Utah is weird. I mean that in the best way possible, but if you’re staring at a map of US Utah, you’re looking at a jigsaw puzzle designed by someone who loved right angles but hated consistent terrain. Most people see that big, notched rectangle in the West and think "red rocks" or "Salt Lake City," and yeah, those are there. But a map doesn't always convey the sheer verticality of the place. You’ve got the Great Basin to the west, the Colorado Plateau to the southeast, and the Rocky Mountains basically slamming into the middle of it all. It’s a topographical car crash that created some of the most surreal landscapes on the planet.

Honestly, looking at a flat map can be deceiving. You see a road like Scenic Byway 12 and think, "Oh, that’s just a short drive between two parks." Then you get there. Suddenly, you're on the "Hogsback," a strip of asphalt with thousand-foot drops on both sides and no guardrails. Maps tell you where things are; they don't always tell you how they feel.

The Great Divide: Deciphering the Map of US Utah

If you split the state down the middle vertically, you get two different worlds. The western half is dominated by the Basin and Range province. This is where you find the Bonneville Salt Flats. It’s flat. Like, "see the curvature of the earth" flat. If you’re driving I-80 toward Nevada, the map looks like a straight line because it is. But then you look at the eastern and southern sections. This is the Colorado Plateau. It’s a massive uplifted block of earth that’s been gnawed on by the Colorado River and its tributaries for millions of years.

