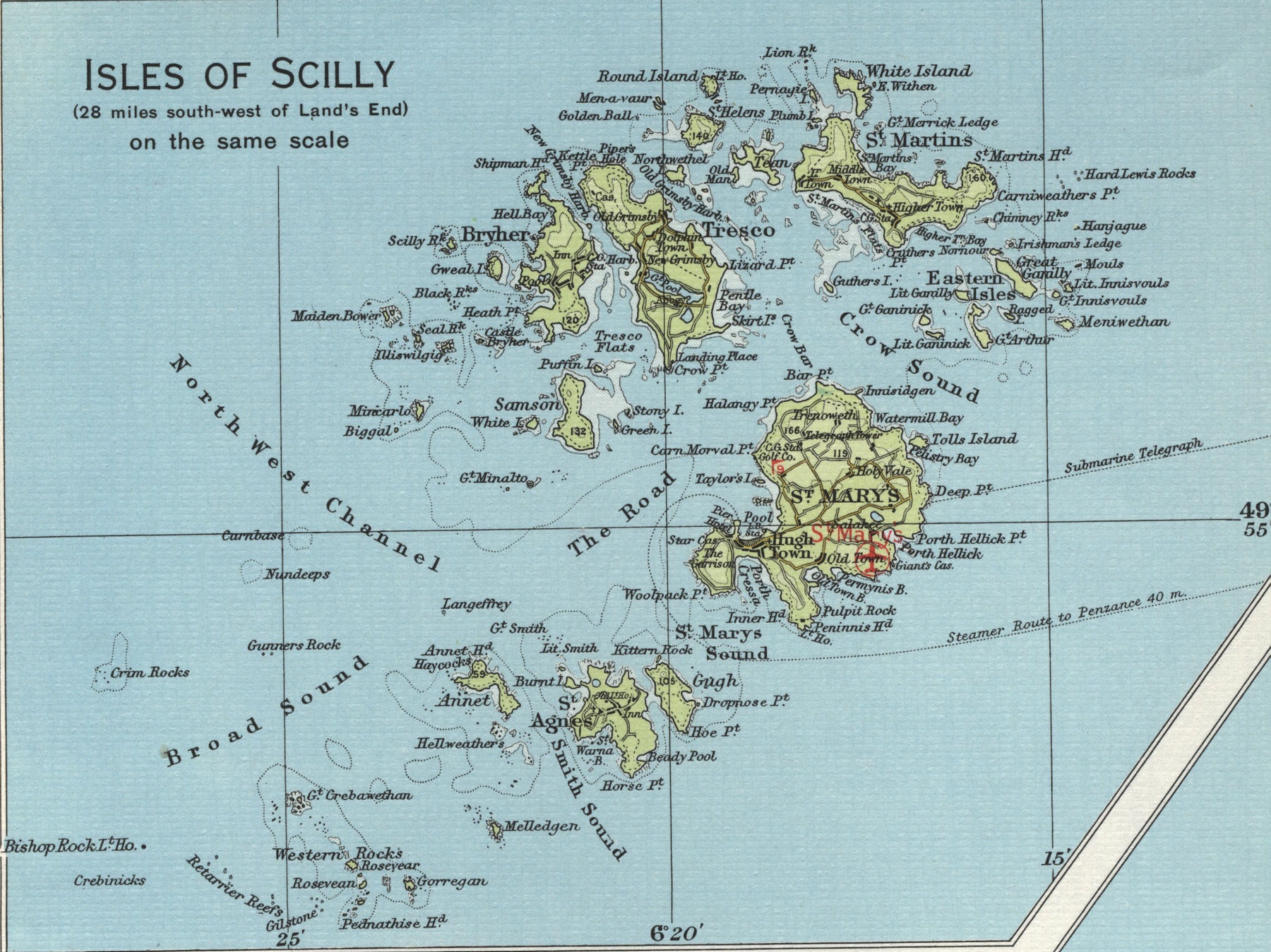

You’re standing on a pier in Penzance. The Scillonian III is humming. You look at a map of Isles of Scilly and think, "Okay, five inhabited islands, a bunch of rocks, looks simple enough."

It isn't.

Most people treat the Scillonian archipelago like a standard holiday destination where a GPS coordinate and a post code get you to dinner. They’re wrong. These islands, sitting 28 miles off the coast of Cornwall, are a shifting puzzle of granite and tide. If you rely on a basic digital map of Isles of Scilly, you’re going to miss the actual magic—or worse, get stuck in the mud in the middle of a channel that was deep blue water two hours ago.

The Geography of a Submerged World

Look at the shape of the islands. St Mary’s is the big one, the hub. Then you’ve got Tresco, Bryher, St Martin’s, and St Agnes. But look closer at a high-quality Ordnance Survey map. You’ll see vast expanses of pale yellow between the islands. That’s sand.

Basically, the Scillies are a drowned landscape.

Thousands of years ago, this was likely one large landmass called Ennor. As sea levels rose, the valleys became the seafloor. When the tide goes out today, the "map" changes entirely. You can literally walk between some of these islands. People do it. They trek from Bryher to Tresco during the low spring tides, picking their way across the sandbars while carrying a glass of prosecco. It’s surreal. But if your map doesn't show the bathymetry—the depth of the water—you’re basically flying blind.

Why St Mary's Isn't the Only Story

Everyone starts at Hugh Town. It’s the capital, if you can call a place with one main street a capital. On a map of Isles of Scilly, St Mary’s looks like a solid anchor. It has the airport. It has the quay. But the real geography buffs head for the Garrison.

