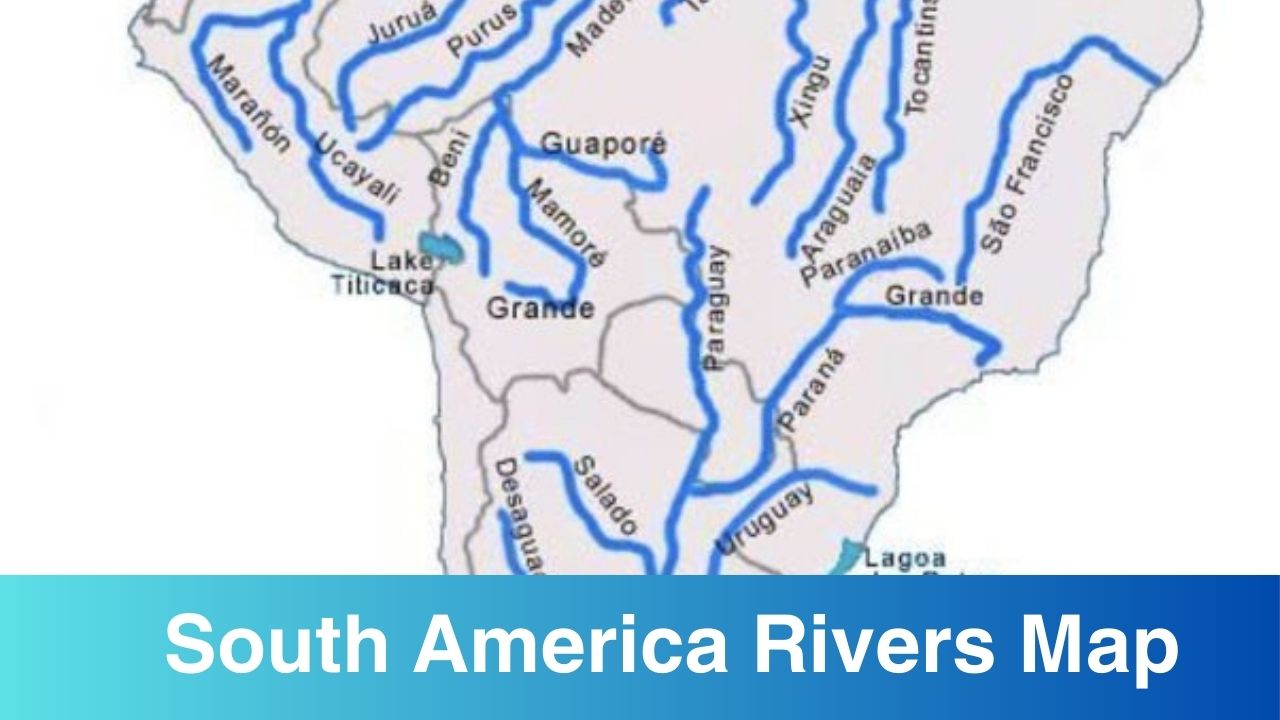

Look at a map. You see blue lines, right? Some are thick, some are spindly, like a nervous system etched across a continent. If you're staring at a rivers of South America map, you aren't just looking at water. You’re looking at the literal highways of history, ecology, and survival. Most people glance at the Amazon and move on. That’s a mistake. Honestly, the way we represent these waterways on paper is kinda misleading because it misses the sheer, violent scale of what's actually happening on the ground.

South America is a tilted continent. It’s lopsided. The Andes mountains run down the west coast like a jagged spine, forcing almost all the major water systems to flow east toward the Atlantic. It's a massive drainage project designed by geography.

The Amazon isn't just a river—it's an ocean in disguise

When you find the Amazon on a rivers of South America map, it looks like a single vein. In reality, it's more of a pulse. This thing carries more water than the next seven largest rivers combined. Think about that for a second. It’s hard to wrap your head around. If you stood at the mouth in Brazil, you couldn't see the other side. It’s basically a sea that happens to be moving in one direction.

The Amazon Basin is fed by thousands of tributaries. Some of these, like the Madeira or the Rio Negro, are massive rivers in their own right, larger than most European systems. The Rio Negro is particularly wild. It’s "black water," stained the color of strong tea by decaying vegetation. When it meets the pale, sandy Solimões River near Manaus, they don't mix right away. They run side-by-side in the same channel—black and tan—for miles. Scientists call this the "Meeting of Waters." It happens because of differences in temperature, speed, and water density.