Why the "Wasatch Front" Dominates Everything

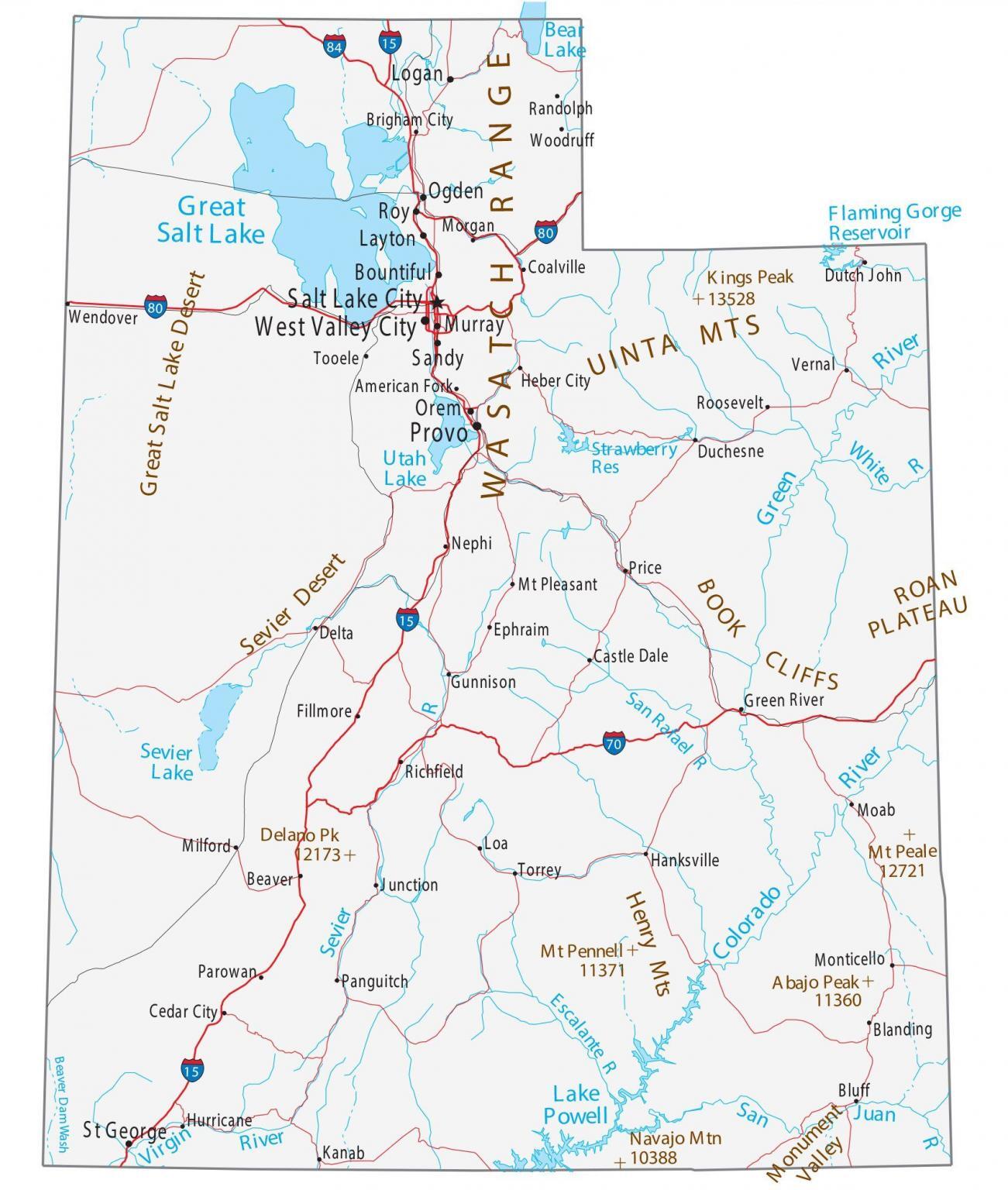

Look at a population density overlay of any map of US Utah. You’ll notice a tiny, cramped strip of development running from Brigham City down to Santaquin. That’s the Wasatch Front. Roughly 80% of Utahns live here. Why? Because the mountains—the Wasatch Range—act as a giant vertical gutter. They catch the snow, the snow melts, and the water runs down into the valleys. Without those mountains, Salt Lake City would just be a very salty, very dry version of nowhere.

It’s a strange juxtaposition. You can be in a high-tech boardroom in Silicon Slopes (Lehi) and, within twenty minutes, be at a trailhead where there is zero cell service and a non-zero chance of encountering a mountain lion. The map shows proximity, but the elevation creates a wall.

💡 You might also like: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

The Five-Park Problem

Everyone wants to see the "Mighty 5." Zion, Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, Arches, and Canyonlands. On a map of US Utah, they look like a neat little constellation in the bottom half of the state.

- Zion is the heavy hitter. It’s at the bottom left. People think they can "do" Zion in a morning, but the map doesn't show the shuttle lines or the fact that the canyon is so narrow you spend half your time looking straight up.

- Bryce Canyon isn't actually a canyon. It’s a series of giant natural amphitheaters. It’s also much higher in elevation than Zion—about 8,000 to 9,000 feet. If you go in May, Zion might be 85 degrees while Bryce still has snow on the hoodoos.

- Capitol Reef is the one everyone skips. It sits right on the Waterpocket Fold, a 100-mile "wrinkle" in the earth's crust.

- Arches and Canyonlands are neighbors near Moab. Arches is the "greatest hits" album—short walks, famous sights. Canyonlands is the experimental double-LP—vast, rugged, and intimidating.

Most travelers make the mistake of trying to hit all five in a week. Don't. You'll spend more time looking at the dashboard than the dirt. Utah roads aren't always fast. A "line" on a map in San Juan County might turn out to be a washboard dirt road that limits you to 10 miles per hour.

The Water Paradox

Water defines Utah. It’s the second-driest state in the union, yet it’s home to the Great Salt Lake—the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere. If you look at an old map of US Utah from the 1980s versus one from 2026, the lake looks terrifyingly different. It’s shrinking. This isn't just an environmental sob story; it’s a geographical crisis. As the water recedes, the exposed lakebed releases arsenic-laden dust.

Then you have Lake Powell on the Arizona border. It’s a man-made reservoir in a place where water arguably shouldn't be stored. The "bathtub ring" on the canyon walls shows exactly how much the climate has shifted. When you're navigating these areas, the map is a snapshot in time. What looks like a boat ramp on your GPS might be a mile away from the actual water line today.

📖 Related: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

The High Uintas: Utah’s Best Kept Secret

While everyone is fighting for parking spots in Zion, the northern part of the state has the Uinta Mountains. These are weird. They are one of the few mountain ranges in North America that run east-to-west instead of north-to-south.

