Texas is big. You know that. Everyone knows that. But when you start looking at a map of northern texas, things get a little complicated because nobody can quite agree on where "North Texas" actually ends. If you ask someone in Dallas, they’ll point at the skyscrapers and the sprawl. Ask a rancher in Amarillo, and they’ll laugh, telling you that you’re still in the South until you’ve hit the Caprock Escarpment.

It’s a massive, confusing, and beautiful chunk of land. Honestly, most people just see a sea of red lines and green blobs on a GPS and assume it’s all flat prairie. They're wrong. The geography of this region dictates everything from the local economy to why your allergies act up in November.

The Three Worlds on One Map

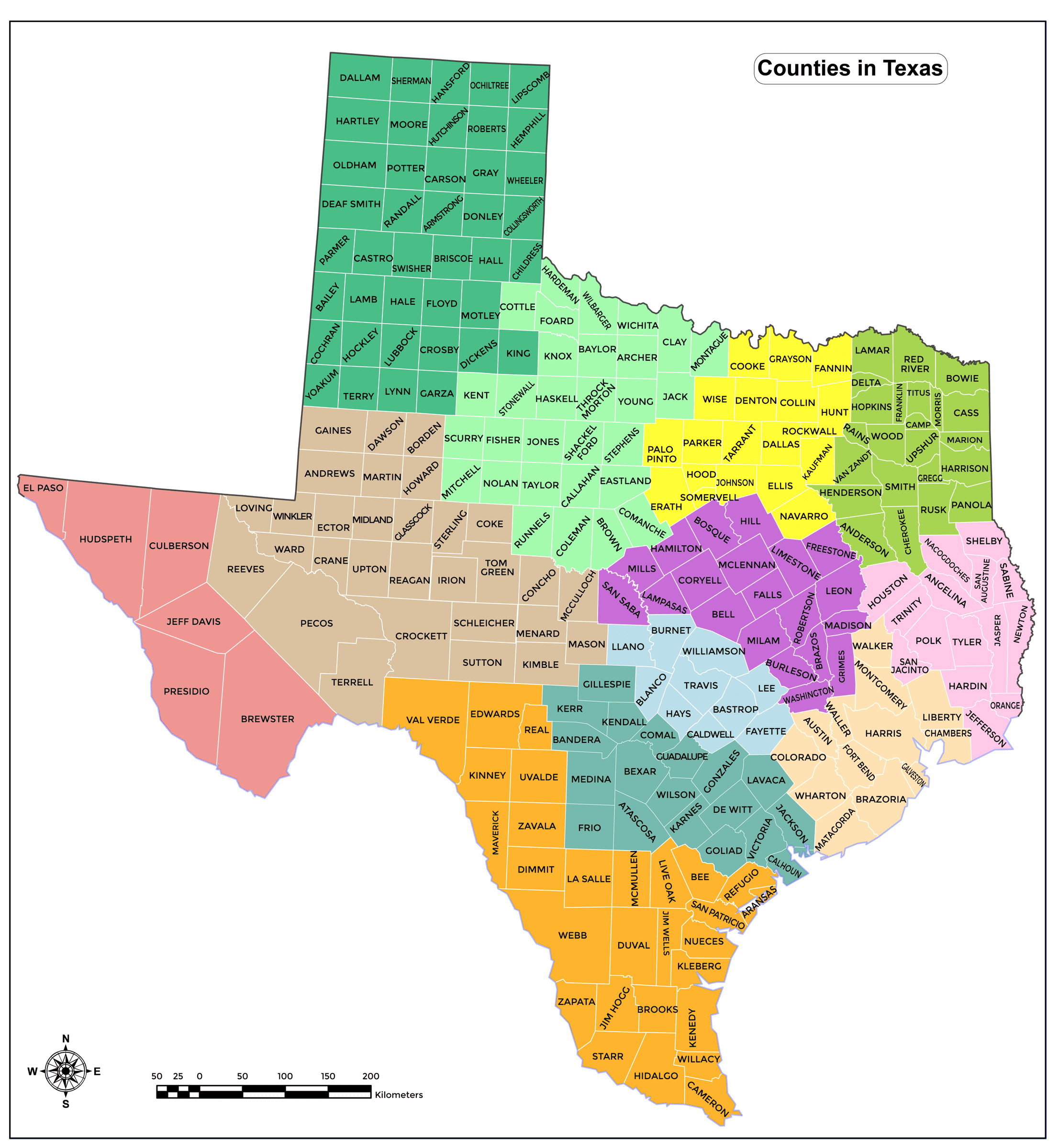

If you look closely at a topographical map of northern texas, you aren’t looking at one region. You’re looking at three distinct geological personalities. First, you’ve got the Piney Woods creeping in from the east near Texarkana. Then, the Cross Timbers—that rugged, scrubby belt of oak that hits the DFW metroplex. Finally, you move west into the Rolling Plains and eventually the High Plains of the Panhandle.

