Texas is big. You know that. But when you look at a map of gulf coast of texas, you start to realize that "big" doesn't even begin to cover the 367 miles of coastline stretching from the Sabine River down to the Rio Grande. It’s a jagged, shifting, and surprisingly complex ecosystem that most people simplify into "the beach."

It isn't just one long strip of sand.

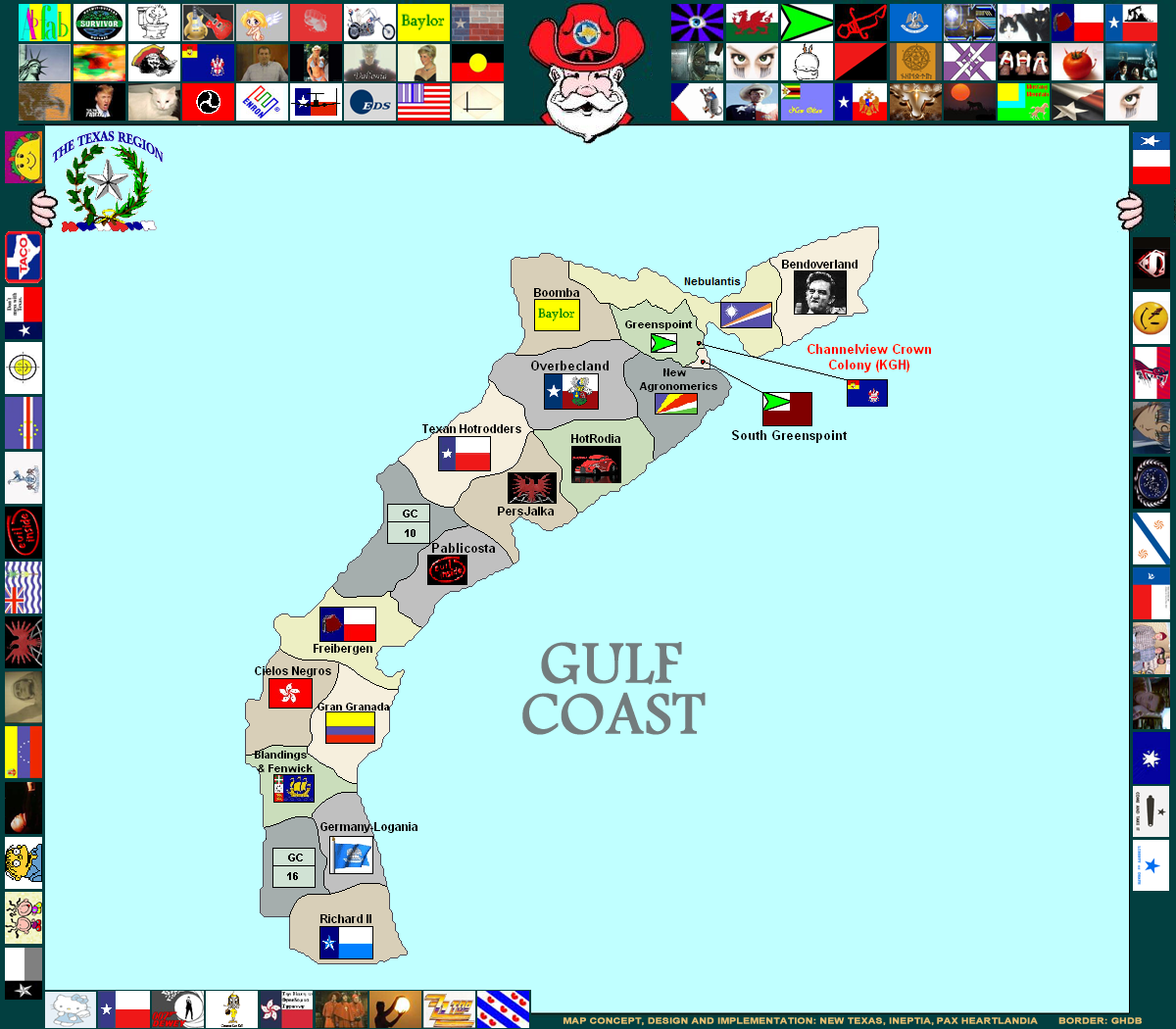

If you're looking at a map right now, you’ll see a massive network of barrier islands, peninsulas, and shallow bays. This isn't just geography; it's a defense mechanism. These islands, like Galveston and Padre, take the brunt of the Gulf of Mexico’s moods so the mainland doesn’t have to. Honestly, if you just head to the coast without understanding how these segments differ, you’re basically flipping a coin on what kind of experience you’re going to get. The upper coast near Louisiana feels like a swampy, industrial extension of the bayou, while the far south near Brownsville is a clear-water tropical escape.

The Upper Coast: Marshes, Industry, and Hidden Refuges

Look at the top right of your map of gulf coast of texas. This is the Upper Coast. It’s dominated by the Houston-Galveston metroplex, but geography-wise, it’s defined by the Chenier Plain.

Jefferson, Chambers, and Galveston counties make up this stretch. Here, the water is often tea-colored. That’s not because it’s "dirty," which is a common misconception, but because of the massive amount of freshwater runoff and silt coming from the Trinity and Sabine rivers. It’s nutrient-rich. It’s why the fishing here is world-class even if the water isn't turquoise.

Galveston Island is the anchor here. If you trace the line of the seawall on a map, you’re looking at a 10-mile long feat of engineering built after the 1900 Storm. But just a bit further northeast lies the Bolivar Peninsula. You have to take a ferry to get there. It’s quieter. It’s where the locals go when Galveston gets too crowded. Then there’s Sea Rim State Park. It’s where the marsh literally meets the surf. You can stand with one foot in a salt marsh and the other in the Gulf. It’s eerie and beautiful.

