You’ve seen the photos. Golden masks, neon-blue hieroglyphs, and tourists sweating under a relentless Egyptian sun. But if you actually look at a standard map of the Valley of the Kings, you’re getting a flattened, simplified version of one of the most complex architectural puzzles on the planet. It’s not just a cemetery. It’s a 3D honeycomb.

Most people think of the Valley—Biban el-Moluk—as a flat piece of desert with some holes in it. Honestly, it’s more like a multi-story parking garage designed by someone obsessed with the afterlife. The Theban Hills are made of limestone, and over five centuries, New Kingdom pharaohs carved more than 60 tombs into this rock. They didn't just go straight back; they went down, they veered left to avoid hitting a neighbor's tomb, and sometimes they just stopped mid-swing when the king died too early.

If you’re planning to visit Luxor or just trying to wrap your head around how they fit all those "houses of eternity" into one wadi, you need to understand that a 2D map is just the starting point.

The Layout They Don’t Tell You About

The Valley is split into two wings: the East Valley and the West Valley. Most tourists never even see the West Valley, which is a shame, but that’s where the tomb of Amenhotep III sits in quiet isolation. The East Valley is the "main" one. This is where you find the heavy hitters like Ramses VI, Seti I, and that famous boy king everyone talks about.

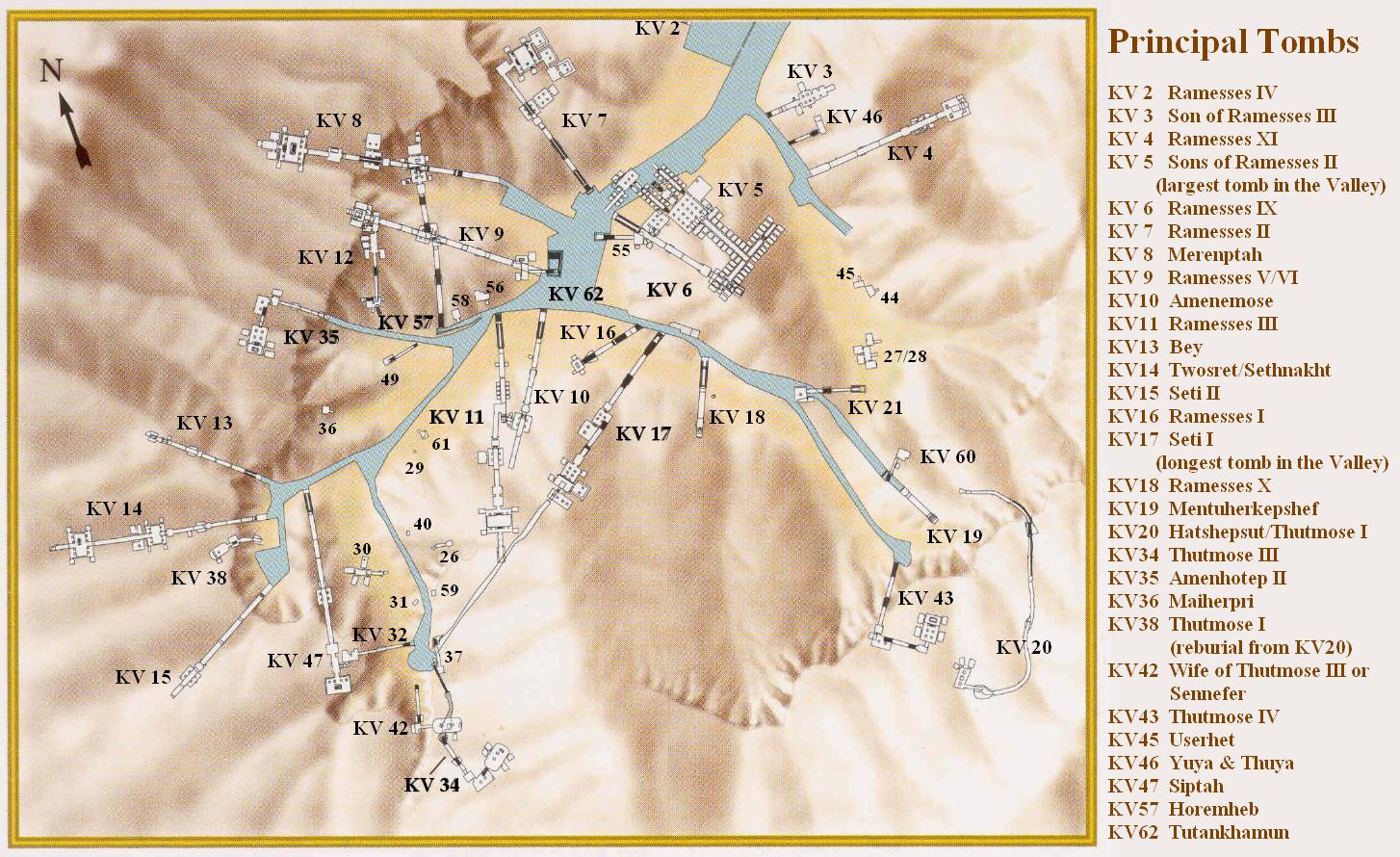

When you look at a map of the Valley of the Kings, you’ll notice the tombs are labeled "KV" followed by a number. KV stands for Kings' Valley. The numbering isn't chronological. It's not like the first king got KV1 and the last got KV62. Nope. The numbers were assigned by Giovanni Battista Belzoni and later explorers based on the order they were "officially" found or recorded. KV1 is actually Ramses VII, a later king, but it’s near the entrance, so it got the top spot on the list.

It’s messy.

👉 See also: Jannah Burj Al Sarab Hotel: What You Actually Get for the Price

