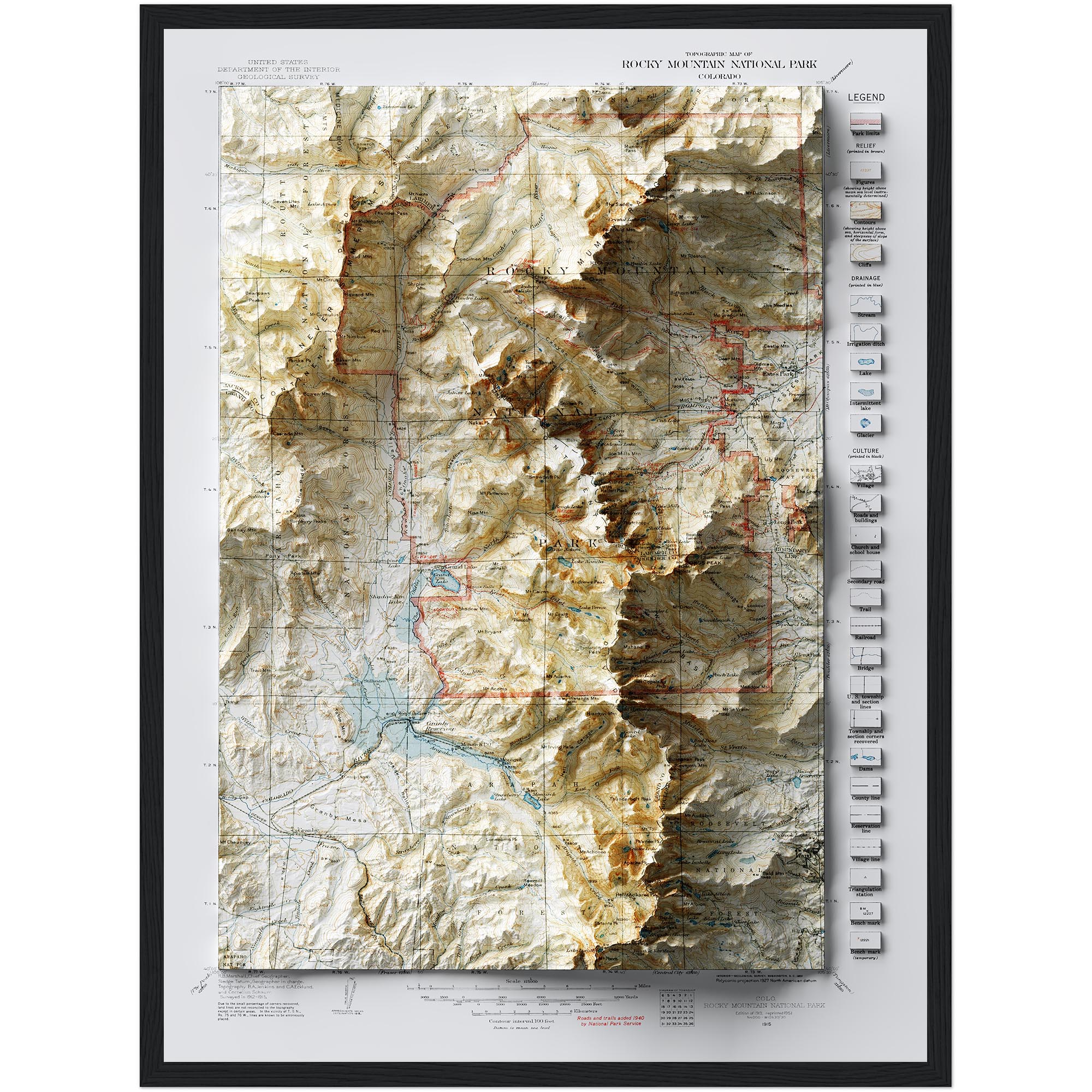

I’ve spent a lot of time looking at topo maps of the Tetons. They are the "youngest" part of the Rockies. They don't even have foothills. They just jump straight out of the ground. That’s why they look so dramatic on a map—the contour lines are basically right on top of each other. It’s vertical chaos.

The Continental Divide is the Real Boss

Every good map of Rocky Mountains features a dashed or highlighted line representing the Continental Divide. It’s the invisible line that decides the fate of a raindrop.

👉 See also: Full Moon San Diego CA: Why You’re Looking at the Wrong Spots

If a drop of water falls on the west side of that line, it’s headed for the Pacific. If it falls an inch to the east, it’s going to the Atlantic or the Gulf of Mexico. This isn't just a fun trivia fact. It dictates where the forests are. The west side usually gets more moisture. It’s greener. The east side? Often a rain shadow. It’s drier, browner, and more prone to wildfires. You can see this clearly on satellite maps; one side looks like a mossy carpet, the other looks like high-altitude desert.

