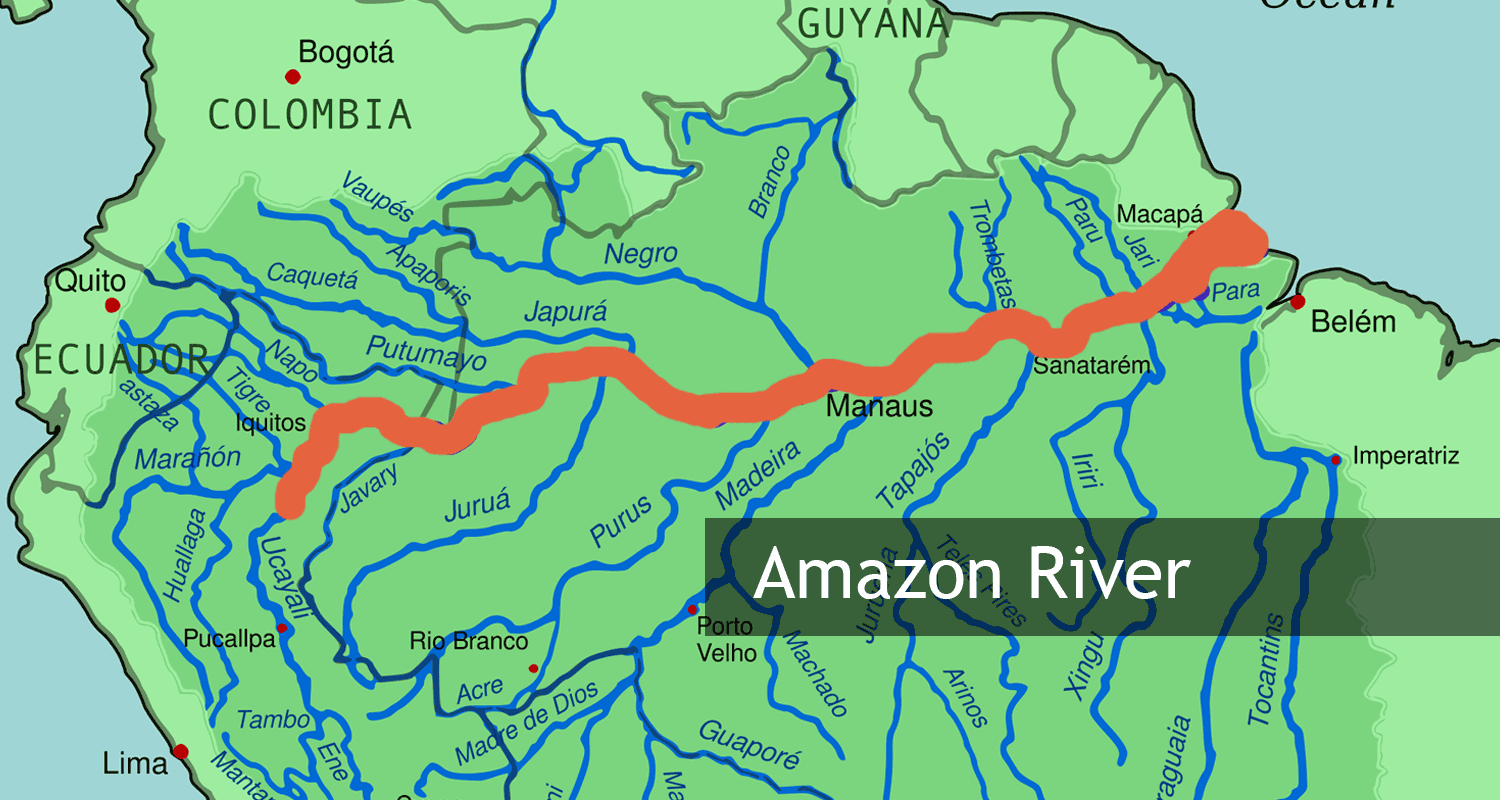

Look at a map Amazon River South America for more than five seconds and you’ll start to see it. It isn't just a blue line. It’s a massive, sprawling nervous system that keeps an entire continent breathing. People usually think they know the Amazon. They think "big jungle" and "lots of water." But honestly, most maps don’t even begin to show the sheer, chaotic scale of what’s happening on the ground in Brazil, Peru, and Colombia.

It's huge. Like, scary huge.

If you poured the Amazon’s water into the Nile, the Yangtze, and the Mississippi all at once, you’d still have room to spare. When you trace that line from the Andes mountains all the way to the Atlantic, you aren't just looking at a river. You're looking at 20% of the world's fresh water discharge.

The Disappearing Act of the Source

Where does it actually start? That's a fight geographers have been having for decades. For a long time, everyone pointed at Mount Mismi in Peru. They’d show you a tiny glacial stream and say, "There it is." But then, around 2014, researchers like James "Rocky" Contos used GPS tracking and satellite data to argue that the Mantaro River is actually the true source.