They are remote. There are peaks over 13,000 feet, including Kings Peak, the highest point in the state. On a map of US Utah, this area looks like a big green blob of national forest. In reality, it’s a land of a thousand lakes and alpine tundra. It’s where locals go when they want to forget that tourists exist.

Beyond the Red Rocks: The West Desert

If you want to feel truly small, go to the West Desert. It’s the part of the map that looks empty. It basically is. Between Delta and the Nevada border, there is a whole lot of nothing—and that’s the point. This is where the Pony Express used to ride. It’s where you’ll find the Topaz Internment Camp site, a somber reminder of WWII history that rarely makes the "scenic" maps.

The roads here are long. If your car breaks down, you're in for a very long walk. But the stars? You haven't seen the Milky Way until you've seen it from the middle of the Great Basin. The lack of light pollution makes this "empty" space on the map one of the most valuable resources for astronomers.

👉 See also: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

Practical Navigation: Things a Map Won't Tell You

- Fuel is a luxury. In places like the San Rafael Swell or the road to Needles District in Canyonlands, you can go 50 to 70 miles without a gas station. If the map shows a town, check if it actually has a pump. Sometimes "town" means three houses and a closed general store.

- The "Mormon Grid." Most Utah cities are laid out on a very specific grid system based on the Salt Lake Meridian. Addresses look like "100 South 200 West." It sounds confusing, but it’s actually the most logical navigation system ever devised once you get the hang of it. You always know exactly how many blocks you are from the city center.

- Flash Floods. A blue line on a map might be a dry wash 360 days a year. On the other 5 days, it’s a wall of debris-filled water that can crush a truck. Never, ever camp in a wash, even if the sky is clear where you are. Rain 20 miles away can trigger a flood in your "dry" canyon.

- Public Lands. Utah has a massive amount of BLM (Bureau of Land Management) and Forest Service land. This means you can often camp for free (dispersed camping), but you won't find toilets or water. The map colors (usually yellow for BLM, green for Forest Service) are your best friend for finding these spots.

The Cultural Map

You can't talk about Utah's geography without mentioning the cultural footprint of the LDS Church. You see it in the architecture—the tabernacles and temples that anchor almost every small town. You see it in the wide streets of Salt Lake City, supposedly designed so a wagon team could turn around without "recourse to profanity."

But there’s also the Indigenous map. The Navajo Nation, the Ute, the Paiute, and the Shoshone were here long before the straight lines of the state border were drawn. Places like Bears Ears National Monument are at the center of a massive tug-of-war between federal protection, state rights, and tribal sovereignty. When you look at a map of US Utah, you’re looking at contested ground.

Navigating the Future of the Beehive State

Utah is growing fast. The "Silicon Slopes" tech boom has turned the area between Salt Lake and Provo into a mini-metropolis. This growth is straining the very things people move here for: the air quality (inversion layers in winter are no joke) and the water.

If you're planning a trip or looking to move, don't just trust a digital map. Get a physical gazetteer. Look at the contour lines. Respect the fact that the desert wants to dehydrate you and the mountains want to snow you in. Utah is a place of extremes. It's beautiful, harsh, and complicated.

Next Steps for Your Utah Expedition:

- Check the "Snowpack" Reports: Before heading to the mountains or the desert in spring, look at the SNOTEL data. A high snowpack means the rivers will be dangerous and the mountain passes might be closed well into June.

- Download Offline Maps: Cell service in the Southern Utah canyons is non-existent. Use apps like Gaia GPS or OnX Backcountry and download the layers for the specific quadrangle you're visiting.

- Validate Water Sources: If you are backpacking, don't trust a map that says "spring." In the desert, springs dry up. Contact the local Ranger Station (like the Interagency Office in Kanab) for real-time water reports.

- Permit Planning: Most iconic spots (Angels Landing, The Wave, Coyote Gulches) now require permits months in advance or through daily lotteries. Your map gets you to the trailhead, but your permit gets you on the trail.