The real challenge for any cartographer is the depth. Take the tomb of Seti I (KV17). It’s the longest and deepest in the valley. If you drew it on a flat map, it would look like a long line. In reality, it plunges 450 feet into the earth. It has stairways that drop off into nothingness, meant to fool tomb robbers or perhaps symbolize the journey into the Duat. You’ve got corridors that suddenly shift 90 degrees. Why? Sometimes it was a religious shift in architectural style. Other times, the builders literally hit a vein of bad rock and had to pivot to keep the roof from caving in.

Avoiding a Mid-Air Collision (Underground)

Think about the logistical nightmare of digging these things. The royal architects, the "Scribes of the Tomb" from the village of Deir el-Medina, didn't have ground-penetrating radar. They had copper chisels and oil lamps.

There’s a famous instance involving the tombs of Ramses III (KV11) and Amenmesse (KV10). The workers digging KV11 were moving along quite nicely until—crunch—they broke right through the ceiling of KV10. Imagine the awkward conversation at the lunch break. "Hey, sorry, we just dropped a bunch of rubble into your grandfather's burial chamber." Because of this, the map of KV11 has a weird "step-up" where they had to shift the axis of the tomb to avoid the existing structure.

This is why modern mapping projects, like the Theban Mapping Project led by Dr. Kent Weeks, are so vital. They use 3D modeling to show how these tombs weave over and under each other. Without these sophisticated maps, we wouldn't realize that some tombs are literally inches apart in the bedrock.

The Tutankhamun "Mistake"

Every map of the Valley of the Kings has a tiny little speck near the center labeled KV62. That’s Tutankhamun. In the grand scheme of the Valley, his tomb is a closet. It’s cramped. It’s undecorated in the first few rooms. It was likely a noble's tomb that was hijacked because the king died at 19 and his "real" tomb wasn't ready.

✨ Don't miss: City Map of Christchurch New Zealand: What Most People Get Wrong

But look at where it is on the map. It’s tucked right under the entrance to the massive tomb of Ramses VI. This is the only reason Howard Carter found it in 1922. When the later workers were building the tomb for Ramses VI, they built their huts directly over the entrance to Tut’s tomb. They effectively buried the entrance under tons of limestone chips and ancient construction trash. If you look at a cross-section map, you see the massive Ramses corridor soaring above, while Tut’s tiny four-room suite sits safely ignored below.