Why does this matter for your map Amazon River South America? Because it changes the length. If the Mantaro is the start, the river is about 47 to 50 miles longer than we thought. It makes the "Is it longer than the Nile?" debate even messier. Most modern digital maps now try to compromise, but if you're looking at an old school paper map, it's probably wrong about the headwaters.

🔗 Read more: Madison WI to Denver: How to Actually Pull Off the Trip Without Losing Your Mind

The river doesn't just flow; it pulses. During the wet season, the water level rises by over 30 feet. Imagine a three-story building. Now imagine the river rising until it hits the roof. Maps don't usually show the Varzea—the flooded forests. For half the year, thousands of square miles that look like "land" on a map are actually navigable by boat. You can literally paddle through the canopy of the trees.

Understanding the Map Amazon River South America Beyond the Blue Line

If you’re trying to navigate or even just visualize the region, you have to understand the "colors." This is something a standard map Amazon River South America rarely captures. Scientists and locals divide the basin into three distinct types of water:

- Blackwater: Think of the Rio Negro. It looks like black coffee because of the decaying leaf matter (tannins). It’s acidic and, weirdly enough, has very few mosquitoes.

- Whitewater: This isn't actually white. It’s a muddy, milky brown. The Solimões is the big one here. It’s loaded with sediment from the Andes.

- Clearwater: These rivers, like the Tapajós, run over ancient bedrock. They are transparent and beautiful.

The most famous spot on the map is the "Meeting of the Waters" near Manaus. This is where the black Rio Negro and the sandy Solimões hit each other. They don't mix. Not for miles. Because of differences in temperature, speed, and density, they run side-by-side like a two-tone highway. You can see it from space. If you're looking at a satellite view on a digital map, it’s a stark, unmistakable line.

The Impact of Infrastructure

Modern maps are starting to show a darker side of the basin. Roads. Specifically, the BR-163 and the Trans-Amazonian Highway.

💡 You might also like: Food in Kerala India: What Most People Get Wrong About God's Own Kitchen

On a map, these look like progress. On the ground, they look like "fishbone" patterns of deforestation. When a road goes in, people follow. They clear land for cattle and soy. If you look at a time-lapse map of the Amazon from 1980 to 2026, the green doesn't just fade; it gets eaten away in straight lines.

Why Your Map Is Probably Lying to You

Most maps use the Mercator projection. You know the one. It makes Greenland look the size of Africa. Because the Amazon sits right on the Equator, it actually looks smaller on these maps than it really is.

The Amazon Basin covers about 2.7 million square miles. That is nearly the size of the contiguous United States. When you look at a map Amazon River South America, your brain struggles to register that the distance from the Peruvian Andes to the Brazilian coast is roughly the same as driving from New York City to Los Angeles.

There are no bridges. None. Zero.

📖 Related: Taking the Ferry to Williamsburg Brooklyn: What Most People Get Wrong

Across the entire main stem of the river, there isn't a single bridge for cars. The river is too wide, the banks are too soft, and the seasonal flooding is too violent to make a bridge feasible or even necessary. Most people move by hammock boat—large, multi-story ferries where you tie up your bed and swing for three days while the jungle slides by.

The "Hidden" Cities

We tend to think of the Amazon as an empty wilderness. Maps often reinforce this by showing vast green spaces with only a few dots. But look closer at a high-resolution map Amazon River South America.

- Manaus: A city of over 2 million people in the middle of the jungle. It has an opera house with Italian marble.

- Iquitos: The largest city in the world that cannot be reached by road. You fly in, or you boat in. That's it.

- Belém: The gateway at the mouth of the river, where the Amazon meets the Atlantic with such force that the ocean stays fresh for miles offshore.

Navigating the Basin: Practical Reality

If you’re planning to actually visit or study the area, you need more than a topographical map. You need a bathymetric one. The river depth varies wildly. In some spots, it’s 300 feet deep—deep enough to submerge the Statue of Liberty. In others, shifting sandbars can ground a massive cargo ship in seconds.

The river is alive. It meanders. It creates "oxbow lakes" where the river used to flow but got cut off. On a map, these look like crescent moons scattered across the landscape. They are hotspots for biodiversity, home to giant otters and black caimans.

Actionable Insights for Using an Amazon Map

Stop treating the map as a static image. It’s a snapshot of a moving target. If you want to understand the region, do this:

- Layer Your View: Use Google Earth’s historical imagery tool. Compare the "Meeting of the Waters" or the outskirts of Porto Velho from 2000 to now. The change is jarring.

- Check the Season: If you are traveling, look at the "flooded forest" zones. A map that shows a trail in October might show a lake in May.

- Look for Indigenous Territories: Modern maps are finally starting to include the boundaries of protected indigenous lands. These are often the only parts of the map that remain deep, solid green.

- Verify the Scale: Always use the scale bar. Distances in the Amazon are deceptive because travel is measured in days, not miles. A "short" trip on the map might be a 12-hour boat ride.

The Amazon isn't just a place on a map. It’s a hydrological engine. It creates its own weather—the "flying rivers" of vapor that provide rain for the rest of South America. When you look at that blue line, remember that it's carrying the lifeblood of a continent. It is beautiful, it is dangerous, and it is way bigger than you think.