You look at a standard map of lakes in the US and it looks like a blue-spotted mess. Honestly, most people just see a bunch of dots and think "cool, water." But if you actually dig into the hydrology, that map tells a story about the literal carving of the continent. It’s not just about where the fishing is good. It's about where the glaciers stopped, where the earth cracked open, and where we, as humans, decided to play God with concrete dams.

North America is soaked.

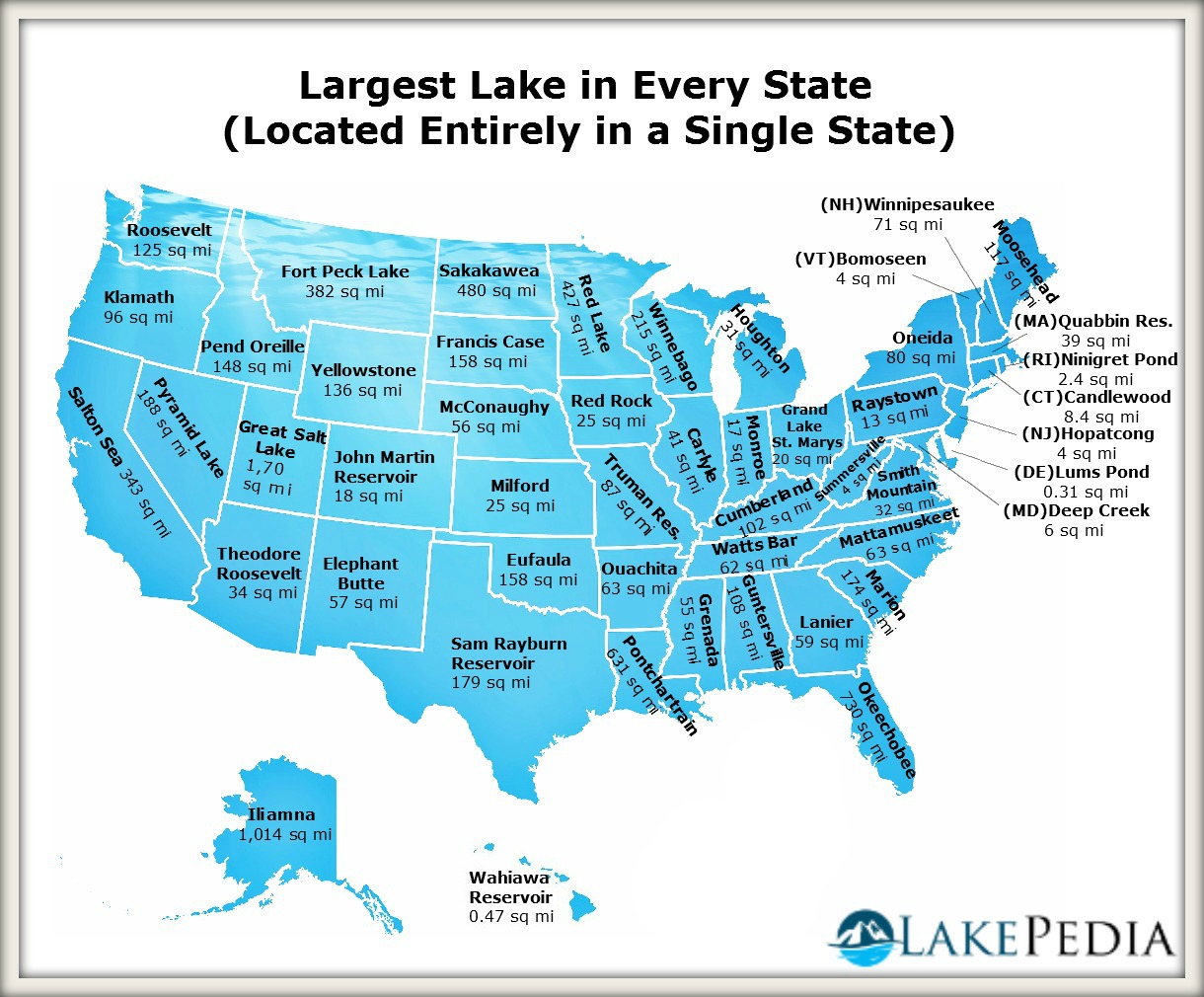

If you zoom into the Upper Midwest, the map looks like someone tipped over a giant bucket of water. Minnesota claims ten thousand lakes, but they're actually lowballing it; there are over 11,800 bodies of water over ten acres there. Then you look at a state like Maryland, and the map goes almost dry. Did you know Maryland has zero natural lakes? Not a single one. Every bit of still water in that state is man-made. That kind of contrast is exactly why a flat map of lakes in the US can be so misleading if you don't know what you’re looking at.

The Glacial Scarring of the North

Look at the top of the map. The Great Lakes—Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario—dominate the visual landscape. They hold about 21% of the world's surface fresh water. That’s an insane statistic. They weren't always there, obviously. About 20,000 years ago, the Laurentide Ice Sheet was basically a mile-thick bulldozer. As it retreated, it gouged out the earth and filled the holes with meltwater.

This glacial activity is why the "map of lakes in the US" is so top-heavy.

Wisconsin and Michigan are riddled with "kettle lakes." These happened when giant chunks of ice broke off the main glacier, got buried in sediment, and then melted. It’s like a pockmarked face. When you're driving through the Northwoods, you're basically driving over a graveyard of ancient ice. The biology in these lakes is specific too. You've got cold-water species like lake trout and walleye that have survived in these deep, dark pockets for millennia.

The Great Basin and the Salty Outliers

Move your eyes west. Past the Rockies, the map gets weird.