Texas geologists like those at the Bureau of Economic Geology have spent decades mapping the "Llano Estacado," which is basically a massive mesa that rises up as you head toward New Mexico. It’s one of the largest such formations in North America. When you’re driving west on I-40 and the elevation suddenly jumps? That’s not a glitch in your cruise control. You've just climbed the Caprock.

Why the Metroplex Dominates the View

For most travelers, the map of northern texas is dominated by the massive "H" shape of the Dallas-Fort Worth metro area. It’s a concrete giant. You have I-35 splitting into 35E and 35W, creating a loop that traps millions of people in daily commutes.

🔗 Read more: Sheraton Grand Nashville Downtown: The Honest Truth About Staying Here

But here’s the thing: the map hides the history. Fort Worth was the "Where the West Begins" line for a reason. West of that line, the water gets scarce and the trees get shorter. Dallas was the banking center; Fort Worth was the cattle stop. Even today, the way the highways are laid out reflects those 19th-century trade routes. You can see the ghost of the Chisholm Trail if you know which backroads to follow near US-81.

The Panhandle: A Different Kind of North

If you draw a line north of Wichita Falls, you enter the Panhandle. This is the "true" North Texas for many, though locals usually just call it the Panhandle to avoid being lumped in with the suburbanites in Plano.

The map of northern texas in this area is a grid. It’s relentlessly straight. Why? Because the land is so flat that the original surveyors in the late 1800s didn't have to navigate around mountains or massive lakes. They just laid out sections and townships like a giant chessboard.

- Palo Duro Canyon: This is the big surprise. It’s the second-largest canyon in the United States, and on a standard road map, it looks like a tiny jagged crack south of Amarillo. In reality, it’s a 120-mile-long gash in the earth that drops 800 feet.

- The Red River: This serves as the jagged northern border with Oklahoma. It’s notoriously fickle. The riverbed is often more sand than water, but it has caused decades of legal battles between the two states regarding exactly where the border lies.

Climate Zones You Can See From Space

You can actually see the rainfall patterns on a satellite map of northern texas. It’s a gradient of green to brown. The eastern edge gets about 45 inches of rain a year. By the time you hit the New Mexico border, you're looking at 15 inches.

💡 You might also like: Seminole Hard Rock Tampa: What Most People Get Wrong

This moisture divide is why the crops change. In the east, you see timber and hay. In the middle, it's cattle and wheat. Out west? Cotton and wind turbines. Texas leads the nation in wind power, and if you look at a modern energy map of the region, the density of turbines near Sweetwater and Spearmans is staggering. They've mapped the wind just as carefully as the soil.

The Urban Sprawl Problem

We have to talk about Denton and Collin Counties. If you look at a map of northern texas from 1990 versus today, the change is violent. Cities like Frisco and McKinney were tiny dots; now they are massive hubs of commerce. The "Golden Corridor" along the Dallas North Tollway has fundamentally shifted the center of gravity for the whole state.

This isn't just trivia. It affects how you travel. If you're using an old paper map—and yes, some people still do—half the exits in Celina or Prosper won't even exist on your page. The infrastructure is moving faster than the printers can keep up.

Navigation Realities for Travelers

Forget what the GPS says for a second. If you’re navigating the northern reaches of the state, you need to understand the "FM" and "RR" system.

📖 Related: Sani Club Kassandra Halkidiki: Why This Resort Is Actually Different From the Rest

Farm to Market (FM) roads and Ranch to Market (RR) roads are the lifeblood of the rural map of northern texas. They aren't just backroads; they are high-speed arteries for the agriculture industry.

- Watch for heavy machinery.

- Don't expect cell service in the "breaks" (the rugged eroded areas near river valleys).

- Fuel up in the bigger hubs like Childress or Vernon, because "towns" on the map might just be a grain elevator and a closed post office.

How to Actually Use a Map of Northern Texas

To get the most out of your trip or research, stop looking at the map as a flat image. See it as layers. There is the geological layer of the Edwards Plateau and the High Plains. There is the historical layer of the Butterfield Overland Mail route. And then there’s the modern layer of high-speed fiber optics and interstate commerce.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Route:

- Verify Your Destination: If you are looking for "North Texas," clarify if you mean the DFW Metroplex or the actual geographic north (the Panhandle). They are six hours apart.

- Check the Elevation: If you are towing a trailer, note the climb from the Rolling Plains to the High Plains (roughly between Wichita Falls and Amarillo). It’s a steady incline that eats fuel.

- Use Offline Maps: Download the region between Amarillo and Lubbock before you leave. The "dead zones" are real and can leave you stranded without a digital breadcrumb trail.

- Explore the Canyons: Don't stick to I-40. Take State Highway 207 through the Tule Canyon for some of the most dramatic views that most people miss because they stay on the main lines.

- Identify the River Crossings: The Red River has limited crossing points. If you miss your bridge in a place like Gainesville or Burkburnett, you might be driving fifty miles out of your way to find the next one.