Navigating the Major Hubs

You can't just "go to the Rockies." You have to pick a zone. Most people cluster around three or four main spots.

- The Canadian Rockies: Think Banff and Jasper. On a map, this is the northern tail. It’s where you find those turquoise lakes like Louise or Moraine. The color comes from "rock flour"—fine particles of silt suspended in the water.

- The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: This is the middle bit. It’s a massive volcanic plateau surrounded by mountains. It’s weird. You’ve got geysers sitting right next to snowy peaks.

- The Colorado High Country: This is the densest part of the map of Rocky Mountains. Colorado has 58 "fourteeners"—peaks over 14,000 feet. If you like thin air and alpine tundra, this is your spot.

- The New Mexico Tail: People forget the Rockies end in New Mexico. The Sangre de Cristo range brings the mountains down into a high-desert environment. It’s red dirt and pine trees.

Why Your GPS Might Lie to You

Modern digital maps are great, but in the Rockies, they can be dangerous. I’ve seen people try to follow a "road" on Google Maps that turns out to be a goat trail meant for a specialized 4x4.

The elevation changes are so extreme that a "short" distance on a 2D map might take four hours because you’re switching back and forth over a 12,000-foot pass. Always check the seasonal closures. Most of the high-altitude passes on a map of Rocky Mountains, like Trail Ridge Road in Rocky Mountain National Park, are closed from October to June. If you ignore the "closed" sign on your screen, you’re going to have a very bad time.

The Misconception of "The Foothills"

A lot of people think the mountains just start. They don't. On a map, look for the "High Plains." This is the flat area that slowly tilts upward until—bam—the Flatirons or the Front Range hits you. This transition zone is where most of the wildlife hangs out. If you want to see elk or bears, you don’t always go to the highest peak. You go to the edges.

✨ Don't miss: Floating Lantern Festival 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

Using a Map to Understand the Ecosystems

If you’re looking at a physical map of Rocky Mountains, pay attention to the colors.

- Green (Below 9,000 ft): This is the Montane zone. Ponderosa pines and Douglas firs.

- Darker Green (9,000 - 11,000 ft): Subalpine. This is the "snow forest." Spruce and fir trees that are skinny so they don't break under 20 feet of snow.

- Grey/Brown (Above 11,500 ft): Alpine Tundra. This is above the treeline. It’s basically the Arctic moved to the middle of the continent. Nothing grows taller than a few inches.

It’s a different world up there. The air is 30% thinner. If you aren't used to it, your head will throb. Drink water. Then drink more water.

Real Data: The Scale of the Range

Let's talk numbers. The highest point is Mount Elbert in Colorado. It sits at 14,440 feet. The range itself is up to 300 miles wide in certain spots. That’s a lot of space to get lost in. When you look at a map of Rocky Mountains, you’re looking at the headwaters for the Colorado, Columbia, Missouri, and Rio Grande rivers. The entire West depends on the snow that falls on these maps.

If the snowpack is low, the West goes thirsty. It’s that simple.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you’re looking at a map of Rocky Mountains to plan a trip, stop looking at the whole thing. Focus on a 50-mile radius.

🔗 Read more: Finding Your Way: What the Tenderloin San Francisco Map Actually Tells You

Pick a "basecamp" town.

- Canmore/Banff for the north.

- Whitefish for Glacier National Park.

- Jackson for the Tetons.

- Estes Park or Breckenridge for the Colorado heartland.

- Taos for the southern tip.

Check the topo lines. If they are close together, you are hiking uphill. If there’s a blue line, there’s water, but don’t drink it without a filter because of Giardia—a nasty little parasite that lives in even the clearest-looking streams.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Mountain Adventure

First, download offline maps. Cell service is non-existent once you dip into a canyon. Use an app like Gaia GPS or OnX Backcountry; they show public vs. private land boundaries which is huge if you're exploring off-trail.

Second, get a paper map. National Geographic’s "Trails Illustrated" series is the gold standard for the Rockies. They are waterproof and tear-resistant. When your phone dies because the cold drained the battery in twenty minutes, that paper map is your best friend.

Third, pay attention to the aspect. On a map of Rocky Mountains, north-facing slopes hold snow way longer. If you’re hiking in June, a south-facing trail might be dry, while the north side of the same mountain is still under six feet of slush.

Finally, check the "SNOTEL" data. This is a network of automated sensors across the Rockies that tells you exactly how much snow is on the ground at various elevations. It’s the most accurate way to know if a trail is actually hikable or if you need snowshoes. Don't just trust a generic weather report for the nearest town; the weather at the trailhead is usually ten degrees colder and twice as windy.