Europe is small. Honestly, when you look at a flat projection, it’s tiny compared to Africa or Asia, but it’s dense. It’s packed. And if you’re looking at a map of Europe with the Alps, you start to see why the continent evolved into such a messy, beautiful patchwork of cultures. That giant white-and-green spine running through the center isn't just a pretty backdrop for postcards from Switzerland. It’s a wall. It’s a bridge. It’s the reason people in Milan don’t speak the same way as people in Zurich, despite being just a few hours apart.

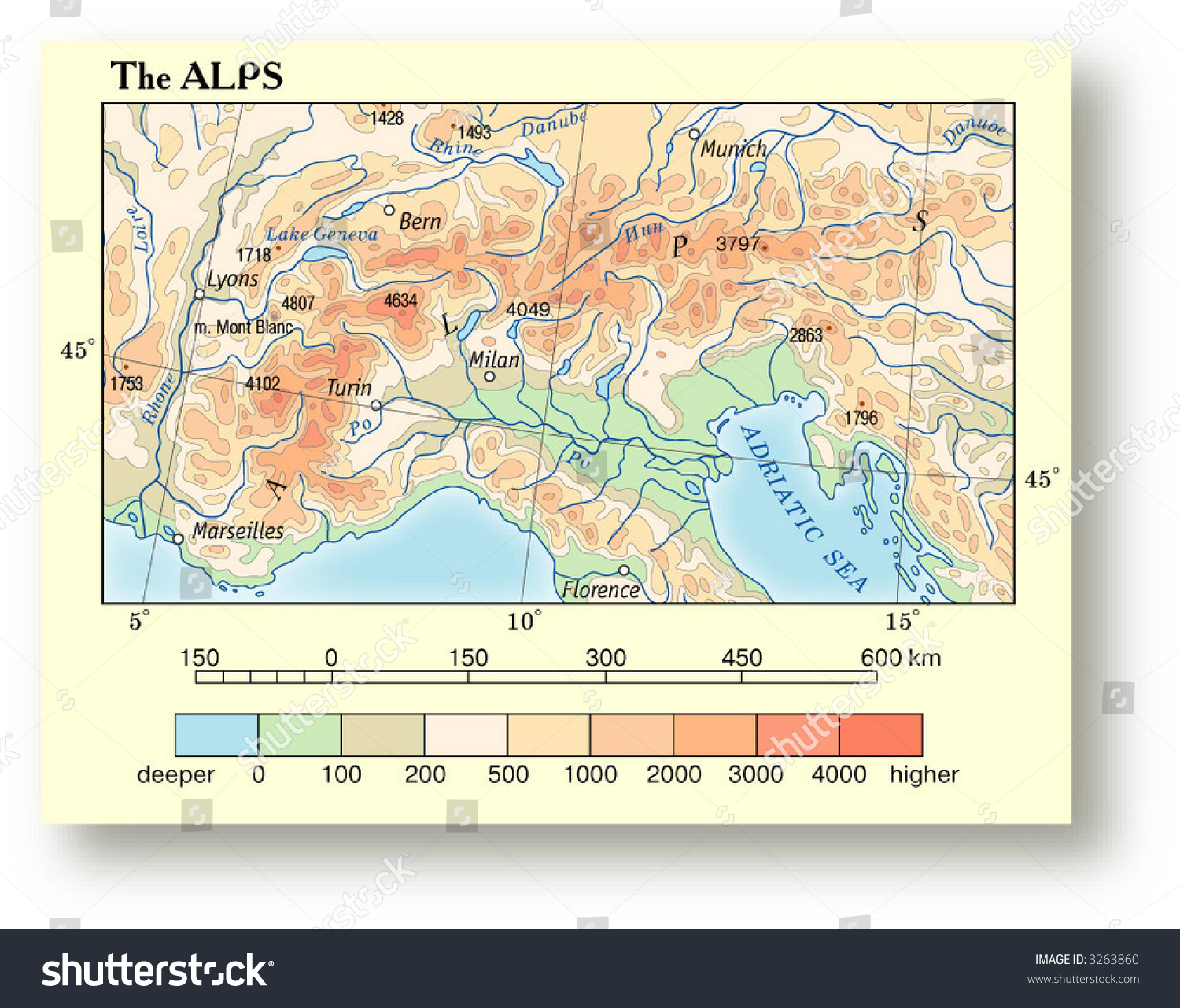

Most people pull up a map and just see mountains. They see a jagged line. But if you really look at the topography, you see the "Great Barrier" of human history. The Alps stretch roughly 750 miles across eight countries. France, Switzerland, Monaco, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, and Slovenia all claim a piece of this rock. When you visualize this on a physical map, you realize the Alps are the "water tower" of Europe. Without that specific elevation, the Rhine, the Rhône, and the Danube wouldn’t exist as we know them. The map is basically a plumbing diagram for an entire civilization.