💡 You might also like: Garden City Weather SC: What Locals Know That Tourists Usually Miss

In the Great Basin—mostly Nevada and parts of Utah—the water doesn't go to the ocean. It just sits there until it evaporates. This is why the Great Salt Lake exists. It’s a remnant of the prehistoric Lake Bonneville, which was once almost as big as Lake Michigan. Now, it’s a hyper-saline puddle by comparison. If you look at a map of lakes in the US from fifty years ago versus today, the Great Salt Lake is shrinking at a terrifying rate.

It’s a different kind of lake. You can't drink it. You can barely swim in it without bobbing like a cork. And it’s not alone. Pyramid Lake in Nevada is another remnant of a massive ancient sea. These western lakes are often "terminal," meaning they are the end of the line for any river that feeds them.

Why the South Looks Different on the Map

The Southeast is a whole different beast. If you look at a map of lakes in the US in states like Georgia, Tennessee, or Alabama, you’ll notice something. The lakes are long and skinny. They look like snakes.

That’s because they aren't natural.

Almost every major lake in the South is a reservoir. They are flooded river valleys created by the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) or the Army Corps of Engineers. Lake Lanier in Georgia? Man-made. Lake Cumberland in Kentucky? Man-made. These were created for hydroelectric power and flood control during the mid-20th century. While they’re beautiful and great for bass fishing, they don’t have the same geological history as the deep glacial lakes of the North. They are drowned forests and submerged towns.

There is one major exception: Lake Okeechobee in Florida. It’s huge, it’s shallow, and it’s natural. It’s basically a giant limestone saucer that collects water from the Kissimmee River and slowly spills it into the Everglades. It's only about 9 feet deep on average, which is wild for a lake that covers 730 square miles.

📖 Related: Full Moon San Diego CA: Why You’re Looking at the Wrong Spots

The Deepest Pits: Crater Lake and Tahoe

We have to talk about the outliers. The ones that don’t fit the "dots on a map" vibe.

Crater Lake in Oregon is the deepest lake in the United States. It’s nearly 2,000 feet deep. On a map of lakes in the US, it looks like a tiny blue eye. It formed about 7,700 years ago when Mount Mazama collapsed. There are no inlets. No rivers run into it. The water comes entirely from rain and snow, which is why it’s some of the clearest water on the planet. If you ever get the chance to stand on the rim, the blue is so intense it looks fake.

Then there’s Lake Tahoe on the California-Nevada border. It’s a fault-trough lake. The mountains went up, the ground between them sank, and water filled the gap. It’s the second deepest in the US. Because it’s so deep and high up, it never freezes, despite the massive amounts of snow it gets.

The Impact of Humans on the Map

We keep changing the map.

Climate change and water diversion are literally deleting lakes. Lake Mead and Lake Powell are the most famous examples. They are massive reservoirs on the Colorado River, but they’ve spent the last two decades hitting "dead pool" levels. When you look at a map of lakes in the US today, these reservoirs are often depicted at their full capacity, but the reality on the ground is a ring of white "bathtub" stains on the canyon walls.

On the flip side, we’re also creating them. Farm ponds and small municipal reservoirs are popping up everywhere, though they rarely make it onto a national map.

👉 See also: Floating Lantern Festival 2025: What Most People Get Wrong

Surprising Lake Facts Most People Miss

- The deepest lake isn't one of the Great Lakes; it's Crater Lake.

- The state with the most shoreline isn't Florida—it's often argued to be Michigan or even Minnesota if you count every single lake edge.

- Alaska has over 3 million lakes. If you put Alaska on a map of lakes in the US to scale, it would make the Lower 48 look dry.

- Lake Champlain was briefly considered a Great Lake in 1898. It lasted about 18 days before Congress realized that was a bit of a stretch and stripped the title.

Navigating the Map for Your Next Trip

If you’re using a map of lakes in the US to plan a trip, stop looking at the size and start looking at the elevation and the "type."

If you want crystal clear water and don't mind it being freezing, head for the alpine lakes in the Cascades or the Rockies. These are often "tarn" lakes, formed in cirques by glaciers. They are tiny but stunning. If you want warm water for swimming, you need the reservoirs of the South or the shallow glacial lakes of Indiana and Ohio.

The Great Lakes are basically inland seas. They have shipwrecks, tides (well, seiches), and weather systems that can sink a thousand-foot freighter. Don't treat Lake Superior like a local pond. It’s dangerous.

Actionable Steps for Lake Explorers

Stop relying on the generic blue blobs on Google Maps. If you want to actually understand the water you're visiting, follow these steps:

- Check the Bathymetry: Use tools like the NOAA Lake Ontario or Michigan bathymetry maps to see the underwater topography. It tells you where the fish hide and where the dangerous drop-offs are.

- Verify Access: Many lakes on a map are surrounded by private property. Use an app like OnX or a state-specific DNR (Department of Natural Resources) map to find public boat ramps and piers.

- Monitor Water Levels: If you're heading West, check the US Bureau of Reclamation website for real-time reservoir levels. A lake on a map might be a mudflat in person during a drought.

- Look for "Impaired Waters": Before you jump in, check the EPA's "How's My Waterway" tool. It will tell you if a lake has issues with algae blooms or mercury, which a standard map won't show.

- Identify the Source: Always look at what flows into the lake. A lake fed by a protected mountain stream is a different experience than one fed by agricultural runoff or urban storm drains.

The map of lakes in the US is a living document. It’s a snapshot of a moment in time where the climate, the geology, and human engineering have met. Whether you're looking for a quiet spot to paddle a canoe or a massive expanse to sail, understanding the "why" behind those blue shapes makes the journey a lot more interesting. Don't just look at the map—read it.