If you're staring at a coast of Washington state map and thinking it looks like a simple straight line, you’re honestly missing the point. It’s jagged. It’s messy. It’s a literal graveyard of ships and a sanctuary for giant trees. Most people just see a border between land and the Pacific Ocean, but if you look closer at the topography, you start to realize why this 157-mile stretch of coastline is one of the most treacherous and beautiful places on the planet.

Western Washington doesn't do "gentle."

The geography here is a chaotic mix of tectonic subduction zones, ancient basalt flows, and rain-soaked temperate rainforests. When you trace your finger along the map, you’re looking at the edge of the North American plate. Just offshore, the Juan de Fuca plate is sliding underneath us, creating the very mountains that make this coast so dramatic. It’s a place where the dirt is literally moving, albeit very slowly, and the maps have to be updated more often than you'd think because the ocean is constantly reclaiming the land.

Navigating the Three Distinct Zones

You can't just treat the whole coast as one big beach. It doesn't work that way. Experts, like those at the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, generally divide the coast into three specific "personalities." If you don't understand these, you're going to end up at a rocky cliff when you wanted a sandy dunes walk.

The Long Beach Peninsula

Down south, near the Oregon border, things are relatively flat. This is the Long Beach Peninsula. It’s basically a 28-mile sandbar. It’s famous for being one of the longest contiguous beaches in the world, but it’s also a massive hub for the cranberry industry and oyster farming in Willapa Bay. On a map, this looks like a long, skinny finger pointing north. It’s the easiest part of the coast to drive, but it's also the most susceptible to king tides.

Ever seen a king tide? It’s wild. The water comes up so high it swallows the driftwood and occasionally the parking lots.

✨ Don't miss: Historic Sears Building LA: What Really Happened to This Boyle Heights Icon

The Grays Harbor and Central Coast

Move your eyes up the coast of Washington state map to the middle section. You’ll see a massive indentation. That’s Grays Harbor. This is the industrial heart of the coast, centered around Aberdeen and Hoquiam. It’s where the timber used to flow out to the world. North of the harbor, you hit the "resort" towns like Ocean Shores and Seabrook. Seabrook is interesting because it’s a "new urbanist" town built from scratch on a bluff. It looks like a movie set, honestly. But the beach there is massive—wide enough that you could play a full game of football and not hit the water's edge at low tide.

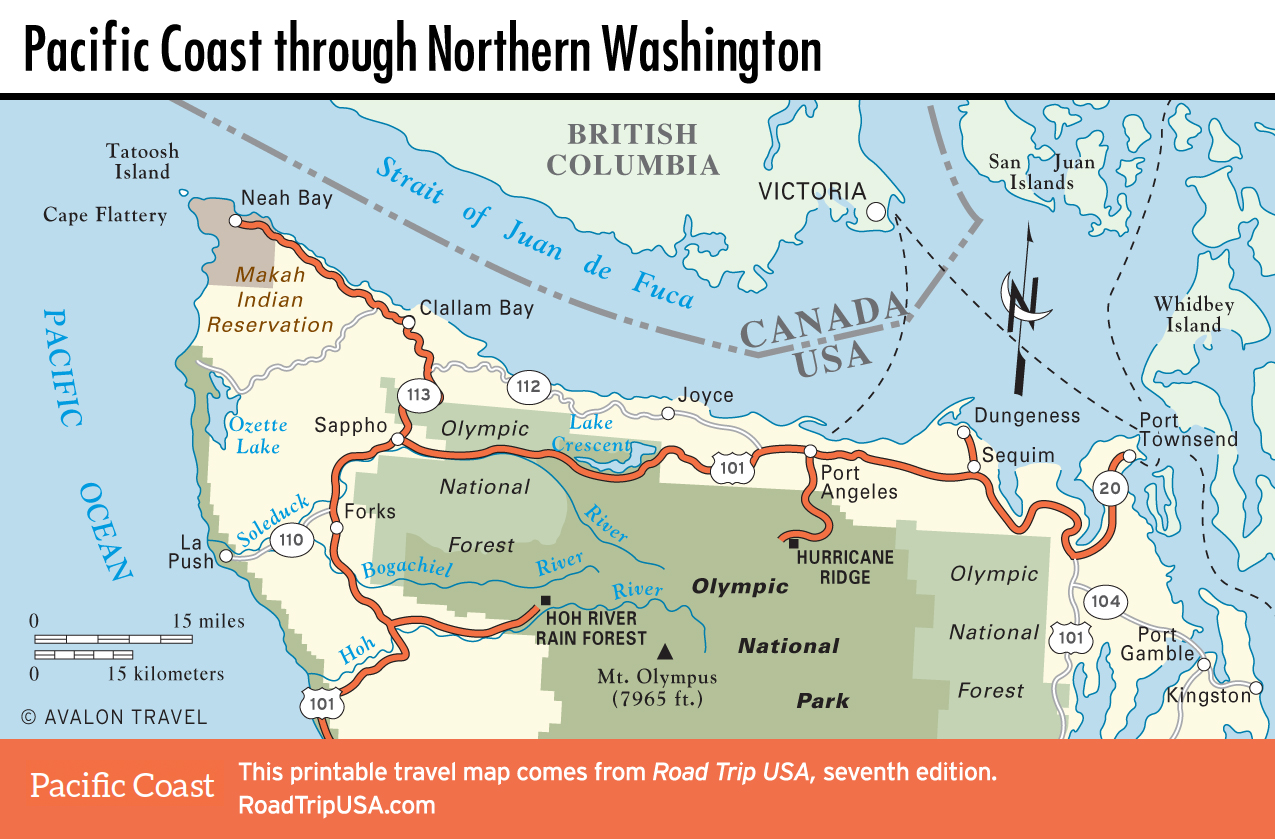

The Wild Olympic Wilderness

Then, everything changes. Once you cross the Quinault River, the roads basically give up. This is the Olympic National Park coastline. It’s one of the few places in the lower 48 where you can’t just drive along the shore. You have to hike. Places like Rialto Beach, Second Beach, and Shi Shi Beach are defined by "sea stacks." These are giant pillars of rock that got separated from the mainland by erosion. They look like jagged teeth sticking out of the surf.