Why a Map of Europe with the Alps Looks Different Depending on Who Made It

You’d think a mountain is just a mountain, right? Wrong.

If you grab a geological map, the Alps look like a collision. That’s because they are. About 35 million years ago, the African and Eurasian tectonic plates decided to smash into each other. The "Tethys Ocean" disappeared, and the seafloor got pushed into the sky. This is why you can find marine fossils at the top of limestone peaks. When you’re looking at a map of Europe with the Alps, you’re looking at the literal scars of a planetary car crash.

But look at a political map, and the Alps become a headache. Borders in the mountains are weird. They usually follow the "watershed line"—the highest ridges where water flows one way or the other. But glaciers melt. The "Theodul Glacier" near Zermatt has shifted so much that an Italian restaurant, the Rifugio Guide del Cervino, actually ended up partially in Switzerland. This isn't just trivia; it's a legal nightmare for tax authorities and surveyors. A map is a snapshot in time of a landscape that is actively moving.

The North-South Divide

There’s a reason Northern Europe feels "Northern" and Southern Europe feels "Mediterranean."

The Alps block the cold winds from the north and trap the warm air from the south. If you’re looking at a climate-focused map of Europe with the Alps, you’ll see a sharp color shift. To the north, you have the maritime and continental climates—lots of green, lots of rain, gray skies. To the south, the Po Valley in Italy is a different world. The mountains act as a giant climate wall.

It’s not just weather. It’s logistics.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

Historically, crossing the Alps was a death wish. Hannibal tried it with elephants. Napoleon did it with an army. But for the average merchant in the year 1400, a map of the Alps was a list of ways to die. The St. Gotthard Pass, the Brenner Pass, and the Great St. Bernard were the only "doors" in the wall. If you look at a modern map of Europe with the Alps, you’ll see thin lines cutting through the rock—tunnels like the Gotthard Base Tunnel, which is the longest railway tunnel in the world. We spent billions of euros just to ignore the map's natural barriers.

The Highest Peaks and Where to Actually Find Them

Don't let the map fool you into thinking the mountains are evenly distributed.

The "Western Alps" are higher and more rugged. This is where you find Mont Blanc (the "White Mountain"), sitting on the border of France and Italy. It’s 4,807 meters of granite and ice. If you move east, the mountains get lower but wider. The Austrian Alps—the "Eastern Alps"—are where you find the limestone massifs that look like jagged teeth.

- Mont Blanc: The king of the west.

- The Matterhorn: The most iconic shape, even if it’s not the highest.

- Grossglockner: The highest point in Austria, located in the High Tauern range.

- Triglav: The soul of Slovenia and its highest peak.

When you look at a map of Europe with the Alps, notice how the range curves. It’s not a straight line. It’s a crescent moon shape. This curve is what created the specific microclimates of the French Riviera and the Italian Lakes. The mountains wrap around the Gulf of Genoa, protecting the coast from the biting northern "Mistral" winds.

The Vanishing White on the Map

We have to talk about the colors. On most maps, the high Alps are white or light gray to represent perennial snow and glaciers.

That white is shrinking.

Glaciologists like Matthias Huss from ETH Zurich have been tracking this for decades. Since the mid-19th century, Alpine glaciers have lost about half their volume. If you compare a map of Europe with the Alps from 1920 to one from 2024, the "white bits" are significantly smaller. Some glaciers, like the Pasterze in Austria, are retreating so fast that maps have to be updated every few years. It’s a sobering reality. The "Water Tower" is leaking.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

The Cultural Map: Who Lives in the Folds?

Mountains isolate people.

Isolation creates unique cultures.