You’ve probably heard people call the Amazon the "lungs of the planet." That's actually a bit of a myth. Most of the oxygen it produces is consumed by the forest itself. Its real value is as a giant air conditioner and a biological library. The sheer volume of water moving through this system regulates the climate of the entire Southern Hemisphere. If the Amazon stops flowing correctly, farmers in Argentina start losing crops. Everything is connected.

💡 You might also like: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

Why the Orinoco and Paraguay systems matter more than you think

If you slide your eyes north on your rivers of South America map, you’ll hit the Orinoco. It's mostly in Venezuela and Colombia. This river is famous for the Casiquiare canal. Geography geeks love this because it's a natural "fork" that connects the Orinoco river system with the Amazon system. It’s one of the only places on Earth where two major river basins are naturally linked. It’s like a back door between two giant mansions.

Then you have the Río de la Plata system.

It’s way down south. This isn't just one river, but the combined force of the Paraná and Uruguay rivers. This is where Buenos Aires and Montevideo sit. This estuary is vital for trade, but it's also incredibly shallow and silt-heavy. Navigation here is a constant battle against the mud.

- The Paraná is the second longest river in South America.

- It feeds the Itaipu Dam, which provides a staggering amount of electricity to Paraguay and Brazil.

- Unlike the Amazon, which is mostly wilderness, the Paraná is a working river, heavily dammed and industrial.

The Pantanal is another spot you need to know. It's the world's largest tropical wetland. It’s fed by the Paraguay River. During the wet season, the river overflows its banks, and the entire region turns into an inland sea. It’s not a "river" in the traditional sense of a moving line on a map; it's a slow-motion flood that supports the highest concentration of wildlife in South America. If you want to see jaguars, you go here, not the dense Amazon.

📖 Related: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

The hidden complexity of the Magdalena and the São Francisco

Most people skip the Magdalena River in Colombia. Big mistake. This river was the primary highway for the Spanish to reach the interior of the continent. It’s the soul of Colombian culture. Because the Andes split into three distinct ranges in Colombia, the Magdalena flows north through a massive valley between them. It’s a vertical world.

Then there’s the São Francisco in Brazil. It’s often called the "River of National Unity." Why? Because it connects the diverse regions of Brazil, flowing through the arid "Sertão" backlands. It’s the only large river in Brazil that doesn't disappear during the dry season in this desert-like area. It’s literally the difference between life and death for millions of people. There has been a huge, controversial project recently to divert its water to even drier areas. People are fighting over this water. It’s messy, political, and deeply human.

Mapping the threats: It isn't just about lines on paper

When you look at a rivers of South America map today, you aren't seeing the dams. You aren't seeing the mercury from illegal gold mining. In the Tapajós river basin, indigenous communities are dealing with toxic levels of mercury in their fish. The gold miners use mercury to separate gold from sediment, and it washes right into the food chain.

Climate change is also messing with the rhythm. The "rivers in the sky"—massive plumes of water vapor that travel from the Amazon to the south—are weakening. This leads to historic droughts in places like São Paulo. A map shows you where the water is supposed to be, but it doesn't show you that some of these rivers are reaching record-low levels. In 2023 and 2024, the Rio Negro hit its lowest levels in over a century. Boats were stranded. Entire villages were cut off from the world.

👉 See also: Why the Map of Colorado USA Is Way More Complicated Than a Simple Rectangle

How to actually use this information

If you’re planning to travel or study these regions, don't just trust a static image. You need to understand the seasonality.

- Check the Flood Pulse: In the Amazon, "high water" season can raise the river level by 30 to 40 feet. The forest floor disappears. You boat through the canopy of the trees.

- Watch the Sediments: Rivers are categorized by color. White water (like the Amazon) is nutrient-rich and muddy. Black water (like the Negro) is acidic and has fewer mosquitoes. Clear water (like the Tapajós) comes from the ancient highlands.

- Respect the Rapids: Many South American rivers are interrupted by "cachoeiras" or waterfalls. The Iguaçu Falls on the border of Brazil and Argentina is the most famous example. You can't just sail from the ocean to the mountains; geography won't let you.

The rivers of South America map is a living thing. It's shifting. It’s drying in some places and flooding in others. To truly understand it, you have to look past the blue ink and see the power plant, the highway, the sacred site, and the ecological engine that it really is.

To get a better grip on this, your next move should be looking into "Relief Maps" of the continent. Layering a river map over a topographical relief map explains why the Amazon is so wide and why the Pacific coast has almost no major rivers. Compare the seasonal water levels of the Negro and Solimões to understand when navigation is actually possible for cargo or travel. Finally, track the deforestation rates along the "Arc of Deforestation" in the southern Amazon, as this directly impacts how much rain these rivers receive. Understanding the water is the only way to truly understand South America.