The industry is unavoidable here too.

🔗 Read more: Why Presidio La Bahia Goliad Is The Most Intense History Trip In Texas

You'll see huge tankers lining up at the Port of Houston or Port Arthur. On a map, these deep-water channels look like scars cut into the coastline. They are the economic engine of Texas, but they also create a weird juxtaposition where you might be birdwatching at High Island—one of the best migratory bird spots in North America—while seeing an oil rig on the horizon.

The Middle Coast: The Great Bend and Secret Bays

Moving south, the map of gulf coast of texas starts to curve. This is the "Coastal Bend." It centers around Corpus Christi.

This area is different. The barrier islands get longer and narrower. Matagorda Island and St. Joseph Island are largely undeveloped. If you want to see what Texas looked like 500 years ago, this is where you look. There are no bridges to these places. You need a boat.

The water starts to clear up here.

The Port Aransas Dynamic

"Port A" is the heartbeat of the middle coast. On a map, it sits at the tip of Mustang Island. It’s a golf-cart town. To the north is the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. This is the winter home of the Whooping Crane. In the 1940s, there were only about 15 of these birds left in existence. Today, thanks to the protection of this specific stretch of Texas shoreline, there are hundreds. It’s a massive conservation success story that happened right in these marshes.

Corpus Christi and the Bay

Corpus Christi is tucked behind Mustang Island and Padre Island. It sits on a high bluff, which is rare for the Texas coast. If you look at the bathymetry—the underwater map—of Corpus Christi Bay, it’s shallow. Most of the Texas bays are only about 4 to 12 feet deep. This is why the wind kicks up chop so fast. It’s also why it’s a mecca for windsurfers and kiteboarders. Bird Island Basin, located within the Padre Island National Seashore, is consistently ranked as one of the best spots in the country for these sports because the water is waist-deep for miles.

💡 You might also like: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

The Lower Coast: Tropical Texas and the Laguna Madre

As you move toward the bottom of the map of gulf coast of texas, things get weird. In a good way.

The Laguna Madre is a "hypersaline" lagoon. There are only a handful of these in the entire world. Because there are so few inlets to the Gulf and very little freshwater inflow, the water is saltier than the ocean. On a map, it looks like a long, thin sliver of blue trapped between the mainland and Padre Island.

This saltiness creates a unique habitat. The seagrass beds here are massive. They support a huge population of Redfish and Spotted Seatrout.

The Longest Barrier Island in the World

Padre Island is the star of the show. It’s about 113 miles long. Most of it is the Padre Island National Seashore (PINS). On a map, you’ll notice a huge gap where there are no roads. This is the "Big Shell" and "Little Shell" beaches. It is primitive. There are no gas stations, no cell service, and no help if you get stuck in the sand. It’s one of the last truly wild places in the lower 48 states.

South Padre: The End of the Road

Finally, you hit South Padre Island (SPI). Don't confuse it with the National Seashore; they are separated by the Mansfield Cut, a man-made channel. SPI is where the water finally turns that Caribbean blue-green. The continental shelf drops off further out, and the influence of the Rio Grande is minimal compared to the rivers up north. It’s a tropical paradise stuck on the end of a Texas highway.

Why the Map Keeps Changing

Texas is losing its coastline. That’s not hyperbole; it’s measurable geography.

📖 Related: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

When you study a map of gulf coast of texas over decades, you see the "retreat." Erosion is a massive issue. Places like Sargent Beach have had to install massive granite revetments just to keep the Gulf from swallowing the Intracoastal Waterway.

The Intracoastal Waterway (GIWW) is another thing you’ll see on any good map. It’s a man-made canal that runs the entire length of the coast. It allows barges to move goods from Brownsville to Florida without ever having to face the open ocean. It’s a vital piece of infrastructure, but it also changed the way water flows in the bays. It’s a constant balancing act between commerce and ecology.

How to Use a Texas Coastal Map for Planning

If you're planning a trip, don't just look at the dots for cities. Look at the "passes."

Bolivar Roads, San Luis Pass, Aransas Pass, Brazos Santiago. These are the openings where the tide rushes in and out. They are dangerous for swimmers but incredible for fishermen. San Luis Pass, at the west end of Galveston Island, is notorious for its treacherous currents. People drown there every year because they don't realize how much water is moving through that narrow gap on the map.

- For Solitude: Look at the Matagorda Peninsula or the Padre Island National Seashore.

- For Biology: Look at the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge or the Laguna Atascosa.

- For Amenities: Stick to Galveston or South Padre Island.

- For Deep Sea Fishing: Look at Freeport or Port O'Connor, where the "deep water" is a shorter boat ride away.

The Texas coast isn't a monolith. It’s a 400-mile transition from Louisiana cypress swamps to Mexican high-desert dunes. Understanding the map of gulf coast of texas is about more than finding a beach; it’s about understanding the delicate geometry of a coastline that is constantly trying to reshape itself.

Next time you look at that map, don't just see a line. See the barrier islands for the shields they are, the bays for the nurseries they provide, and the passes for the gateways they open.

Practical Next Steps for Coastal Navigation

To truly understand this region, your next step should be checking the Texas General Land Office (GLO) website for their "Beach Watch" and "Coastwide Monitoring System" data. This provides real-time updates on water quality and erosion rates that static maps can't show. If you're planning to drive on the beach, download a high-resolution topography map specifically for the Padre Island National Seashore, as the shifting "driving lanes" depend entirely on the current tide cycle and seasonal berm movements. Finally, check the NOAA Nautical Charts for any of the Texas bays to see the actual depths; you'll be surprised to find that much of what looks like "open water" on a standard map is actually only two feet deep, which is crucial info for anyone taking a boat out.