The Garrison is a massive fortification on the western edge of St Mary's. If you walk the perimeter path, you can see the entire archipelago laid out like a physical 3D map. You see the Western Rocks, where the Gilstone Reef claimed the lives of over 1,400 sailors in 1707. That disaster, led by Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, happened because they didn't have an accurate map—or rather, they didn't know their longitude. It’s the reason the Longitude Act was created.

🔗 Read more: Madison WI to Denver: How to Actually Pull Off the Trip Without Losing Your Mind

Maps here aren't just for tourists; they are written in blood and shipwreck timber.

Understanding the "Off-Islands" Layout

Each island has a distinct personality that a paper map struggles to convey.

Tresco is the manicured one. It’s private. On the map, you’ll see the Abbey Gardens marked clearly. It’s a sub-tropical paradise because the island sits in the path of the North Atlantic Drift. You've got succulents and palm trees that have no business being in the UK.

Then there’s Bryher. Just across the channel.

On a map of Isles of Scilly, Bryher looks tiny, almost fragile. But go to Hell Bay on the rugged west side. The Atlantic hits it with everything it’s got. There is no land between that rocky shore and North America. It’s brutal. It’s loud. It makes the map feel like a lie because a two-dimensional drawing can't capture the scale of those swells.

- St Martin's: Famous for the Daymark. It’s a red and white striped tower. On your map, it’s a tiny dot on the eastern end. In reality, it’s the first thing sailors see when approaching from the east.

- St Agnes: The most southerly. It’s joined to the island of Gugh by a sandbar called a tombolo. This bar is only visible at low tide. If your map of Isles of Scilly doesn't have a tide table attached, you’re basically guessing.

- Samson: The ghost island. Look for the twin hills (North and South Hill) on the map. People lived there until 1855. Now, only ruins remain. It’s eerie.

The Problem With Digital Navigation Here

Google Maps is great for London. It sucks for the Scillies.

Why? Because Google doesn't understand "inter-island boating." The maps often lack the small, seasonal tracks that locals use. If you’re trying to find your way to Beady Pool on St Agnes to look for 17th-century terracotta beads from a shipwreck, Google might just show you a green blob.

💡 You might also like: Food in Kerala India: What Most People Get Wrong About God's Own Kitchen

You need the OS Explorer Map 101. That’s the gold standard. It shows every cairn, every prehistoric burial chamber, and every tiny cove.

Honestly, the best way to use a map of Isles of Scilly is to cross-reference it with the boat boards on the St Mary's quay. Every morning, the boatmen chalk up where the "Association" boats are going. The tides dictate the schedule. If the tide is low, the boat might drop you at a different pier than you expected. Suddenly, your planned route is backward. You have to be flexible. You have to be okay with the map being a suggestion rather than a rule.

Hidden Details You’ll Miss Without a Good Map

There are over 140 islands in total. Only five are inhabited.

If you look at the northern part of a map of Isles of Scilly, you’ll see the Eastern Isles. Places like Ganilly and Arthur. They look like mere specks. But these are essential habitats for grey seals. If you take a boat out there, you’re entering a maze of rocks that has stayed unchanged since the Bronze Age.

Prehistoric Scilly

The islands have one of the highest densities of prehistoric remains in Europe. Look for "Entrance Graves" on your map. There are dozens. Bant’s Carn on St Mary’s is a classic. You’re walking through a landscape that was mapped out by people 4,000 years ago using stones and stars.

The complexity is staggering. On St Martin’s, there’s a place called Knackyboy Cairn. Incredible name, right? It’s a burial chamber where they found glass beads and bronze tools. These sites are often just a small symbol on a map, but when you stand there, looking out over the blue water toward the next island, you realize the "map" used to include valleys that are now 20 feet underwater.

Practical Advice for Navigating the Islands

Don't just buy a postcard map and call it a day.

📖 Related: Taking the Ferry to Williamsburg Brooklyn: What Most People Get Wrong

If you want to actually see the islands, get a waterproof map case. The weather turns fast. One minute it’s Caribbean blue, the next it’s a grey mist that swallows the landmarks.

- Check the Datum: Make sure you understand the difference between Mean High Water and Mean Low Water on your map. It’s the difference between a dry walk and a swim.

- The "Bar" Rule: If a map shows a sandbar (like the one to Gugh or the one between St Agnes and the Turkish Shore), never cross it if the tide is coming in. The water moves faster than you can walk.

- Appreciate the Scale: The whole archipelago is only about 6 miles across. You can walk the circumference of St Mary's in a few hours. But it’s a dense 6 miles.

Most people get wrong the idea that they need a car. You don't. There are almost no cars for tourists. You walk, you cycle, or you take a boat. Your map of Isles of Scilly is for your feet, not your wheels.

Actionable Next Steps for Your Trip

Stop looking at the map as a way to get from A to B. Use it to find the gaps. Look for the tiny uninhabited islands like Annet (where the puffins live) or the Western Rocks.

First, download a reliable tide app like "AnyTide" or check the local Admiralty charts online before you arrive.

Second, head to the Island Chart Lab or a local shop in Hugh Town and buy the physical OS Map 101. There is something about holding the paper in the wind that makes the geography click.

Third, plan your "Island Hopping" based on the wind direction. If the wind is coming from the west, the eastern shores of St Martin's will be like a millpond. Use the map to find shelter.

The Isles of Scilly aren't just a place you visit; they are a place you learn to read. The map is your first lesson. Once you understand that the blue parts aren't always blue and the yellow parts aren't always dry, you’re ready to actually see them.