Why the Map Can Be Lethal

People underestimate the Pacific. Seriously.

Looking at a map makes the distance from the trailhead to the water look short. But on the Washington coast, the "intertidal zone" is a battlefield. If you are hiking the north coast, you have to carry a tide chart. It’s non-negotiable. There are specific "headlands"—rocky points jutting into the sea—that are completely impassable at high tide. If you get timed out, you're stuck on a tiny strip of sand with a vertical cliff behind you and a rising ocean in front of you.

The National Park Service keeps a list of "danger zones" on their coastal maps. Places like Taylor Point or the trek around Cape Alava require you to know exactly when the water is receding. If the map shows a dotted line for a trail that goes over a headland, use the overland trail. Don't be the person who tries to beat the tide. The tide always wins.

🔗 Read more: Why the Nutty Putty Cave Seal is Permanent: What Most People Get Wrong About the John Jones Site

The Underwater Secrets of the Coast

If we could drain the water and look at the coast of Washington state map in 3D, it would look even crazier. Just off the coast of the Olympic Peninsula lies the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary. It covers about 3,188 square miles.

- Underwater Canyons: There are massive canyons like the Quinault Canyon that drop thousands of feet.

- Upwelling: Cold, nutrient-rich water rises from these depths, which is why we have so many whales and sea birds.

- Shipwrecks: The "Graveyard of the Pacific" extends up here. Hundreds of ships are mapped on the ocean floor, victims of the fogs and the "Columbia Bar" to the south.

Historically, the Makah, Quileute, and Quinault tribes have mapped these waters for thousands of years, long before European cartographers showed up with brass instruments. They knew where the halibut banks were and where the whale migrations happened. Modern maps are finally starting to incorporate more of this indigenous knowledge, especially regarding place names and sacred sites.

How to Actually Use a Coast of Washington State Map for a Trip

Don't just use Google Maps. It’s great for highways, but it's terrible for the coast. It won't tell you about the "log jams."

When you're at a place like Ruby Beach, the map shows a nice path to the water. In reality, that path is often blocked by thousands of bleached, massive cedar logs that have washed down the rivers and been tossed up by storms. You have to climb over them. It’s a workout.

If you're planning a visit, look for the Washington State Parks maps specifically. They highlight the "Hidden Coast" scenic byway (State Route 109). It’s a slower drive, but you actually see the ocean. Most of the main highway, US 101, actually stays inland because the terrain right on the water is too unstable for a major road.

💡 You might also like: Atlantic Puffin Fratercula Arctica: Why These Clown-Faced Birds Are Way Tougher Than They Look

The Tsunami Reality

Every map of the Washington coast printed in the last decade has blue and white signs or shaded areas marked "Tsunami Evacuation Zone." It’s something we live with here. Because of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, there is a standing risk of a major earthquake. If you’re at the beach and the ground shakes, you don't look at the map for the scenic route—you look for the "Tsunami Evacuation Route" arrows. Towns like Ocean Shores have even built vertical evacuation towers because they are so flat and low-lying.

Surprising Spots Most People Miss

- Cape Disappointment: Don't let the name fool you. It’s stunning. It’s where the Columbia River meets the Pacific. The waves here can reach 30 or 40 feet during winter storms.

- Kalaloch’s Tree of Life: On the map, it’s just a spot near the lodge. In person, it’s a Sitka spruce hanging on for dear life across a gully where the ground has eroded beneath it.

- Point Grenville: This is on Quinault land and offers some of the most dramatic views of sea stacks, but you need to check for tribal permits before visiting certain areas.

The coast of Washington state map is a living document. Between the rising sea levels and the constant pounding of the North Pacific, the shoreline you see on paper today won't be the same shoreline your grandkids see. The "Lost Coast" sections are growing as roads wash out and the state decides it's too expensive to rebuild them.

Actionable Steps for Your Coastal Exploration

If you are actually going to head out there, don't just wing it.

- Download Offline Maps: Cell service is basically non-existent once you get north of Moclips. Download your Google Maps areas or use a dedicated GPS app like Gaia GPS.

- Get a Paper Tide Table: You can find these at almost any gas station or bait shop on the coast. Learn how to read them. Remember that the timing for "Low Tide" changes as you move north from the Columbia River.

- Check the "WSDOT" App: Check for road closures on Highway 101. Landslides are incredibly common in the winter and spring, often cutting off access to the northern peninsula for days.

- Identify Public vs. Private Land: Large chunks of the coast are Tribal Reservations (Makah, Quileute, Hoh, Quinault). Respect their borders. Some beaches require a specific tribal permit to visit or park.

- Pack for "The Big 3": Rain, wind, and cold. Even in July, the coast can be 55 degrees and foggy while Seattle is 90 degrees and sunny.

The Washington coast isn't a place you visit to "tan." It's a place you visit to feel small. The map is just your starting point to get lost in the right direction.