It’s a miracle of accidental preservation.

Why the Rock Matters

The geology of the Valley is crumbly. It’s Esna shale and limestone. This sounds boring until you realize that water is the Valley's biggest enemy. When it rains in Luxor—which is rare but violent—the wadi acts like a funnel. Flash floods have turned these tombs into muddy swimming pools more than once in the last 3,000 years.

A good map today doesn't just show where the tombs are; it shows the flood protection walls. If you see a map with weird zig-zagging lines outside the tomb entrances, those are modern diversions. Without them, the vibrant paintings in tombs like KV17 would have been washed away decades ago.

Reading the Map Like a Pro

If you’re standing in the Valley, don't just follow the crowd to the three tombs open on your ticket. Look at the map at the visitor center—the big 3D model. Note the height of the mountain above you. It’s called al-Qurn, "The Horn." It looks like a natural pyramid. That’s why the kings chose this spot. They didn't need to build pyramids anymore; nature had provided a giant one for them.

🔗 Read more: Ilum Experience Home: What Most People Get Wrong About Staying in Palermo Hollywood

- KV5: This is the massive one. For years, people thought it was a small, unimportant pit. Then Kent Weeks started digging in the 1990s and realized it was a sprawling complex for the sons of Ramses II. It has over 120 rooms. On a standard tourist map, it looks like a dot. On a real map, it looks like a sprawling underground palace.

- The Axis Shift: Notice how earlier tombs (18th Dynasty) have a "bent" axis. They turn. Later tombs (19th and 20th Dynasty) are straight as an arrow. This wasn't just a style choice; it was about the sun's rays symbolically reaching the sarcophagus.

- The Unfinished Ones: Some of the most interesting spots on the map are the ones that lead to nowhere. KV19 was meant for a prince who became Ramses IX, so they just stopped working on his prince-tomb. It's basically just a very fancy hallway.

Practical Steps for Your Visit

Don't just walk in blind. The Valley is overwhelming. The heat is literal. 110 degrees is a "nice day" in the summer.

- Download the Theban Mapping Project plans before you go. They are the gold standard. They show the "isometric" view—meaning you see the depth, not just the floor plan.

- Pick your "big three." Your standard ticket usually allows entry to three tombs (not counting Tutankhamun, Seti I, or Nefertari in the separate Valley of the Queens). Use the map to find tombs that are far apart. If you visit three tombs right next to each other, you’re seeing the same rock quality and often the same artistic style. Mix it up. Go to KV8 (Merenptah) for the sheer scale, and then KV6 (Ramses IX) for the color.

- Look for the "Graffiti." It sounds weird, but ancient Greek and Roman "tourists" left their names on the walls of the tombs that were open in antiquity (like KV1). They are marked on some academic maps as "historical graffiti." It’s a trip to see a 2,000-year-old "I was here" note.

- Check the rotation. The Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities rotates which tombs are open to prevent humidity damage from tourist breath (yes, your breath kills the paint). Check the current "Open Tombs" list on the morning of your visit, as it changes without much warning.

The map of the Valley of the Kings is a living document. Even in 2026, we’re still finding new things. A few years ago, KV63 and KV64 were identified—not necessarily royal burials, but embalming caches and burials for singers. The map isn't finished. It probably never will be.

When you stand in the center of the Valley, look down at the gravel. You’re standing on top of history that hasn't been mapped yet. There are likely dozens of smaller pits and maybe even one or two significant royal burials still hiding under the debris of centuries. The map you hold is just the best guess we have so far.

Go early. Bring more water than you think you need. And remember that "down" is the most important direction on any map in this desert.

Next Steps for the History-Minded Traveler:

To truly grasp the scale, compare a plan of the Great Pyramid with the blueprint of KV17 (Seti I). While the pyramid is an outward monument, the Valley tombs are "negative architecture"—the art of what was removed. Before your trip, cross-reference the current open-tomb list with the Theban Mapping Project’s 3D flythroughs to decide which architectural styles (Bent vs. Straight axis) you want to prioritize seeing in person.