If you overlay a linguistic map on top of a map of Europe with the Alps, you see something fascinating. You see Romansh in Switzerland—a language that sounds like Latin mixed with a mountain echo. You see Ladin in the Italian Dolomites. You see the Walser people, who migrated across the high ridges centuries ago, bringing their specific architecture and dialects with them.

The Alps aren't just a place people visit to ski; they are a home to 14 million people.

The "Alpine Convention," an international treaty, treats this entire mountain range as a single unit. It’s an acknowledgment that the people living in the mountains of France have more in common with the people in the mountains of Slovenia than they do with people living in Paris or Ljubljana. They share the same challenges: avalanches, tourism management, and the sheer difficulty of building a road that doesn't wash away in a landslide.

Using a Map of Europe with the Alps for Travel Planning

So, you’re looking at the map and trying to plan a trip. Don't just look at the distance between cities.

A 50-mile drive on the flat plains of Germany takes 45 minutes. A 50-mile drive in the heart of the Alps might take three hours. The map is deceptive because it doesn't show the verticality. You’re going up and down, not just across.

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

If you want the "classic" Alpine experience, you look at the "Bernese Oberland" in Switzerland. On the map, it’s a cluster of peaks south of Bern. If you want something more dramatic and vertical, you look at the "Dolomites" in Northeastern Italy. These aren't the same kind of rock. The Dolomites are ancient coral reefs. They turn pink at sunset.

Essential Map Markers for Travelers

- Chamonix, France: The base for Mont Blanc.

- Interlaken, Switzerland: The gateway to the Eiger and Jungfrau.

- Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy: The heart of the Dolomites.

- Innsbruck, Austria: A city literally surrounded by "walls" of rock.

- Bled, Slovenia: Where the Alps meet the Julian forest.

The Practical Science of the Map

Cartographers use "shaded relief" to make the Alps pop on a map. Without it, the mountains just look like a brown blob. This technique uses light and shadow to simulate how the sun hits the ridges. When you see a map that looks 3D, that's often the "Swiss Style" of cartography, pioneered by people like Eduard Imhof. They turned map-making into an art form, ensuring that hikers wouldn't just see a mountain, but would understand its shape, its steepness, and its dangers.

The Alps are also the most densely mapped mountains in the world. Because of the population density and the proximity to major European cities, every square inch has been surveyed. We have "LIDAR" maps that can see through the trees to find Roman ruins hidden in the Alpine foothills.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Map Search

If you’re hunting for the perfect map of Europe with the Alps for your wall or your next trip, keep these things in mind:

- Scale Matters: A map of the whole continent will make the Alps look small. Look for a "Regional Map of the Alpine Arc" to see the detail of the valleys.

- Check the Date: If you're using a map for hiking, anything older than five years might be wrong about glacier boundaries or even certain trailheads.

- Topography vs. Satellite: Satellite images are beautiful, but topographic maps (with contour lines) are what you actually need to understand the terrain.

- The "Pass" Perspective: Look for the passes. If you’re driving, the map of the tunnels (like the Fréjus or Mont Blanc) is more important than the map of the peaks.

The Alps are the heart of Europe. They are the reason the continent's history took the path it did. They forced people to trade, to fight, and eventually, to build some of the most impressive engineering marvels on Earth. Next time you look at that map, don't just see a mountain range. See the spine that holds the whole place together.

To get the most out of your Alpine exploration, start by identifying the four major gateways: Geneva, Zurich, Munich, and Milan. From these points, the map opens up, revealing the hidden valleys and high-altitude passes that have defined European life for millennia.

Next Steps for Your Alpine Journey

- Select your "Alpine Style": Decide if you prefer the high-glacier peaks of the Western Alps (France/Switzerland) or the jagged limestone of the Eastern Alps (Italy/Austria).

- Download Offline Topographic Maps: Use apps like Gaia GPS or Outdooractive, as cell service is notoriously spotty once you drop into deep glacial valleys.

- Cross-Reference Rail Maps: If you aren't driving, look for the "Bernina Express" or "Glacier Express" routes on your map; these are the most scenic ways to see the topography without a car.

- Monitor the Snow Line: Use real-time satellite maps (like those from Copernicus) to see current snow cover before planning a shoulder-season hike in late spring or autumn.

The map is just the beginning; the real scale of the Alps is something you only feel once you're standing in their shadow.